Some information may be outdated.

Science Moab talks with Joel Pederson, geomorphology professor and department head at Utah State University

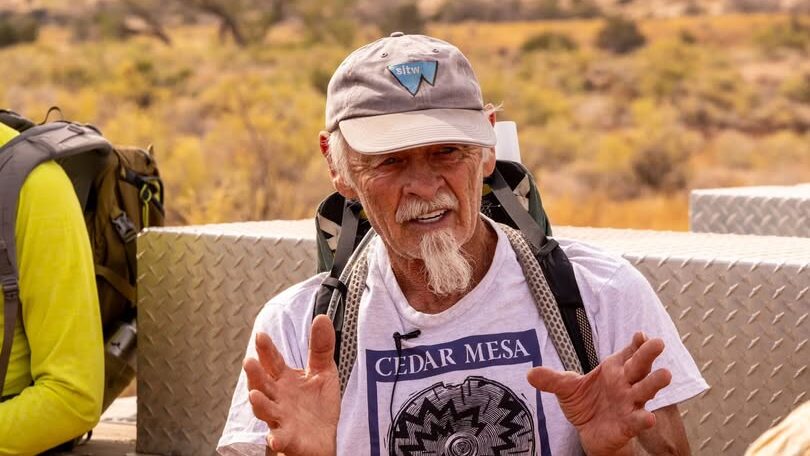

The term “river incision” describes the erosive power of a river carving narrow canyons or gorges and lowering the bed level of the waterway. Joel Pederson, a geomorphology professor and department head at Utah State University, is studying incision rates of the Colorado River—and he estimates the fastest rate of incision in the river is occurring in the Moab area.

Science Moab chatted with him about his research.

Science Moab: Why is the Colorado River experiencing its fastest incision rate near Moab?

Pederson: I think we can show that the reason why erosion is so fast in southeastern Utah is because that’s sort of where the wave of incision is now hitting, as erosion progresses upstream from the edges of the Colorado Plateau.

The rocks in southeastern Utah and the Canyonlands district are also less resistant—they’re weaker sedimentary rocks than the rocks tend to be at the edges of the Colorado Plateau. For example, the Grand Canyon also has these layers of sedimentary rock, but a lot of them are really resistant limestones that make the cliffs. Then there’s the basement rocks down at the very bottom of the Grand Canyon. So this wave of incision is also hitting rocks that are really easy to erode: therefore, we’re seeing an amplified bullseye of incision in the Moab area.

Science Moab: Your latest research includes a lot of outcrop work just north of Moab around Dewey bridge. What new data have you come across?

Pederson: One of the many evolutions of our capabilities as geoscientists over the last couple of decades is in geochronology, the dating of geologic materials. Most of the research that my students and I do is really based on looking at old river deposits that record where the river used to be in the landscape in the past. We’ve been employing this dating technique called ‘luminescence dating’ to date the sand grains within the ancient river gravel deposits.

One thing that’s happened in the last five or ten years is that with technological advances, we can date older and older deposits with luminescence. Ten years ago, we were really limited to about the last 150,000 years of geologic history where we could use that technique and figure out the history of the river. In the last five years, we’ve started using feldspar instead of quartz. So it turns out feldspar as a mineral, ends up accumulating damage and holding it in a useful way over longer time periods. Now we’re able to start doing work where we can look back up to 700,000 years. That has really changed things.

Science Moab: What are some of the processes you and your team go through when you’re trying to study all these river deposits over such a large area?

Pederson: As we have gone from studying the Grand Canyon area, and working upstream into Meander Canyon, and then upstream of Moab, in each one of these places, one of the first things that my students do is just plain old map and document all of the river deposits that are found in that canyon landscape.

Then we survey the locations of all these things with GPS, and their exact heights and positions in the landscape. It is sort of a cool mission of discovery, because we get to go in and document and explore these river deposits at a different level. For me, that’s part of the fun—just to kind of get to see and document where these all are exactly. If we’re lucky enough, we find places where we can sample the sand and come up with the story of incision.

Science Moab: What is the next step in your research?

Pederson: One thing that I must make clear and admit is that it’s a working hypothesis. There’s still going to be a multi-year process of really testing that hypothesis with the data. As you go from Moab upstream, if there is this wave of incision, one pattern we should see is that over recent geologic time, the incision rate should get faster and faster and faster the closer you get to the front of that wave. Then if you go upstream even farther, that rate would suddenly get really slow, because the wave hasn’t gotten there yet.

This is a really good hypothesis; it’s just not tested yet. We have one main study area, which is up between Dewey Bridge up towards Westwater Canyon. Once we have the deposits mapped out there, we’ll be able to say what happened.

Science Moab is a nonprofit dedicated to engaging community members and visitors with the science happening in Southeast Utah and the Colorado Plateau. To learn more and listen to the rest of this interview, visit www.sciencemoab.org/radio.

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.