Some information may be outdated.

Every Sunday afternoon, Herman Herrera’s plum-colored 1949 Oldsmobile is parked outside the KZMU community radio station, and Herrera can be found inside broadcasting his weekly show, Entre Las Piedras.

“It’s Bluebird, el pájaro sin alas,” he greets listeners on the air. “¡Quédate con nosotros hasta las cinco de la tarde para la música!”

The show is a mix of styles and artists from all over, including Puerto Rico, Colombia, Spain, Mexico, California, and especially, New Mexico, where Herrera is from. He plays mariachi, contemporary, romantic, rap—he mentioned artists from Puerto Rico like Luis Fonsi and Daddy Yankee.

“I love music in general,” Herrera said.

He switches between Spanish and English when talking to listeners in between songs—he uses both because he wants his show to be for everyone. If someone tuned in and heard only a language unfamiliar to them, he said,

“You would turn a deaf ear to it.” But he still wants the show to flow, so he doesn’t get bogged down by repeating everything in each language.

“I try not to translate,” he said. “I speak Spanish, then English, and hope that it all comes together when it comes out on the airwaves.”

Herrera is also a musician himself. He sings and plays the guitar, and used to gather with other Moab musicians to jam at the Outlaw Bar, which used to be in the building that later became Frankie D’s, which has now closed. He sometimes plays for churches as well. He’s recorded two albums: The first was initially released only on cassette, in 1995. He later had it produced on CD. The second was made in 2000. Most of the songs on his albums he wrote himself.

“They’re not about anyone or anything in particular, but just love songs,” he said. The CD’s aren’t kept in stock at any retail locations, but if you’re interested, you can get in touch with Herrera through KZMU to obtain a copy.

Herrera has lived in Moab for 18 years, moving from Española, New Mexico in 2003 to spend time with his father, who lived in Moab at that time and was terminally ill. He enjoyed spending time with his father, fishing and being outdoors, and ended up meeting his wife and staying in Moab. Herrera has been a volunteer DJ at KZMU for over 10 years. Before moving to Moab, he had a paid gig for nine years as a part-time DJ for the radio station KDCE in Española, with a show called “In the Mix.” More people phoned into the radio station there, he said, which was nice—it let him know that people were listening. Moabites don’t call in to his show very much, but when they see him around town they often greet him by his DJ name and say they enjoy listening.

“Lots of people say, ‘Hey, you’re the Bluebird! We listen to your show every Sunday!” Herrera said. He chose the DJ name “Bluebird” in honor of the Blue Bird brand buses that bands used to travel in when touring—“pájaros sin alas,” or birds without wings.

It’s fitting that Herrera’s DJ name comes from the intersection of music and another of his interests, which is vintage cars. He owned a radiator shop in Española for 20 years, and was also the president of the low-riders club there. He owned a ‘37 Chevy that he’d fixed up and modified to be a low-rider. He lost the car in a card game—the last time he ever gambled, he said.

He bought his current Oldsmobile from another vintage car enthusiast in town, after admiring it for some time. He drives it to the radio station every Sunday to keep it in good order. Herrera’s son, Tyler, is a student at Grand County High School and will soon be taking an advanced auto-shop class, and plans to bring the Oldsmobile, which is built on the chassis of a 1980s Crown Royal, into class to tinker on. Tyler is also learning to play the guitar, and likes to jam with friends.

Herrera has seven other adult children: His daughters Misty Herrera, Joní Herrera, and Heather Anderson live in New Mexico. Misty is a technician in an auto mechanic shop, and Joní and Anderson are both in the medical field. Herrera’s stepdaughter Deandra Billie lives in Moab with her two children, and his stepdaughters Cassandra Joe and Sandra Billie, who has two children, and stepson Jeremy Billie live throughout the west.

In Española, Herrera’s schedule was more flexible because he owned his own shop. He could practice music with friends during slow hours and leave the shop for a few hours to do his radio show.

“It was pretty crowded,” he said of his old radiator shop. “A lot of people came to visit.” He now works for the Community Recycle Center. He likes that he’s helping to take care of the environment through that work, though his hours aren’t as flexible as they were when he owned his own business.

Meanwhile, he keeps up with another of his quasi-professional hobbies: woodcarving. Herrera carves wooden sculptures, many of human faces or figures, and has sold them at art fairs and displayed them at galleries. He sometimes uses branches or logs to create his pieces, often letting the shape of the natural wood guide the final sculpture. In a piece called “Man Without a Cross,” for example, the shape of the branch he began with suggested the form of outstretched arms and a bowed head.

For other pieces, he starts with dimensional lumber. In a series called “Earth People,” he carves faces out of pressure-treated 4×4. He uses a dremel, chisels, and sandpaper to shape the wood, and may spend several days on one section of a sculpture.

“I always attribute the wood carving to my ancestors,” Herrera said, remembering how his great uncles would bring logs to the yard and mill them into lumber to make furniture. His younger uncles, he said, would carve small horse figures or saddles out of wood.

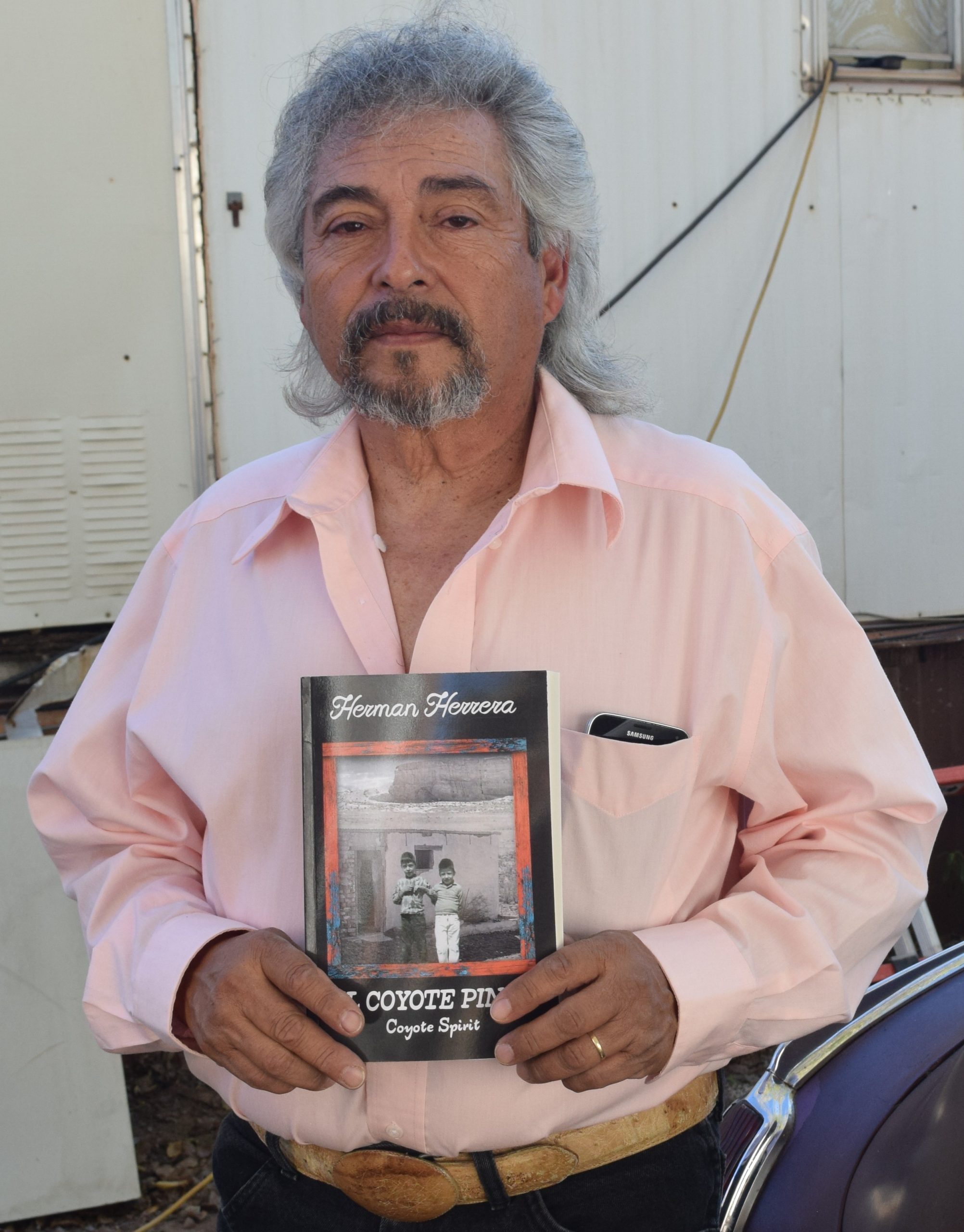

Herrera treasures memories of his family and his childhood, and this summer, he self-published a book of his stories and impressions from growing up in the mountains of New Mexico. He started writing in the 1990s, he said, with no plans or intentions of creating a formal published work. In the last couple of years, though, he heard an advertisement on the radio from Page Publishing, a self-publishing company through which authors can have their work professionally edited, bound, and distributed. He submitted his book and it is now available at Back of Beyond Books in downtown Moab, at other bookstores including Barnes and Noble, or through online retailers like Amazon or Ingram.

The book is called El Coyote Pinto, and is written from the perspective of Herrera as a little boy: “El Pequeñito.” Herrera says he has memories from as young as 3 years old.

“They’re all pretty much happy memories, so I don’t block them,” he said. “I let them flow.” He remembers how family and neighbors used horses, buggies, and wagons in the mountainous area where he grew up, because it was hard at that time to adjust cars to run well at altitude. His family grew wheat and brought the harvested crop to a processor, where the grain was separated from the straw by a machine powered by a belt threaded onto a Model-T Ford that sat up on blocks. The family grew most of the food they needed, buying only salt, coffee, and sometimes sugar.

“For me, it’s just amazing,” Herrera said of publishing the book. “I feel like I want to tell everybody.”

Even when he’s paying a bill over the phone, Herrera said, when the customer service agent asks at the end of the call, “Is there anything else I can help you with?”—he’ll mention the book. He’s personally sold over 100 copies himself, and he said Back of Beyond recently told him they are out of copies and ready to order more.

Herrera loves creating and said he has enough plans to occupy all his time once he reaches retirement.

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.