Some information may be outdated.

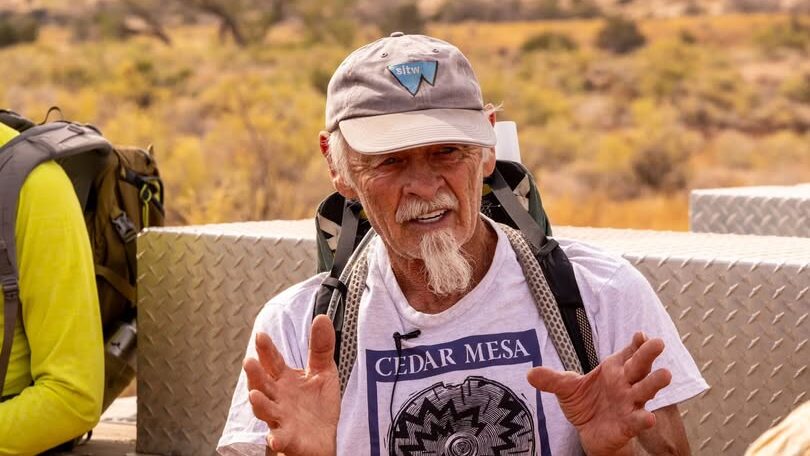

As wolves migrate out of the Yellowstone reintroduction area, their numbers are expanding to the north and south—including into Utah, where they once roamed. This week, Science Moab talked with Kirk Robinson, founder and executive director of Western Wildlife Conservancy, about what wolves are doing, the ecosystems they live in, and what it might mean to have wolves back on the Western Slope.

Science Moab: Did wolves live in Utah? If so, where were they located?

Robinson: Yes, there were gray wolves in Utah, wherever there was suitable habitat. Wolves lived in the Abajos, La Sals, Book Cliffs, and parts of the Uintas and Wasatch. But they were not an enormous size—my pet dog weighs 100 pounds, and that’s the average size of the male wolves. The females are 80 to 85 pounds. So they’re big animals, but not huge. They are effective predators while pack hunting, but they are not giants, and they’re not out to eat anything they can find.

Utah, like other states, tried to eradicate wolves in the ‘30s and ‘40s. Now, there are no known wolves in Utah; though there have been wolves coming through Utah, they just don’t stay here. They disperse from Yellowstone country and go through the Uintas and Book Cliffs and into Colorado. That’s about to change, and that’s the reason I want to talk about wolves. The landscape for wolves has changed in a significant way. I think Utah citizens really need to know about it and are probably going to be very interested in learning about it.

Science Moab: Where are wolves entering Utah from today?

Robinson: Wolves, especially males, when they reach about a year or two of age, go out on their own and find a habitat where they can survive. That includes finding a mate, and they form their own wolf families. A number of wolves have come into northern Utah, and wolves have made it from Yellowstone country into northern Colorado. A breeding pair has established itself in North Park in Colorado and had pups. That’s the first known naturally established pack in Colorado since the reintroduction. Maybe more significantly, Colorado citizens passed Proposition 114 in the fall of 2020, mandating that Parks and Wildlife reintroduce gray wolves to the Western Slope of Colorado by the end of 2023. They will probably reintroduce anywhere from about 35 to 55 wolves. The question is: where they are going to get these wolves? Are they going to just reintroduce wolves from Montana or Wyoming, or are they going to reintroduce Mexican gray wolves?

Science Moab: What are the wolves eating, and what impact does that have on the ecosystems they live in?

Robinson: Well, they’re apex predators. They’re at the top of the food chain, and nothing else really preys on them. So they play a special role because of that. They eat mainly older elk that don’t contribute too much to reproduction, because they’re slower and sometimes sickly. The carcasses of the animals the wolves prey on are food for other animals as well, including eagles, wolverines, beetles, and grizzly bears. Bears might come along and take a carcass away from the wolves, especially when they’re coming out of hibernation, so it’s an important food source for them. To some extent, wolves also eat deer. But gophers and mice and things like that really don’t have enough calories to make it worthwhile. Elk are the main source of food in Yellowstone for wolves.

Science Moab: Can you speak to the current management elements of reintroducing wolves to the area?

Robinson: We don’t know yet what management regime Colorado will approve, or whether it will allow sport hunting of wolves, but wolves are going to proliferate and come to Utah. It’s the gray wolves reintroduced to Colorado that most concern us in Utah, but also the Mexican gray wolf. When the first recovery plan was developed for the great Mexican gray wolf, the recommendation of a team of expert scientists was that there be three recovery areas, each with a minimum population of 200 wolves, and an overall population of at least 750 wolves. Utah and Colorado got together and decided they didn’t want any Mexican wolves straying north of I-40 or coming into Utah. The Fish and Wildlife Service ended up catering to the states. That doesn’t mean wolves can’t leave Arizona and New Mexico and go north. If they don’t get caught, they could end up in Utah or Colorado.

The problem is partly the restricted geography the wolves would be confined to, but also these animals stem from just seven founders, so they’re tremendously inbred. Although the Mexican wolf population has grown rather significantly in the last five years, I don’t think it’s gonna go anywhere near 750. It’s about 200 right now, and I’d be surprised if it’s not close to topping out. So if Colorado decides that they would like some Mexican wolves in the San Juan Mountains, then we will have another population of Mexican wolves. And the Endangered Species Act allows the Fish and Wildlife Service to put them into a suitable habitat for recovery to occur, even if it was not historic habitat.

Science Moab: What questions are yet to be answered surrounding the reintroduction of wolves?

Robinson: If we allow them to proliferate a bit, and we have a few packs in the Book Cliffs, what will that mean? Will it mean that cattle are in danger? Will it mean that deer and elk populations will plummet? There may be somewhat greater mortality to deer and elk—the wolves will also cause these animals to move around more and be more cautious. That’ll make some changes in the natural foliage regime and might make it more difficult for people to hunt deer and elk. But how many deer and elk belong exclusively to hunters, and how many of them belong to the ecosystem?

Science Moab is a nonprofit dedicated to engaging community members and visitors with the science happening in Southeast Utah and the Colorado Plateau. To learn more and listen to the rest of this interview, visit www.sciencemoab.org/radio. This interview has been edited for clarity.

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.