Chris Johnson, a firefighter and EMT with the Rock Creek Fire District in Kimberly, Idaho, stood at the edge of a sandstone cliff near Moab, contemplating the vertical drop. He was harnessed into a rope swing, helmeted, and surrounded by guide staff and new friends, participating in a weekend retreat for veterans and first responders who are processing trauma or dealing with other mental health issues. Johnson remembers thinking as he looked over the edge, “This isn’t you—this is a perfectly good rock, why would I jump off it?”

Video of the moment shows him puffing out a series of quick exhales while a few voices offer encouragement in the background. Then someone starts a countdown from five. Johnson lets out an expletive under his breath and starts moving, shuffling to the very edge of the rock until he’s in space.

“I joke that I’d probably still be standing there today if the guys hadn’t counted me down,” Johnson said.

He filmed his swing with a GoPro. He sails through space, his whoops audible under the crackle of the wind. When he slows down, he tells the camera, “You did it! …You’re a strong individual. You stepped out of your comfort zone, dog. Did something you would have never done before.”

Johnson said the experience was pivotal—it dispersed a cloud that had been darkening his outlook on life.

22 Jumps

The retreat is organized by a nonprofit called 22 Jumps, founded by Marine Corps veteran Tristan Wimmer. Wimmer’s brother, Kiernan Wimmer, who was also a Marine, suffered a traumatic brain injury in 2006 during combat operations in Iraq. Though he recovered, the injury left him with ongoing mental distress, and he took his own life in 2015.

“When my brother died, I was working overseas in Afghanistan when I got the call,” Tristan said. “I was a wreck, I was a complete wreck. It took me a few years to figure out how I wanted to honor him.”

Tristan and Kiernan had shared a love of BASE jumping, and in 2020 Tristan decided he would do 22 jumps in a single day—the estimated number of veterans who died by suicide each day in 2010, according to a 2012 Department of Veterans Affairs report. (The report notes that the estimate “should be interpreted with caution”.)

Wimmer hoped to raise $2,200 to donate to research on traumatic brain injury. He raised about $25,000 through a combination of donations from businesses and individuals.

He raised even more money doing the same event the following year, and in 2022 decided to formally establish the nonprofit, which now holds annual BASE jumping fundraising events in Phoenix, Arizona, Twin Falls, Idaho and New River Gorge National Park in West Virginia. Over the last five years, 22 Jumps has raised over $400,000 to support research on TBI.

The retreat

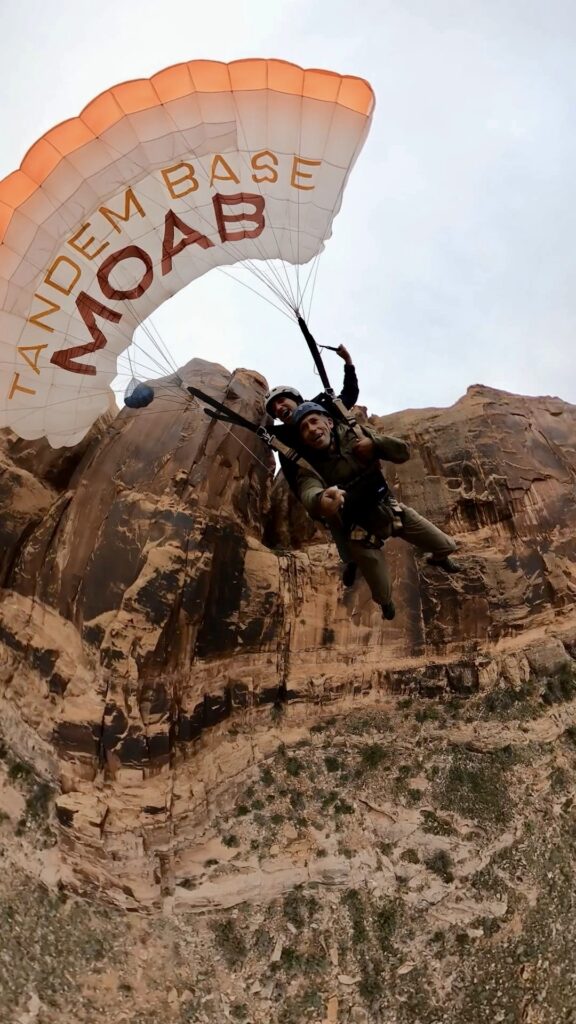

Moab local Matt LaJeunesse owns Tandem BASE Moab, a BASE jumping guide company, and is also active in fundraising events to support local first responders. He knew about 22 Jumps, and had the idea of hosting a multiday retreat in Moab for veterans and first responders, especially those who might be dealing with trauma or mental health challenges. He reached out to Wimmer and to Moab guides and outfitters, and the first retreat came together in 2023 over Veterans Day weekend.

This year’s four-day retreat was another success; participants packed in adventure sports, including BASE jumping, skydiving, a helicopter flight, a rope swing, mountain biking, and rock crawling in Jeeps. Last year participants also tried highlining with Moab’s Elevate Outdoors guide company.

Many Moab businesses donated services and/or offered discounts to the retreat, including Chile Pepper Bike Shop, Skydive Moab, Twisted Jeep, Voodoo Air, helicopter pilot Rus Robinson, Rim Cyclery, Mindful Somatics for a breathwork session, Tandem BASE Moab, Cactus Jacks, Doughbird, and the Moab RV and Glamping park.

“It’s pretty remarkable, the amount of generosity that makes these events possible,” Wimmer said.

The retreat is capped at about a dozen participants, usually recruited from the 22 Jumps informal network. Wimmer said they look for people who could really benefit from the retreat—people who might not otherwise have experience with or access to adventure sports, and who might need the camaraderie, challenges, thrills and perspective the retreat can generate.

Johnson was recommended to the retreat by a close friend. He had recently been through a 40-day in-patient recovery program, and while the experience got him sober and gave him insights about his own emotions and tools to cope with them, he still felt a weight after going home—a sense of shame and regret.

On the 7 hour drive from Idaho to Moab, Johnson had lots of time to weigh his decision to participate in the retreat—to jump off cliffs and out of planes, acknowledge his mental health struggles to strangers—and he considered turning around. But he didn’t. He overcame initial nervousness to become fast friends with the other participants, and was able to open up about his experiences. He talked with another first responder on the retreat about going through recovery, trusting that his new friend would understand and wouldn’t judge him. The breakthrough moment with the rope swing made him feel like a new person.

“It’s been a breath of fresh air,” Johnson said of the whole experience.

Adventure sport therapy

At the end of the retreat, Wimmer hosts a feedback session that allows participants to share their thoughts on the weekend and debrief. It’s also a chance to gather qualitative data on how extreme sports may be therapeutic for people with depression, anxiety, or post-traumatic stress disorder. Some research has been done on the concept; Wimmer hopes data from these retreats can be useful and potentially inform a larger study exploring the idea.

Anecdotally, participants in the retreat do find the experience uplifting and meaningful. In a video about the retreat posted on the 22 Jumps website, the organization’s chief medical officer, Jon Syzlobryt, talks about the benefits of extreme sports. He says the feeling just before a BASE jump is the closest thing he’s felt to what he felt during military combat—and that’s a good thing.

“It’s important to not live on adventure sports,” Syzlobryt says in the video, “but the perspective gained from them, for me, has been super therapeutic.”

“When you are inundated with adventure sports, you forget how therapeutic it is,” Wimmer said. That’s one reason 22 Jumps looks for people who aren’t already immersed in the adventure sport world. But, he added, that world is still a strong support system, even when it’s become familiar.

“Novelty definitely adds to the experience,” he acknowledged. “But it’s the skill-building and the community-building… That’s what brings people back. Not necessarily the ‘woohoos,’ but being around other like-minded people doing hard things and finding a way to be your full self.”

Johnson said the retreat was “epic, to say the least.” He’s taken up mountain biking at home, a sport he didn’t do before the 22 Jumps retreat. He wants to return to Moab with his wife and sons, just to experience the beauty of the landscape again—and maybe skydive again.

![Santa at City Market [2024]](https://moabsunnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_0052.jpeg)