Some information may be outdated.

Photographer, artist and Moab native ViviAnn Rose passed away this month. She was known for her unusual artwork, and she and her immediate family are also remembered for their contributions to the community.

Rose’s life was not an easy one. She battled cystic fibrosis (CF), and outlived the predicted lifespan of CF patients by about 30 years. Her older sister died from the inherited disorder that causes severe damage to the lungs, digestive system and other organs when she was just 14 years old; Rose’s twin sister, Vicki Barker, also had cystic fibrosis and passed away in 2012. In spite of her illness, Rose had a productive career and used her talents to engage in the community.

ViviAnn Barker Rose was born on June 11, 1954, and died on Tuesday, Jan. 2, 2018.

Throughout her life, the desert environment clearly shaped Rose’s spirit and artwork.

“ViviAnn spent a lot of time out of doors, and the beauty of the natural world inspired her every day,” said Castle Valley resident Christy Williams Dunton, who once commissioned Rose to do a mother-daughter photo shoot with her oldest child.

Terrie Carlson is Rose’s cousin and spent her childhood summers in Moab with her and Rose’s family. Carlson described the young Barker twins as active and outdoorsy. They would hike out into the rocks behind the house, Carlson remembered, and pretend they were part of the Flintstones family, using boulders for furniture.

As an adult, Rose continued to indulge her love of nature through hiking and spending time outside. The landscape inspired, and was often the subject of, her photographs.

In a 2016 interview with the Cystic Fibrosis Lifestyle Foundation, Rose recalled receiving a camera from her father when she was 11 years old. Using their family laundry room for a darkroom, he taught her how to develop photos. Rose’s father, Dwaine Barker, was a painter and a sculptor, and encouraged his daughter’s artistic interests.

In college, Rose pursued two other majors before settling on fine art while she attended Utah State University in Logan. In the interview with the Cystic Fibrosis Lifestyle Foundation, she described her decision to commit to art.

“CF factored into my decision to become an artist when I was taking a photography course in college,” she explained. “I distinctly remember setting up a ‘still life’ to photograph and made a conscious decision to commit to a career as a fine artist since I was well aware of the shortened lifespan that comes with the disease … Being an artist hasn’t exactly been practical, but I knew that following my heart would be my greatest fulfillment.”

Evocative, edgy artwork

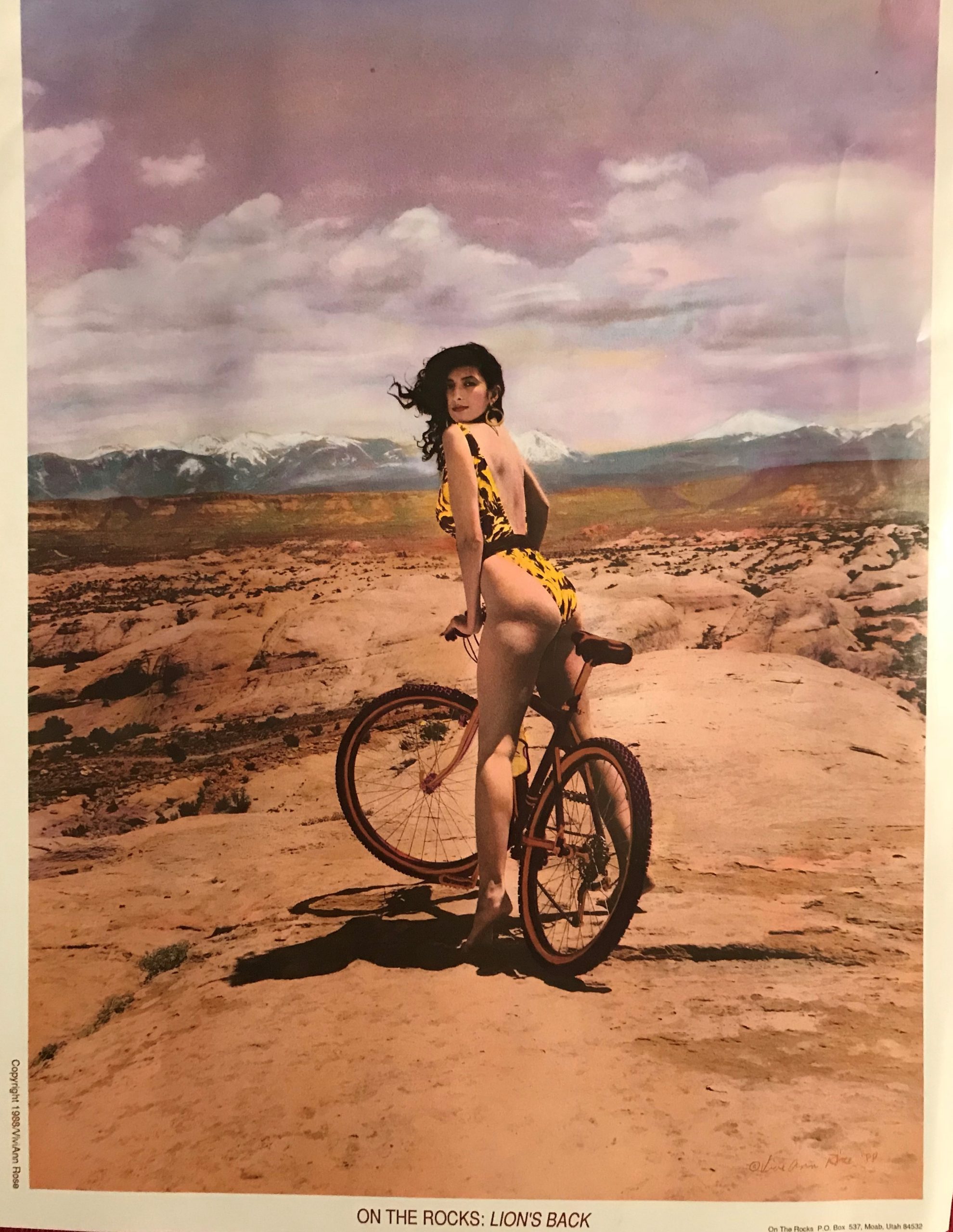

She also experimented with her signature technique while she was in college. Rose’s medium was black-and-white photographs, hand-colored to create a painterly finished work.

She was inspired to try hand-coloring her photos when looking at her parents’ wedding album. All the photos were black and white, except one of her mother and father cutting their wedding cake, which had been hand-tinted. Rose later learned that her mother had been the one to color the photograph.

The effect of the technique produces unique finished pieces. Rose’s work is striking and seems to vibrate with color, even when the tinting is subtle. She displayed her work at shows all over the country, and donated artwork for fundraisers.

Joe Kingsley, who was president of the Moab Chamber of Commerce during the 1980s, remembered Rose’s donation of several works of art to benefit the chamber.

“Her energy and thoughtfulness was instrumental in making it a success,” Kingsley said. “It helped carry us through some hard times.”

Kingsley was touched by another specific work by Rose.

Longtime Moab residents will remember when the now-former Twisted Sistas’ Cafe was called the Poplar Place. The historic building was turned into a bar in the 1960s, and was a hub of Moab social life in the 1970s and 80s. In 1989, the building was badly damaged by a fire. Kingsley, who owned the property at the time, remembered how Rose turned wreckage from the fire into artwork.

She salvaged one of the chairs that survived the fire, Kingsley said, and staged it in a cave to photograph it. She titled the finished hand-tinted print “Waiting for you to come home.”

“The way she pictured it and captured it caught your attention,” Kingsley said. “She really had an eye for photography.”

Rose also donated work to the Cystic Fibrosis Lifestyle Foundation, and to the University of Utah Hospital, where she received treatment.

Rose’s art was often edgy, featuring nude models posed in the wild desert landscape where she lived. Her subject matter sometimes led to memorable encounters.

Once, in earlier times when the pace of Moab was much slower than it is now, Rose gave a workshop for a group of amateur photographers from Japan. She picked a secluded spot in Arches National Park, and directed her group of nude models to pose on a small arch. The workshop was interrupted by a park ranger requesting an explanation of the scene.

After speaking with Rose, the ranger agreed that the workshop could continue, and that he would stand at the entrance to the site to warn any curious tourists that there was “sensitive photography” taking place, and they could proceed according to their own judgment. The result was a cluster of tourists snapping photos along with the workshop attendees, which Rose enjoyed.

Another encounter was not so amicable.

At the 1988 Park City Arts Festival, Rose displayed some of her naturalistic nudes near the front of her booth. Festival officials asked her to move the pieces to the rear of her booth, where they would not be seen by casual passers-by. Rose instead turned the pieces over and wrote on the backs of them, “Censored by the KAC,” referring to the Kimball Arts Center, which administered the festival.

Williams Dunton, the director of development for the Museum of Moab, and an acquaintance of Rose, admired her spunky attitude.

“She was an ecofeminist before ecofeminism existed,” Williams Dunton said. “Her art functioned as her activism, letting it speak for her.”

In 2004, Rose was invited to present her work and to speak at the first Moab Photography Symposium. The director of the symposium, Helen M. Knight Elementary Art Coach Bruce Hucko, remembered the event.

“She gave a heartfelt, image-rich talk rolling in the history of photography and her personal work,” Hucko recalled. “The few who did take her workshop were oh-so-glad they did, because they got her experience, her artistic passion, and gentle spirit firsthand.”

Rose traveled all over the country to display her work and received various prizes and awards, but in her 2016 interview with CFLF, she described her invitation to the Moab Photography Symposium as one of her greatest artistic accomplishments, perhaps evidence of how she treasured her hometown.

The impact Rose left on the town and especially on certain residents won’t be forgotten.

“Her provocative eye for the tender and tough landscape of the body and of this red earth told true and beautiful stories, not always comfortable stories,” Williams Dunton said in appreciation of Rose’s work. “We were lucky to have a last showing of her work in 2015/16 at the (Moab Arts and Recreation Center). We were lucky to have her, period.”

Moab artist ViviAnn Rose dies at 63

She was an ecofeminist before ecofeminism existed … Her art functioned as her activism, letting it speak for her.

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.