Some information may be outdated.

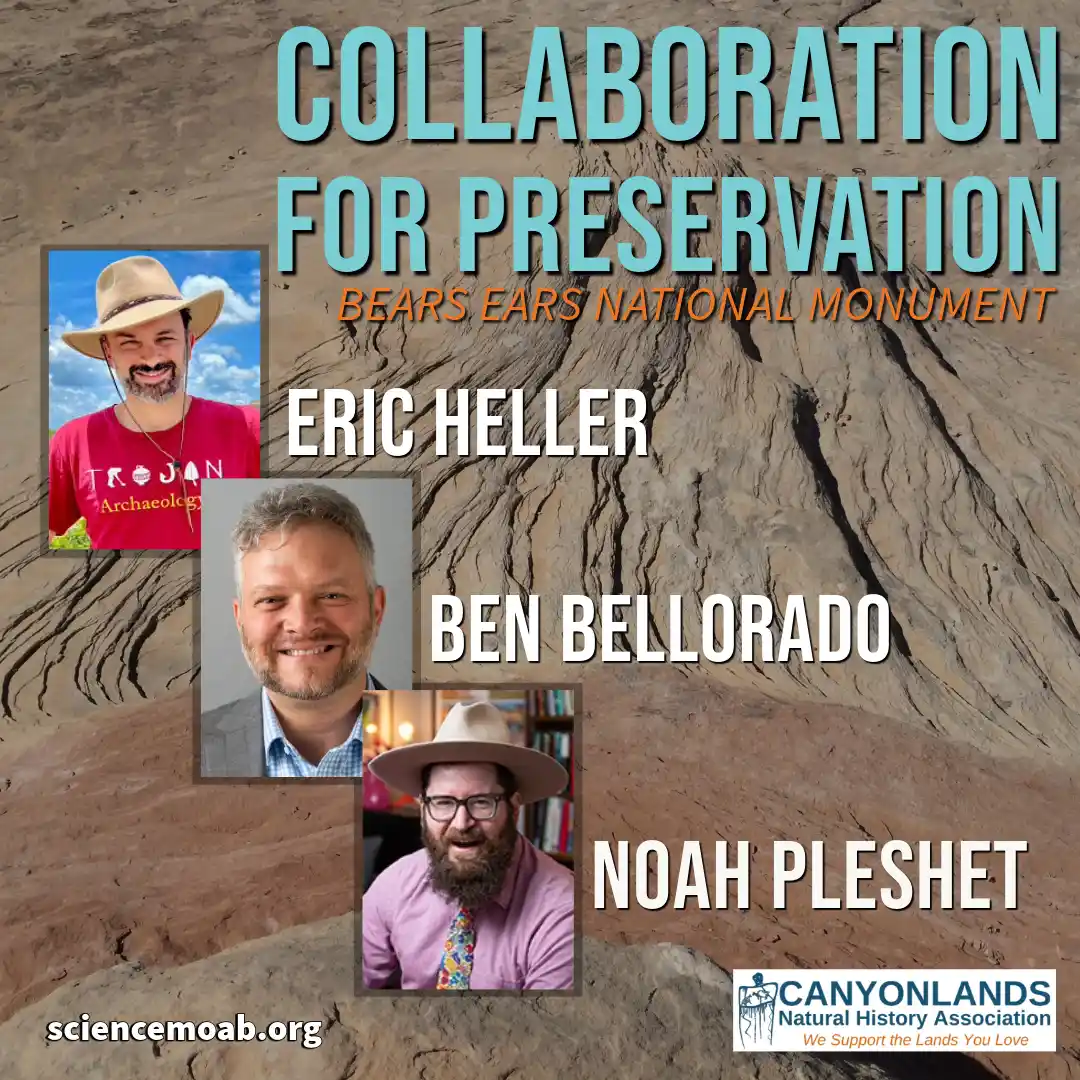

Eric Heller, Ben Bellorado, Noah Pleshet

Science Moab spoke with Eric Heller (University of Southern California), Ben Bellarado (University of New Brunswick), and Noah Pleshet (Arizona State Museum) about the intersection of science, art, and ethnographic interviews that come together to create a virtual reality platform in which to experience sacred sites in Southeast Utah.

Science Moab: Can you describe the Bears Ears Digital Cultural Heritage Initiative (BEDCHI) that you are all a part of?

Heller: It’s a really complex thing to describe, honestly, because there are multiple parts all moving at the same time that are mutually reinforcing one another. We are kind of in the content creation business where we’re producing a virtual reality (VR) experience and photogrammetric models for scientific purposes, but at the same time, we’re also working with Native Tribes in the region to not only produce that content, but also to teach and train and work together to create these models and ultimately these VR experiences that are deeply informed by their vision and their design criteria.

Pleshet: The Bears Ears Digital Cultural Heritage Initiative came out of long-term work that’s been done at a variety of sites in Bears Ears National Monument by Dr. Bellarado and Dr. Heller. The goal is to collaboratively produce virtual reality experiences with descendant communities who have ties to the area and to also involve youth and others from the communities in both interpreting these places for these experiences and in producing content.

Science Moab: Who is collaborating to make this happen?

Bellorado: In addition to our three institutions, that’s University of Southern California, University of Arizona’s Arizona State Museum and the University of New Brunswick, we’re working with the National Forest Service, specifically the Monticello Field Office of the National Forest Service, which is in charge of the Manti LaSal National Forest. We are also working with the Bureau of Land Management, the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County in California, and The Edge of the Cedars State Park Museum in Blanding, Utah. The Tribal groups we’ve been working with on this particular part of the project are the Navajo Nation Historic Preservation Department and the Zuni Cultural Resource Advisory Team.

Science Moab: You are trying to create a virtual reality product for Bears Ears. How do you physically go about digitizing a site and or preparing it for virtual reality?

Heller: We largely use a technique called photogrammetry, which is essentially the art and science of taking a series of overlapping pictures, then using software that will allow you to stitch those pictures together and find common matching points in 3D space using the principles of parallax. At one of our sites at Horse Rock, we have some 2,600 photos taken with a drone and a handheld DSLR camera. We build up a model that’s suitable for virtual reality by using a variety of software packages including Agisoft Metashape Pro, Blender, and then, ultimately, the Unreal Engine (a game development platform) to do the visualization.

The end result that we’re going for is taking these photogrammetric models into the game development platform and then splicing in other types of media, primarily audio content derived from ethnographic interviews typically conducted directly on site. Then, when the user puts on the VR headset, will be able to wander through a virtual environment and as they encounter different content areas through location-based triggers—or when they look at a particular thing, those audio tracks will cue—and they’ll be able to listen to the largely interpretive content directly from our our Native partners.

Science Moab: Do you see this type of initiative going far into the future?

Heller: I certainly do. This particular round of funding really allowed us to actually do some of our early forays into scanning and producing visual content, but also to work with descendant communities, both as content creation partners and in a mutual teaching and learning relationship as well. There’s a lot of potential for this kind of work. We’re certainly not the only people working in this space, but I think one of the things that really sets us apart is we’re deeply invested in building long-term relationships with descendant communities.

The technologies are relatively accessible…you can learn the tech in a day, but to master it and to really get to a level where you feel the confidence to begin crafting your own narratives and sharing your own visual stories, that takes years, and we’re here for that.

Bellorado: The thing we really focused on this year was switching from just creating the model to actually teaching photogrammetry and ethnographic interviews as well. That’s the workshop model we developed, and it captured people’s interest in different ways. We had Tribal students and college students attend our workshops and we showed them how photogrammetry and ethnographic interviews work.

Pleshet: It has really been a long period through which we’ve developed these relationships, with descendant communities, federal agencies, and the universities and museums we’ve worked with. What really got things to a different level this summer is the focus on an educational aspect, both in field context and in these workshops where we looked at the photogrammetric data.

What really got people excited and thinking differently is that we shifted the focus to the education and knowledge aspect and away from the model product aspect. Going forward, the perspectives of both the descendant communities and the agencies are really interested in this kind of education and knowledge focus of the BEDCHI project.

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.