Some information may be outdated.

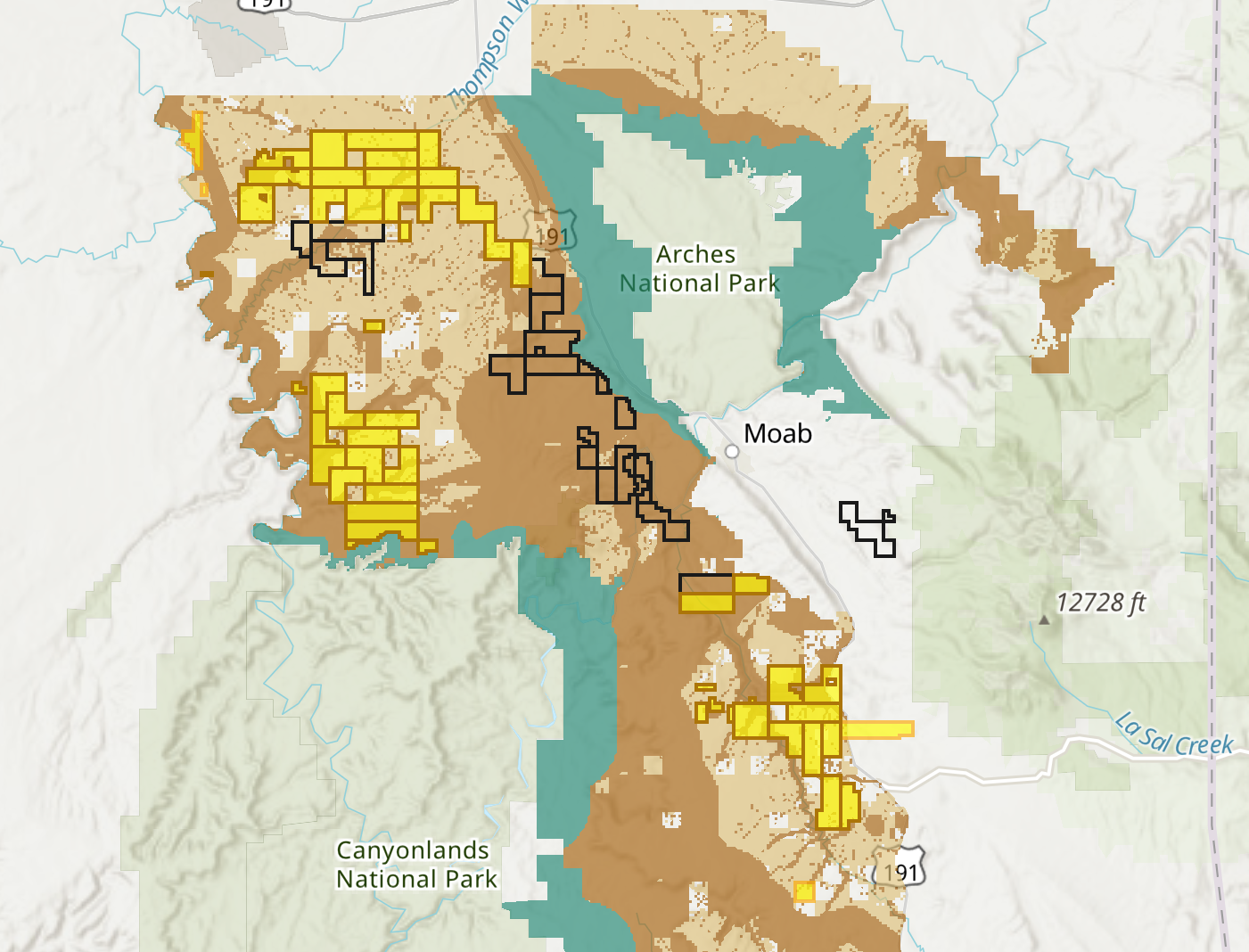

The Utah Bureau of Land Management’s September quarterly lease sale has raised concerns among public lands watchdogs and local elected officials in the Moab area. Forty-nine parcels containing 82,010 acres in the Moab/Monticello BLM Field Office area will be offered for sale, many in locations that could set the stage for a conflict between energy development and prized recreation areas as well as protected natural areas.

“The implications could be huge,” said Jason Keith, managing director for Public Land Solutions, a local nonprofit that advocates for recreation on public lands.

The City of Moab is engaged with the BLM as a leasing program partner. Meanwhile advocacy groups have been monitoring the sale process and, early on, expressed concern at the vast acreage of nominated parcels.

Red flags

The public comment period on the sale opened on June 9 and revealed that the BLM did not make available all parcels in which interest had been expressed.

About 20 parcels, most of them close to the City of Moab and Arches National Park, were nominated but not included in the sale list.

“They nominated for leasing every parcel that’s not already leased,” under the Moab Area Master Leasing Plan, Keith said.

The Moab Master Leasing Plan, a BLM document published in 2016, defines what areas are available for oil and gas leasing, and any stipulations that apply to specific parcels. For example, some parcels may be available to extract underground resources, but don’t allow any surface development.

Stakeholders and advocacy groups, including the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, a nonprofit that advocates for wilderness, participated in the development of the plan.

Landon Newell, staff attorney for SUWA, said his organization and other groups didn’t foresee the Master Plan allowing for such expansive acreage to be offered at once, though the move isn’t specifically prohibited by the plan.

“It was never envisioned that the Master Leasing Plan would be weaponized like is being done here,” said Newell. “Never was it envisioned that BLM would essentially offer all of this land at one time.”

He cited the Trump administration’s “energy dominance policy” as the impetus for the BLM’s current approach.

“The unique situation that we have here is that under the Obama administration, for example, the BLM would oftentimes not move forward with lease nominations,” explained Newell. “They would get them and they would look at where they were located and they would realize that the land nominated for leasing served much better purposes: for example, recreation, or wildlife, or water quality.”

The energy dominance policy emphasizes energy developments as a priority among public land uses.

“The BLM has new guidance and directives that essentially require the BLM to offer nominated leases for sale for development,” said Newell, asserting that since the energy dominance policy was issued, the BLM rarely declines to make available parcels for which there’s been an expression of interest.

For the September 2020 sale, the BLM deferred 26 of 99 parcels on a statewide preliminary list for potential inclusion in the sale, reducing the possible statewide acreage from 152,125 to 114,050. The majority of proposed parcels remain on the sale.

“The agency is, in its view, essentially required to offer these leases for development,” Newell said.

The size of the sale and location of the parcels have advocates and local leaders nervous.

“They’re right next to a bunch of high-value recreation areas that drive the local economy,” said Keith of the nominated parcels.

Some of the parcels are less than a mile from scenic areas like Canyonlands National Park and Dead Horse Point State Park. Others are close to the White Wash Sand Dunes Recreation Area, a popular OHV recreation site, and the Monitor and Merrimac Buttes area, cherished by both mountain bikers and OHV users.

Moab’s city government had requested that it be named as a cooperating agency with the BLM as environmental assessments were conducted of the parcels within the expression of interest. The assessments, or EAs, are required before proposed parcels are confirmed to be included in the sale.

“The city’s interested in engaging in the environmental assessment so that those economic benefits [of oil and gas developments] are weighed against the recreation benefits to the community,” said Moab City Councilmember Kalen Jones. “We’re not necessarily opposed to all leasing, but this seemed like it was such a large bundle.”

Jones said the city does not often request to be a cooperating agency unless there is a unique circumstance or specific cause for concern.

For example, two parcels located in the Sand Flats Recreation Area were nominated for a lease sale this spring. Local advocates got involved, and ultimately the BLM did not offer those parcels as part of the lease sale.

For the upcoming September sale, the sheer acreage in which interest was expressed was a red flag for Jones.

“The scale of the parcels in which interest was expressed was very large,” Jones said in a conversation with the Moab Sun News, “so that was cause for concern.”

Process overview

Parcels identified in the Master Leasing Plan as leasable can be included in an “expression of interest” from a development company that would like the opportunity to purchase those leases. The BLM evaluates expressions of interest and generates a draft environmental assessment on the included parcels, sometimes choosing not to offer some requested parcels. A public comment period follows during which citizens can share concerns. The sale phase is organized as an auction. If only one company bids on the parcels, they can go for as little as $2 per acre.

Once the leases are sold, they are valid for ten years, during which time the leasing company may or may not decide to develop an extraction operation.

If no development occurs, the company pays the BLM a nominal annual rental fee. If the company wants to develop, it must go through further assessments and procedures. Once a well is producing, the company owes the government a royalty fee on profits earned from that well.

Oil prices low

In addition to environmental and recreation concerns, observers question the timing of an expansive sale.

“Oil prices are falling through the floor,” said Newell. “There’s no need at all for new oil and gas leases.”

With the oil market and entire economy in a slump, the BLM has offered companies a reduced royalty rate on wells operating on BLM land. Usually, once a developed well is productive, the operator must pay roughly 12.5% of its profits in royalty fees. Half of this fee is directed to the federal government, and half is paid to the state where the operation is located. Usually, the state redirects that payment to the local jurisdiction in which the well is operating. Recently those operators were able to apply to the BLM for a royalty rate reduction, possibly to as low as 0.5%, according to a BLM website.

“They’ve cut the royalty rates for those leases from 12.5% down to somewhere in the range of 2 to 3%,” said Newell, referring to operators in Utah who have been granted a reduced rate, “which is going to further impact local coffers, meaning less money is going to the local counties and the local cities from the energy production.”

“At the same time, the BLM is moving forward with new leases in areas that are near those that they’ve just granted the royalty relief. How does that make sense? It doesn’t,” he said.

Jones noted that the parcels in the September sale could very well sell for minimum prices considering the current oil market.

“There may not be as much stomach for competitive bidding and expansion,” he said of the auction phase of the sale. “They might get them for rock bottom prices.”

Newell agreed the company might be anticipating a sparse bidding field for the parcels. He also noted that the upcoming national election may have some developers hedging against a potential change in federal leasing policies in case of turnover in the administration.

Stay tuned

The BLM was hesitant to comment before they completed their initial reviews and draft environmental assessments, which were released just before press time.

The public comment period is now open until July 9, 2020.

Newell expressed doubt that local voices would change the BLM’s course of action, even though the City of Moab was acknowledged as a leasing program partner.

“It essentially lets them weigh in, lets their voice be heard, but it isn’t too different from just allowing the public to weigh in in general. It sounds more official than it really is,” he said.

In Newell’s view, public comments are not seriously considered in the BLM’s evaluation of parcels’ suitability for oil and gas development.

“It’s important that the public weigh in; it’s important that the public have a voice in the management of public lands,” Newell said, but lamented, “The BLM has been diminishing the importance of that voice. That’s unfortunate and frustrating, but it’s, unfortunately, the world we find ourselves in.”

However, Newell pointed out that putting pressure on elected officials has shown results in the past. After local outcry, Utah Governor Gary Herbert intervened to recommend removing parcels in the Sand Flats Recreation Area nominated from the June 2020 lease sale.

The BLM had not responded to questions from the Moab Sun News by press time.

The public comment period on the September 2020 statewide BLM oil & gas lease sale is open from June 9 to July 9. To learn more about the sale and comment electronically, visit https://eplanning.blm.gov/eplanning-ui/project/2000028/510. Written comments can be mailed to the following address: Attn: Oil and Gas Leasing Team, Bureau of Land Management Utah, 440 West 200 South, Suite 500, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101.

82,000 acres close to rec areas in Sept. sale

“They’re right next to a bunch of high-value recreation areas that drive the local economy.”

– Jason Keith

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.