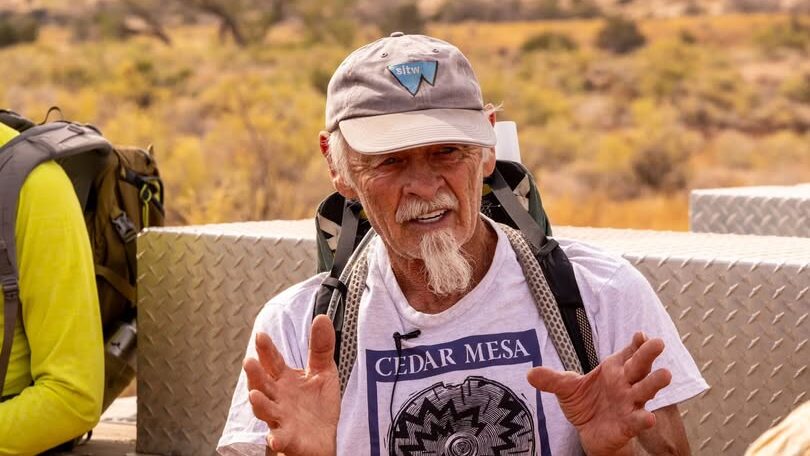

Science Moab recently spoke to paleontologist Randy Irmis. Randy teaches at the University of Utah in the Department of Geology and Geophysics, and is the curator of paleontology at the Natural History Museum of Utah.

Some of Randy’s work involves studying fossils from the Triassic Chinle formation in Southern Utah, and comparing them with similar assemblages that have been found in the Chinle at different latitudes across the Colorado Plateau.

The Triassic period ran roughly from 250 to 201 million years ago, and it followed the Permian Triassic Extinction event, the largest mass extinction in Earth’s history.

Science Moab: Can you describe the environment at the time the Chinle was being deposited?

Irmis: The reason the Chinle has preserved so many fossils is that the sediments were deposited largely by rivers and streams and seasonal floods on floodplains and those are great places for fossils of plants and animals to get preserved because they tend to get buried pretty quickly.

This was a relatively dry river system, not unlike some parts of the Southwest today, where at some times of the year the rivers would’ve been going fast and have a lot of water going through them, but during the dry season, they would’ve been a lot smaller. There would have been lots of vegetation around the rivers and streams, but as you got away from that, it would’ve been perhaps more sparse. So not a desert, but with very marked wet and dry seasons.

Science Moab: What sort of critters would’ve been living in these environments?

Irmis: I’m a vertebrate paleontologist, so that means I largely study animals with backbones. So we’ve got all different types of ray fin fishes in the rivers and streams. We have even freshwater coelacanths, so these lobe fin fishes that are only found in the deep ocean today.

We have large flathead amphibians whose heads and jaws look like toilet seat bowl covers. They could haul themselves out on land occasionally, but they were spending most of their time in the water.

There was a whole host of different types of reptiles as well. The most common reptile that we find fossils of is an animal called a phytosaurus. It’s very poorly named, because phyto means plant, but these were most definitely meat eaters. They had very long snouts with lots of teeth, not unlike a crocodile or alligator. And overall, their body shape looked a lot like a crocodile, an alligator, but they’re not related to modern crocodiles and alligators in any way. So they’re a great example of what we call convergent evolution, converging on the same body shape because of similar ecology and evolutionary pressures. So there are lots of other critters, but that’s just a sample.

Science Moab: You’re looking at the Chinle within the Bears Ears National Monument and more specifically near Indian Creek. What brought you to choose that locale as a place to start looking?

Irmis: There’s tons of Chinle formation in Southern Utah, so you could pick a lot of different places to work. I had been collaborating with Andrew Milner from St. George in some outcrops of the Chinle formation a little bit east of the monument and, and we had really good success finding fossils there.

So it was a natural progression to move westward to the next set of outcrops in the Indian Creek area, which looked very similar. So we thought there was a good chance of finding stuff there, and we did a few brief trips out there to test that out. And it looked like there was lots of fossils and because of all the different canyons there, especially these little side canyons, and there’s a lot of possible exposures of the Chinle formation to look at and define fossils in.

Science Moab: Over the 10 years you’ve been working on this, can you tell us a bit about what you have found in the Chinle in terms of fossil assemblages?

Irmis: We’ve found a lot of different fossils, and they’re not only bones and teeth and skeletons, but also plant fossils, leaf fossils, as well as what we call trace fossils, so things like fossil footprints. We’re building up a picture of the entire series of ecosystems that’s preserved, so there is petrified wood, we have conifer leaves, and we also have leaves of a very strange palm plant called Sanmiguelia. It’s not related to modern palms at all, but the leaf structure looks similar and it seems to be a Triassic plant that was particularly adapted to this very dry environment.

We find lots of shells of freshwater and terrestrial molluscs. One of the highlights, I would say, is some of the fish fossils. So most of the time in the Chinle formation you find lots of fish fossils, but they’re isolated scales and things like that and you can’t really do much with isolated scales in terms of identifying exactly what species you have. But we’ve found some amazing fish fossils where all the scales and bones are still in position. They’re what we call articulated. So we can tell a lot about the different types of fin fishes and freshwater coelacanths living during this time.

There’s also some freshwater sharks that are living in these rivers and streams too. And I mentioned earlier these flathead amphibians, they’re called metoposaurs, and we find some of their bones. We find a lot of phytosaurs, the crocodile-like reptiles that have lots of teeth and lots of pieces of bony armor and long snouts. We’ve got some really spectacular, beautifully preserved skulls that we’re still working on.

So that’s a broad spectrum. The way to sum it up would be when we started working out in the Indian Creek area, there were maybe a handful of fossil sites that had been documented in the Chinle formation. I think we’re probably close to documenting over 300 sites now.

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.