Some information may be outdated.

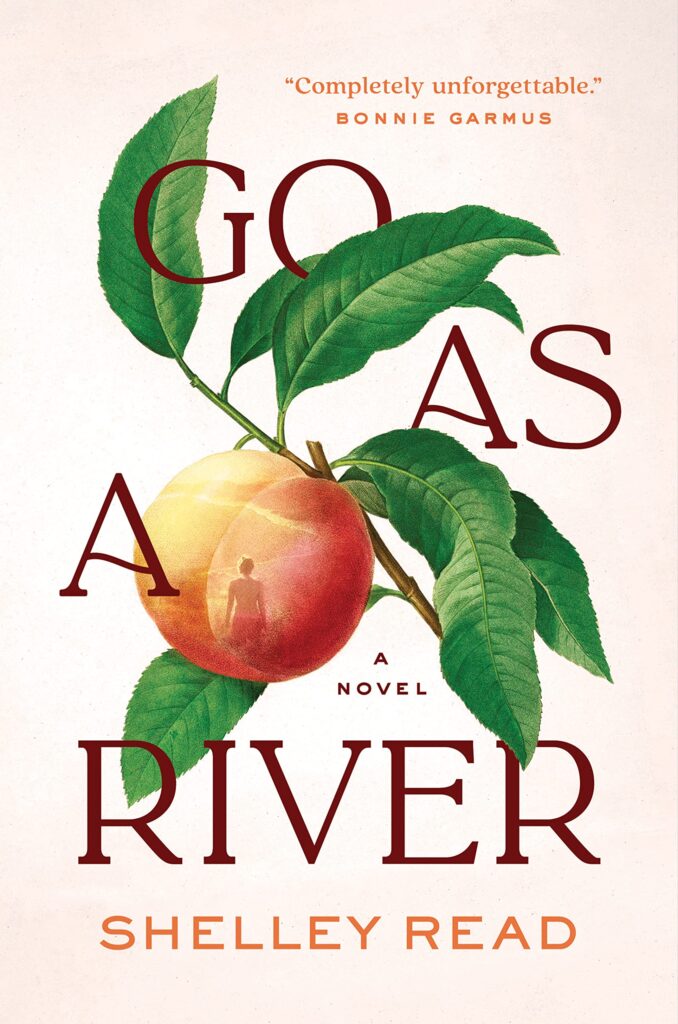

Shelley Read is a writer, teacher, journalist, and now, a novelist: “Go as a River,” her debut novel, was published at the end of February.

The book, a historical fiction, follows the life of Victoria Nash, a teenager in the 1940s who runs her family’s peach farm in Iola, Colorado. Those who know the true history of Iola know that Victoria’s story is has a dark tone—the town of Iola was evacuated and flooded in the 1960s to make way for Blue Mesa Reservoir—but the novel follows its main character over the course of decades, following her as she flees her teenage life to live in the harsh wilderness. During the course of her life, Victoria finds the meaning of love, loss, and home.

The book already has fantastic reviews; it will also be translated into 30 languages and published in 34 countries. Read’s book tour is taking her all over the West, including through Moab: on Tuesday, March 21, Back of Beyond Books will host Read at 7 p.m. for a book reading and signing.

The Moab Sun News chatted with Read about her career, inspiration, and her novel.

MSN: When did you know you wanted to pursue a writing career?

Read: The answer is kind of convoluted, because I always knew I wanted to be a writer. As a little kid, I wrote a lot. I wrote stories and poems, and I just always thought in story. In third grade, we had an assignment to write a two-page story, and I wrote a 66-page book.

I went to the University of Denver and double majored in journalism and creative writing; then I got a Master’s degree from Temple University’s graduate program in creative writing. I was well on my way, and knew that’s what I wanted to do with my life—but then I was awarded a teaching fellowship during my Master’s program, and I realized I also really love teaching. I took a detour, and I ended up teaching for 30 years.

I still wrote here and there, but I was a full-time professor and I raised two kids, so I went many, many years where writing was just an aside. I’m coming back around to it now in my mid-50s, and it’s really like I’m returning to where I intended to go in the first place.

MSN: Landscapes can very easily influence art and creativity—what writing and creative inspiration do you draw from living on the Western Slope?

Read: Everything. I always say I’m the happiest when I’m on the highest of high mountain peaks, and in the deepest of deep canyons—extremes are where I find my greatest joy. I spend a tremendous amount of my life in wild places, and I honestly think wild landscapes are the only places where existence really makes sense to me. When I go out, I always have a journal so I can write my observations of the natural world.

I’m a fifth-generation Coloradan, and so my sense of place is rooted very deeply in my soul. I’ve spent my entire adult life in the Gunnison Valley, so it is very much my homeland—this sense of place really defines who I am.

So I knew what I wrote in this novel was going to be deeply rooted in place. And that’s also why it also became deeply rooted in displacement. I am so attached to my homeland, so I really started imagining what it must have been like for the people of Iola to be displaced from the generational homeland that they loved.

And then along with that, of course, I couldn’t write a narrative about displacement in the American West without also including the Indigenous experience, because before the ranchers and farmers were displaced in the Iola area, there was the very violent and tragic displacement of the Ute people and the Indigenous people of the area. I tried to deal with Indigenous displacement incredibly sensitively and respectfully out of deep compassion for what they went through.

There are many layers of place and displacement in the book, because those things really matter to me.

MSN: How did your novel come together?

Read: In my graduate program, I mostly wrote short fiction—I never really thought about being a novelist, to be honest. But well past graduate school, the nugget of this story—the character Victoria—started forming in my mind. And then my imagination took her to the town of Iola, and I started linking her to the very real facts of the drowning of Iola during the creation of the Blue Mesa Reservoir. The way I like to phrase it is, I really didn’t have time to write this book. But it was just a story that insisted on being told.

My process was very come and go—I would write it a little bit here, a little bit there, and sometimes I wouldn’t even look at it for months at a time when I was really busy with other things. But I couldn’t kick it. It just stayed with me. And at some point, I had enough notes, and enough plotline and whatnot, I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, I think this is a novel—I don’t know how to write a novel!’

But I just kept chipping away at it. And once I felt like it was fairly done, I made many revisions—I really played with the structure. I always taught my creative writing students that all writing is process, process process process, and you have to be really generous with yourself around that process.

And boy, I really took that to the hilt in the process of writing this book. Not only did I chip away at it little by little over time, I then revised many, many, times before I knew that it was really where it needed to be.

MSN: Why did you want to tell this story through the character of Victoria Nash? How does her life shape the meaning of the book?

Read: The character of Victoria came first with this book. There’s a scene about 100 or so pages into the book when Victoria is sitting in a meadow after she fled into the wilderness, and a mother doe comes shuffling out of the foliage followed by two little fawns.

That exact scene happened to me one evening when I was out camping alone—I see deer and wildlife all the time, but there was something about that moment. I was sitting there and I connected eyes with this mother doe: I was a mother and she was a mother and I just kept thinking, ‘How are you going to keep those two babies alive?’ I grabbed my journal and wrote the scene down, and later I started thinking about that scene through the lens of someone who is not myself. And that’s when Victoria was created.

From the beginning, the main character of this book was going to be someone who is digging into what it means to be a woman in the world. I knew the book would have something to do with motherhood, but I also knew it was going to have something to do with cultural limitations on women—how women are often defined by structures outside of themselves, especially in the 1940s.

But I also always knew that Victoria was far stronger than she thought. The trajectory of the novel has to do with wild landscapes and the flooding of Iola, but more than anything it follows the way in which Victoria discovers her own strength and resilience in the myriad challenges she faces. The wild landscape teaches her a lot about her strength, just like the wild landscape has taught me a lot about my strength.

MSN: Were there any other parallel moments like that?

Read: Not so much—nothing in the book is strictly autobiographical. The themes are things I obsess over a little bit philosophically: these themes of displacement, where we turn when home and family are lost, and the natural world.

I also drew on my Colorado heritage—my family, my ancestors, were ranchers and farmers on the eastern plains of Colorado. Here in the Gunnison Valley, I’m surrounded by people who have generationally loved and worked this land. I’m fascinated by them because they’re strong as hell, and I’ve observed them my whole life.

The things that I funneled into this book were my understanding of the natural landscapes and these thematic concerns, and then also the tenacity, the humility, and the toughness of the ranching community that I’ve learned and observed over time.

In writing “Go as a River,” I did research on specific details around the building of Blue Mesa Reservoir, and I also did a lot of research on how to grow peaches. But other than that, I didn’t have to do as much research as you might think, because I knew these landscapes and these people so well. That was a great joy actually, and it helped me create authentic characters.

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.