Some information may be outdated.

Walking along the Grandstaff Canyon trail today, it is easy to understand why early Moab settler William Grandstaff chose the lush canyon as a place to settle. The ever-flowing stream, lined with cottonwoods and dense vegetation, is a veritable oasis: a shady, cool haven in an often harsh and arid landscape.

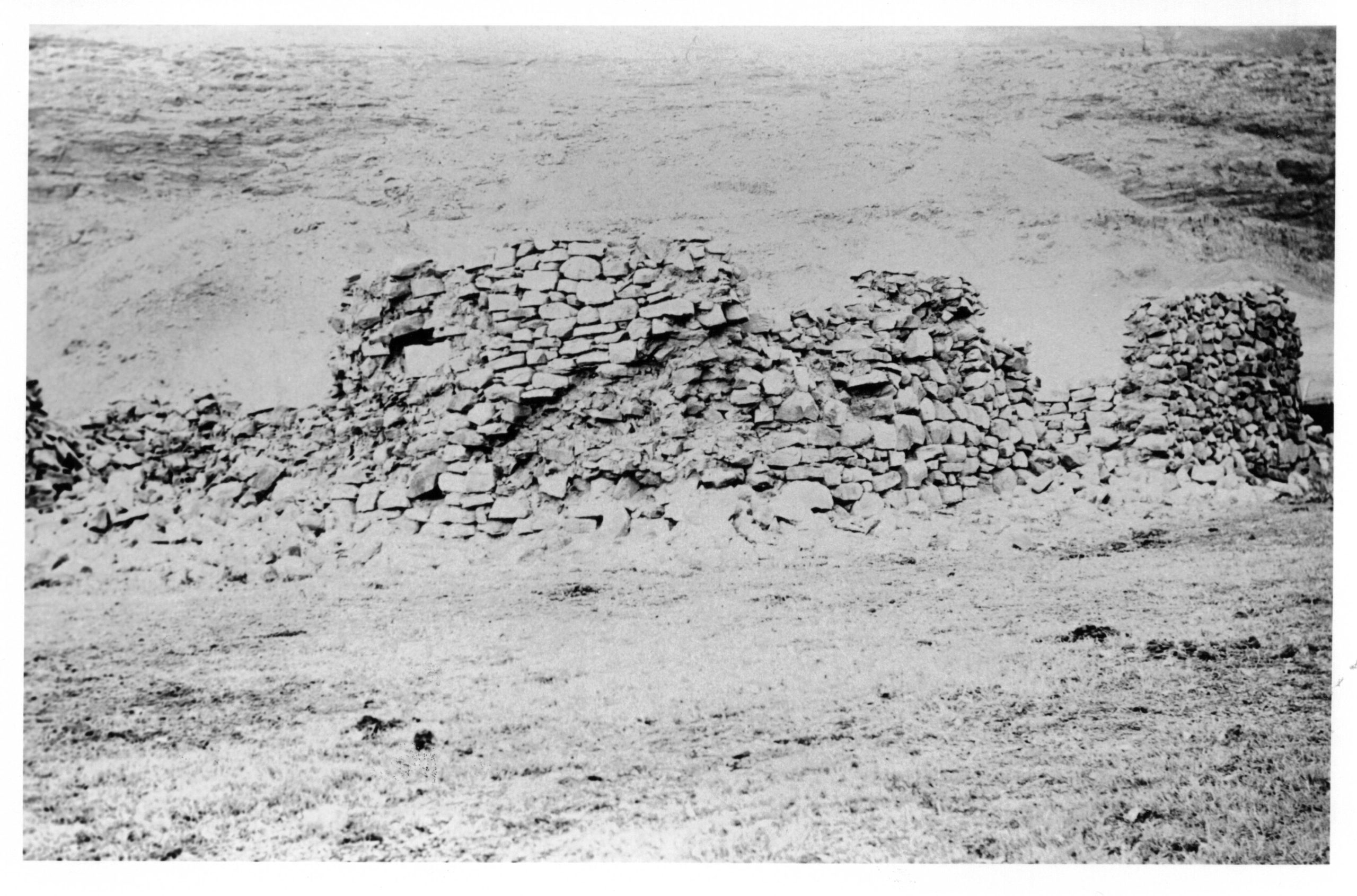

When Black frontiersman William Grandstaff arrived in the Moab Valley around 1877, there was no Moab. He briefly occupied the abandoned Elk Mountain Mission fort along with a Canadian fur trapper nicknamed “Frenchie.” The Mission, established in 1855, was a short-lived attempt by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints to colonize the Moab Valley, which failed after a few months due to violent conflict between missionaries and the local Ute people. Later settlers reported noticing a small garden at the fort, suggesting that Grandstaff and Frenchie had grown food there.

Grandstaff was one of the very first non-Native residents to settle in this region, which began to see settlement by prospectors, frontiersmen, and explorers of all sorts who were venturing west in the 1880s.

After living in the mission’s remains and then allegedly in a building that he constructed at what is now Moab Springs Guest Ranch, Grandstaff ran cattle in the canyon that now bears his name. Grandstaff’s canyon was one of the few in the Moab area that had year-round running water, making it highly desirable “real estate” at a time when the region began to see an influx of cattle ranchers and settlers vying for water and food for their stock.

A painting recently donated to the Museum by the City of Moab is thought to depict William Grandstaff during his time in Moab. The painting, by Otho Murphy, shows a solitary figure carrying a deer, apparently returning to the abandoned Elk Mountain Mission fort from a hunt. A covered wagon drawn by oxen appears in the distance, representing the arrival of other settlers to the Moab Valley.

Grandstaff’s time in Utah was brief: He reportedly fled Moab in a hurry in 1881 when tensions between white settlers and local Native Americans (presumably the Ute) were turning violent. Rumors circulated that Grandstaff had supplied the Native Americans with alcohol, which angered the settlers, though the truth of these allegations and the backlash Grandstaff faced are hard to substantiate. Grandstaff purportedly left Moab so quickly that he left behind his cattle.

These Century-and-a-half-old rumors are impossible to either refute or substantiate, and what we know about Grandstaff leaves much room for imagination. What was life in early Moab like for Grandstaff? What were his day-to-day interactions like, as a Black rancher following the tumultuous and painful years of the Civil War and Reconstruction? How might his race have factored into the reputation and stories that accompany his legacy in Grand County? How might interpreting Grandstaff’s history impact the Moab community today?

This is the third part of a four-part series highlighting genealogical research conducted about Moab settler and Black frontiersman William Grandstaff. The Moab Museum is dedicated to sharing stories of the natural and human history of the Moab area. To explore more of Moab’s stories and artifacts, find out about upcoming programs, and become a Member, visit www.moabmuseum.org.

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.