Some information may be outdated.

A Gould Construction bulldozer was moving earth to expand Ziegler Reservoir near Snowmass Village, Colo.

The driver, Jesse Steele, uncovered a large bone on Oct. 14, 2010. His foreman, Kent Olsen, took the bone back to his hotel room and identified it as a mammoth’s tusk by using the internet.

Scientists with the Denver Museum of Nature and Science rushed in to see what else they could find.

By the time Snowmastodon Project was completed, nearly 5,000 fossils were discovered. The finding is considered one of the most significant fossil discoveries made in Colorado.

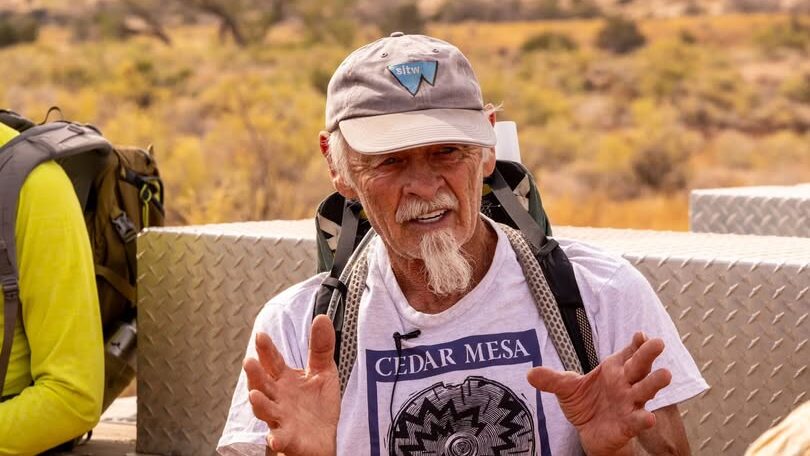

Moab paleo-ecologist Saxon Sharpe will share her experience as part of the Snowmastodon Science Team at 6:30 p.m., Monday, Jan. 14 at the Grand County Public Library.

“It was basically a salvage operation. We had to get stuff out of the ground. They were building a reservoir and we had to get everything out of the area by the beginning of July,” Sharpe said.

The first crew of scientists arrived on Nov. 2 and was able to recover 600 bones in less than 18 days, including the first mastodon skull and remains of a ground sloth to be recovered in Colorado. Work resumed in May and scientists continued to dig for bones until July 1. By the time the dig finished 4,826 fossils from at least 26 different ice age animals were found.

The construction company hired to expand the reservoir would be fined for each day they exceeded in the contract and needed to get back to work.

“This isn’t the optimum way to do a detailed study, but it was the only way we could do it,” Sharpe said. “They were wonderful to work and very much into it. They would use their equipment to help transport casts.”

Sharpe moved to Castle Valley in 1977, shortly after completing her bachelor’s degree in environmental planning. She had the opportunity to work on an archaeology project in Glen Canyon a decade later and began visiting with a professor from Northern Arizona University. He told how “ice age” animals like mammoths, saber tooth cats and camels had lived and died in the area.

“It blew me away,” Sharpe said. “That was the coolest thing I ever heard of and it started me on my path.”

She earned her master’s degree in Quaternary Studies from Northern Arizona University, and then earned a doctorate in geology from University of Nevada, Reno.

For the last several years she has been working as a researcher for the Desert Research Institute.

The Snowmastodon Project site was once the shores of a small glacial lake during the Pleistocene epoch, about 150,000 to 130,000 years ago.

Over 41 different kinds of animals were found, including mammoths, mastodons, ground sloths, camel, deer, horses and giant bison that have horns seven feet wide.

Sharpe’s specialty was not to find the large animals, but the small. She studies freshwater mollusks.

Most of the mollusks she found were the size of a dime. Some were even as small as the period at the end of a sentence.

“It is unusual to have a high elevation site, to have the preservation, to have the number of animals,” Sharpe said. “It was a project of a lifetime.”

They found more than just animals.

“They were digging up plant material that was still green that was 50,000 years old. Everything looked like it was buried yesterday,” she said. “We found sticks that beavers had gnawed on.”

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.