Some information may be outdated.

Updated 2/20/20: In a statement, the Governor’s Office stated that “The Governor appreciates the unique beauty of the Slickrock area and wants to ensure that nothing is done that would be detrimental to the visitor experience or local water quality. He has asked the Bureau of Land Management to defer the lease sales and consider more fully how they might impact those factors.”

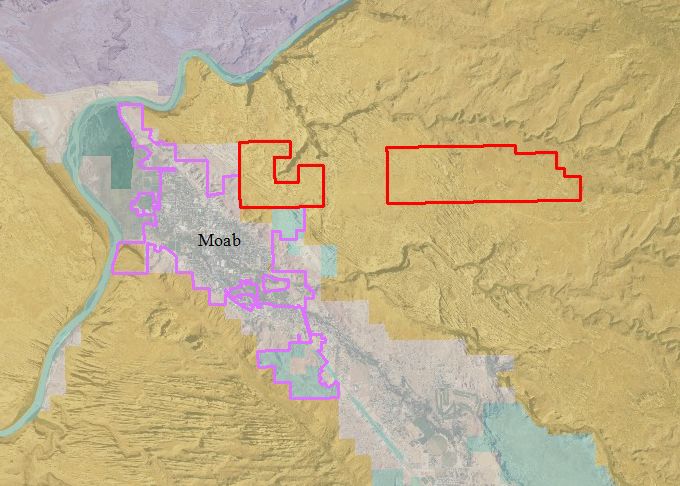

Local community leaders and activists have not forgotten about the two land parcels located in the Sand Flats Recreation Area that have been nominated for the statewide Bureau of Land Management (BLM) June 2020 oil and gas lease sale.

The two parcels, which overlap with the world-famous biking and motorized Slickrock trail as well as a crucial area aquifer, appeared as nominations on the BLM eplanning website a few months ago and have sparked a local backlash that has captured attention from state and national media outlets like the Salt Lake Tribune and Outside Magazine after first being reported in the Moab Sun News.

On Feb. 18, a Moab-based recreation advocacy nonprofit called Public Lands Solutions held a press call about the situation, framing it not just as an isolated example of poor decision-making by the BLM, but as a poster child for the wider issue of energy development being prioritized at the expense of other uses and values.

Public Lands Solutions Managing Director Ashley Korenblat was joined on the call by Moab business owner and City Councilmember Karen Guzman-Newton, Moab Mayor Emily Niehaus, and Grand County Council Chair Mary McGann.

The two parcels are considered by many to be inappropriate for oil and gas development for a number of reasons. They sit directly on top of an extremely popular recreation area, not to mention on top of the Glen Canyon aquifer, the sole source of drinking water for most of the 10,000 or so residents of Grand County.

The parcels are in close proximity to the town of Moab, home to over 5,000 residents, and within a couple miles of Arches National Park, which draws around 2 million visitors each year and is treasured for its scenic beauty. The parcels are also closed to surface development, meaning any drilling would have to be conducted horizontally underground from a nearby parcel outside the recreation area. “Directional” or “horizontal” drilling of this kind is a technically difficult and expensive procedure, and it is unlikely, Korenblat said, that the surface development needed for the operation could be located more than one mile away from the parcels.

Those who oppose allowing leases on the parcels fear potential negative effects on the air quality, water quality, landscape, dark night skies, wildlife and natural vegetation, and visitor experience on the parcels and surrounding areas if the leases go forward and are opened to development.

Both the Moab City and Grand County councils have passed formal resolutions opposing the inclusion of the two parcels, numbered 11 and 12, in oil and gas lease sales, and many Grand County citizens have spoken up in local editorials and on social media with the sentiment that these particular places are not the right sites for energy development.

“You wouldn’t show up to church in your ‘Burning Man outfit,” said Guzman-Newton, who co-owns a local bike shop, during the press call, illustrating how inappropriate she considered oil and gas development in Sand Flats.

Niehaus opened her remarks during the call with what she called a “field report” from Sand Flats.

“It’s a bright sunny day and recreationists are enjoying their morning up at Sand Flats, biking, hiking, jeeping, riding ATVS, and for those who have not yet left their campsites, they’re sipping their hot coffee and watching the morning sun cascade its light over the gorgeous slickrock domes that we love so much,” she said. “And nestled safely under all this fun and beauty, is Moab’s single source aquifer, the only water supply for the City of Moab… the water we drink after a fun day on the trail.”

Her imagery summed up many of the reasons locals value the parcels in question.

All spokespeople on the call emphasized how outdoor tourism is a major element of the Moab economy, and a more valuable one than extractive industries.

Guzman-Newton recapped how after the collapse of the uranium industry which supported Moab until the 1980s, the popularization of mountain biking provided the momentum to turn the city into a thriving recreation hub. That outdoor recreation turnaround actually began on the world-renowned Slickrock bike trail, the area being explored for leasing.

McGann said the Sand Flats Recreation Area, which sustains itself on its own entry fees, garners $700,000 annually in direct revenue, and produces a net value of $7 million to the local economy.

“Communities are benefiting from the recreation economy and there’s just no reason to undermine that at this point,” said Korenblat in a separate interview with the Sun News. “It just doesn’t make economic or business sense to lease every nook and cranny when there’s certain places which local communities have determined have higher and better uses.”

Korenblat is the CEO of the Moab-based bicycle touring company Western Spirit Cycling in addition to her role at Public Lands Solutions. She said the nonprofit “helps communities that are pivoting from dependence on resource extraction to recreation.”

“Most of what we do is really positive, but every now and then we have to go on the defense,” she said of the organization, citing the Sand Flats parcels’ nomination for lease as one of those times.

Niehaus and Korenblat also pointed out that there are other parcels in less sensitive areas of Grand County that are under lease and have not yet been developed for extraction.

Korenblat believes the whole mineral leasing system needs to be revisited. Right now, oil and gas lease sales are guided by the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920, a time when, Korenblat says, the priority was to spread out the financial risk of mineral exploration.

Local economies based on tourism and outdoor recreation weren’t a part of the calculations back then, she noted.

“We’re using a 100-year-old law to determine how we do this stuff right now,” she said. “By definition, it’s anachronistic. Things have changed. We have lots of different needs in 2020 than we did in 1920.”

She said the fact that a parcel as special as those on Sand Flats could be nominated “willy-nilly” for oil and gas development demonstrated the need for a change, pointing to Nevada Senator Catherine Cortez Masto’s introduction of the “End Speculative Oil and Gas Leasing Act of 2020” to the U.S. Congress. The legislation aims to concentrate oil and gas development in areas with higher development potential and limit it in vulnerable areas.

Korenblat also lamented the release of a 2017 executive order issued by the Trump Administration, which has become known as the “energy dominance” policy. The order directed federal agencies to “review existing regulations that potentially burden the development or use of domestically produced energy resources” and revise, rescind, or suspend any rules that “unduly burden” domestic energy development beyond what is needed to protect the public interest and comply with the law.

Korenblat said the effects of the policy were evident in her work with land management agencies through Public Lands Solutions.

“There are systems of communication and relationships between cities and towns and local BLM, and local BLM and the state, and there are all these methods of communicating that have all just been thrown out the window.”

Guzman-Newton agreed.

“In the past, local BLM officials were expected to weigh in [on oil and gas leasing decisions],” said Guzman-Newton. “This discretion has been completely abandoned since the current administration’s ‘energy dominance’ agenda.”

“It’s our understanding at this point that [local BLM officials] did request that [the parcels] be deferred and the state replied that they were not able to pull them,” said Korenblat.

BLM officials did not specifically confirm that statement.

“The Utah State Office works closely with the field and district offices when considering parcels for quarterly oil and gas leases,” said Rachel Wootten, public affairs specialist for the Utah BLM state office, in an email to the Moab Sun News. “BLM Utah does not discuss deliberative decision-making.”

Guzman-Newton said the Utah State BLM office “appears to be completely oblivious to the economy of our region.”

Niehaus said her hope was that Utah Governor Gary Herbert would recommend to the director of the state BLM that the parcels be removed from the sale. Herbert took a similar action in 2017 in Washington County, when three parcels located near Zion National Park were scheduled to be included in a lease sale in June of that year. Herbert wrote a letter to then-State Director of the BLM Ed Roberson, saying those three particular parcels were not good candidates for oil and gas development. In that case, the BLM complied with the Governor’s request.

Niehaus said she has spoken with staff members serving Utah Senator Mike Lee as well as with Utah Representative John Curtis, and that both representatives are aware of the issue.

“As we all know, it’s been busy in Washington, D.C. with other issues; I’m hopeful that our governor is going to take action,” Niehaus said. “I believe that the representatives that we have understand the need to balance between oil and gas and recreation… We have an awesome governor in Utah that understands balance.”

The public comment period on the lease will be open from Feb. 20 to March 3. Comments can be submitted on the eplanning website for the sale at https://bit.ly/3bRebBu.

The public comment period on the oil and gas leases will be open from Feb. 20 to March 3. Comments can be submitted on the eplanning website for the sale at https://bit.ly/3bRebBu.

City says no oil and gas in Sand Flats: Council approves letter opposing BLM move – Jan 30, 2020

Sand Flats areas considered for oil and gas lease – Jan 16, 2020

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.