The Returning Rapids Project documents San Juan River recovery with first comprehensive survey since 1921

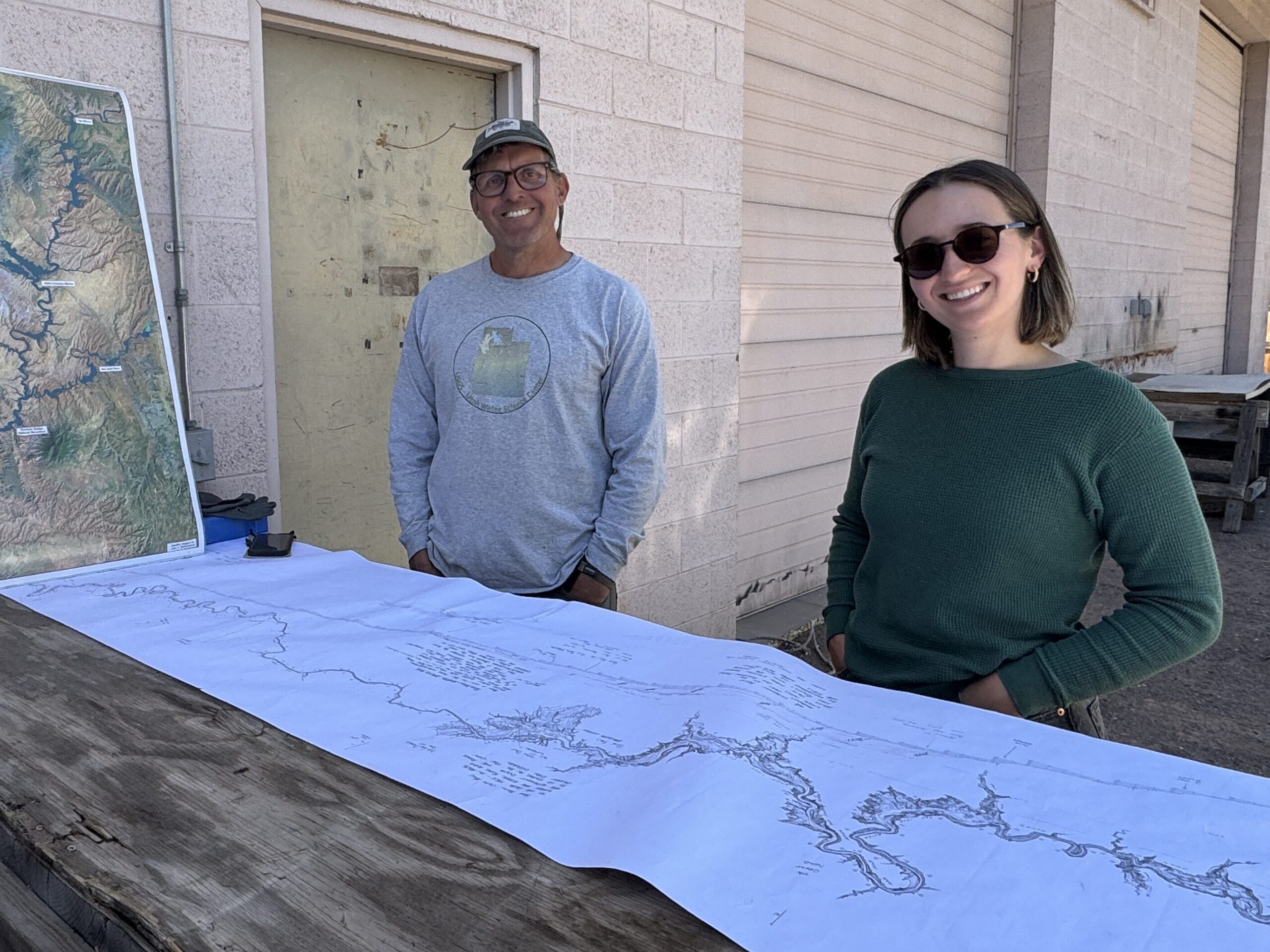

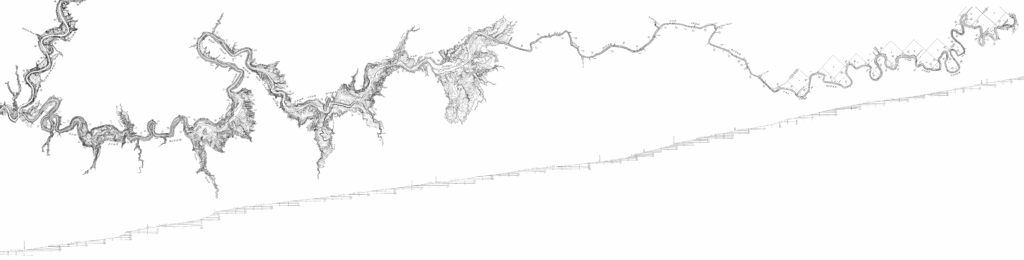

Mike DeHoff stood above a long wooden table and unrolled a black and white paper map of the San Juan River corridor. DeHoff, the principal investigator of the Returning Rapids Project, stood beside Isabel Adler, who joined the team in 2024.

The Returning Rapids Project, founded in 2019, is a Moab-based citizen science initiative that documents how the Colorado River system is recovering as Lake Powell water levels drop due to ongoing drought.

In a recent conversation with the Moab Sun News, DeHoff and Adler referenced the enormous five-foot-long map as they recounted the mid-April survey of 94 miles of the San Juan River.

The survey ran between Mexican Hat and Paiute Falls and closely mirrored the original 1921 United States Geological Survey Geographic Hydrographic reconnaissance, which was conducted to understand how the river could be harnessed for resource development.

The 1921 data, in conjunction with surveys of the Colorado River in Cataract Canyon and Marble Canyon between 1921 and 1923, informed the current management infrastructure seen on the Green, Colorado and San Juan rivers.

“For reasons not entirely known, but suspected by many river runners, it seemed like any large repeat survey of the 1921 efforts were never put into motion. Until this year!” says DeHoff.

Century of Change

DeHoff explains that in the 104 years since the initial survey, the San Juan River has experienced trans-basin diversions, heavy oil and gas development, and inundation by Glen Canyon Dam and Lake Powell Reservoir.

“The more we understand what we’ve done to our rivers, the more we could hopefully make better decisions in the future about how to manage it,” DeHoff says.

The impacts of Glen Canyon Dam on the Colorado and San Juan rivers have become more obvious in recent decades. The construction of the Dam was completed in 1966 as a part of the Colorado River Storage Project. The Storage Project was approved by Congress in 1956, designed to regulate the Colorado River and store water for uses including power generation, irrigation and recreation.

Above Glen Canyon Dam, Lake Powell Reservoir was born. It took seventeen years for Powell Reservoir to reach full inundation, between 1963 and 1980. As of July 7th, 2025, the reservoir is barely 32% full.

Rapids Return as Waters Recede

The recession of the reservoir is attributed to the extended drought in the southwest, as well as an increased water demand resulting from population growth, agricultural expansion and the effects of our changing climate.

The dropping water levels of the reservoir have exposed rapids in Cataract Canyon and the San Juan River, once hidden by the upper reaches of the fill line. It was the revival of the rapids in Cataract Canyon that inspired the Returning Rapids Project in 2019. The project now brings together researchers, scientists, river runners, and journalists to study the changes and share the story of the Colorado and San Juan Rivers as the waterways recover from the impacts of the Glen Canyon Dam.

The recession has also exposed the impacts of accumulating sediment above Glen Canyon Dam. According to DeHoff, the effects of the heavy sediment load in the San Juan River were becoming apparent. The San Juan contributes approximately 15% of the total runoff for the Colorado River, but 30-40% of the sediment. When the sediment load met the stilled waters of Lake Powell Reservoir, the river was forced to deposit additional sediment in the San Juan River corridor.

“The river was dropping its load of sediment just downstream of Clay Hills Crossing. This displaced the river from its pre-dam river bed and caused the first of two large waterfalls in the tail-waters of the river as it flowed towards the basin caused by Glen Canyon Dam. Rapids have gone away, been silted in by the sediment and caused certain stretches of the river corridor to be covered in sand bars which challenge navigation,” DeHoff explains.

Measuring Sediment Impact

Clay Hills Crossing sits 58 miles above the historic confluence of the Colorado River. According Returning Rapid’s 2022 River Scout Trip Report, when Powell Reservoir was at full pool, it’s waters backed up all the way to Grand Gulch, 71 miles above the historic river confluence. The impacts of Powell Reservoir were observed by sediment build-up, or aggradation, 40 feet above the Reservoir’s historic highest reaches.

The San Juan is a major tributary of the Colorado River. The headwaters begin in the San Juan Mountains of Colorado before the river passes through northern New Mexico and southeastern Utah, serving as an important water source for the Navajo Nation. The San Juan ultimately confluences with the Colorado River in what was once Glen Canyon, now Powell Reservoir.

Because of the Glen Canyon Dam, the San Juan is experiencing a build-up of sediment, also known as aggradation. Because of aggradation, the character of the river has changed dramatically and the 2025 survey was able to measure the surface elevation to get concrete figures on current presence of sediment.

The accumulating deposit has impacted the San Juan River forty feet further up river than the furthest reaches of Powell Reservoir when it was at its fullest. Above Clay Hills lies a stretch of river jokingly referred to as “Sandbar Alley”, which is a result of the river trying to find its way through the mass of sediment deposit.

Below Clay Hills is a stretch called the Lowest San Juan. The Lowest San Juan is the section that runs from Clay Hills to what is now Powell Reservoir.

“It’s one of the more remote, least traveled sections of any sizable river in Utah,” said DeHoff. “A lot of people don’t go below Clay Hills because there’s this big sign saying, ‘Danger. Take boats out now. Do not proceed.'”

Signs of Recovery

“Sometimes people will say everything under Lake Powell and what was Glen Canyon is forever destroyed,” says DeHoff. “What we see in our research is that’s not the case.”

“It seems like the sediment that’s been left behind has led to really incredible green corridors of native species like willows. We heard so many birds,” said Isabel Adler, who joined the Returning Rapids team earlier this year. “It was incredible seeing these huge cottonwood stands that were so young, maybe like 15 years old, that were just thriving.”

There has never been an Environmental Impact Statement assessing the impacts of the Glen Canyon Dam on the Colorado River and its tributaries.

The information that Returning Rapids is collecting will help inform how the Colorado River system is managed by showing the impact of the sediment.

“The river can recover if given the chance,” he said.

Growing Interest in Remote Waters

Travel below Clay Hills may sound more attractive as word spreads about the transformation of the waterway. However, boaters should consider the skills required for an expedition in such remote terrain. Communication coupled with river skills and appropriate gear for navigating diverse obstacles were some of the foundational aspects that informed the success of the trip.

“It is a very remote, very hard area to travel through and I hope more people get to see it,” DeHoff said.

The desire to experience the Lowest San Juan is tangible.

On May 19, Returning Rapids offered seven people a place on a trip — they received over 80 applicants.

Beth Henshaw, a writer and kayak guide, was one of those participants.

“For most people, it was the first time they had seen the San Juan stretch and Lake Powell,” said Henshaw. “It was all just very about discovery.”

Next Steps

The data gathered from the survey trip is expected to be reviewed and synthesized within a few months. The group is seeking donations to support their work, as some members of their team continue to volunteer their time and expertise. Information regarding donations can be made on their website: returningrapids.com.

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.