Some information may be outdated.

Local paramedic hosts jiu-jitsu practice sessions

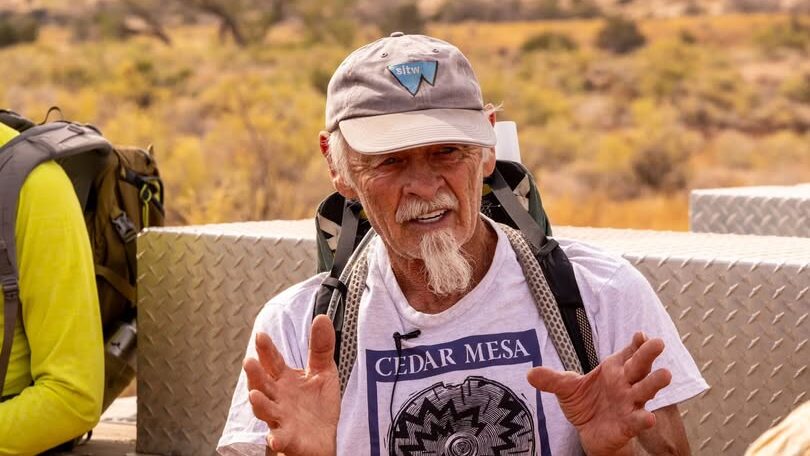

“I really, with all my heart, believe that the physical and mental benefits are massive,” said Pat Noonan, a paramedic with Grand County Emergency Medical Services, about the martial art of jiu-jitsu.

Noonan holds a blue belt in the sport, and has been organizing informal training sessions at the EMS building. The meetings are free, no experience is needed, and anyone is welcome. The days and times of the meetings change; Noonan sends out a group message when he plans to hold a session.

“I’m happy to train with anybody who wants to,” Noonan said, adding that he’s not especially advanced in the art—a blue belt is only one level above the beginner’s white belt. Beyond that are purple and brown belts, with a black belt indicating the highest level of mastery (though there are levels within the black belt category as well). Noonan said it takes a long time to advance levels in jiu-jitsu, and an average of 10 years of regular training to achieve black belt.

“It could easily take me 20 years,” he said. But he is glad to share what he knows and grapple with both experienced jiu-jitsu practitioners and newcomers.

Jiu-jitsu is a grappling sport—there are no kicks or punches. The goal is to get the opponent to the ground and compel them to submit, using a joint lock, compression lock, or chokehold. The fighting style originated in Japan; in the 1910s, a Brazilian family with the surname Gracie discovered the sport through a demonstration given by a traveling Japanese fighter. The Gracies pursued mastery of jiu-jitsu and began teaching others. The discipline that is widely popular today is known as Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu.

“They’re the family responsible for making it so popular,” Noonan said.

Gracie family members helped to create the first Ultimate Fighting Championship in 1993, in which fighters of all weight classes and using different styles were pitched against each other. Jiu-jitsu proved very effective against other styles of martial arts, and most martial artists now are familiar with the form.

“They all have to have somewhat of a jiu-jitsu game,” Noonan said.

Noonan got interested in jiu-jitsu in 2016 while working as a cook in a restaurant in New York. His employer loved the sport, and Noonan was curious about it.

“He showed me some stuff at the restaurant,” Noonan said, and later he went to the jiu-jitsu school his employer attended. He was hooked.

It was around that same time that Noonan started working seasonally in Moab. He first came to town for long-distance running events and to enjoy the landscape, and he now moves back and forth between Moab in the summers and New York City in the winters, working as a paramedic in both places.

When Noonan started working in Moab, he looked around for a place to keep training, and found out that a couple of guys—both named Kevin—hosted an informal jiu-jitsu club at the South Town Gym. Noonan joined in.

Eventually both Kevins left town, and Noonan took over organizing the group—scheduling meeting times and offering instruction for beginners.

Later he moved the practice sessions from the gym to the new Grand County Emergency Medical Services building. The move made sense, he said, as many of the participants are EMTs or law enforcement officers.

“Any first responder needs to be able to defend themselves,” Noonan said. “They definitely end up in violent situations more than the average person.”

That might mean encountering an “agitated or combative” psychiatric patient, who needs help but is uncooperative with EMTs. Jiu-jitsu also has self-defense applications.

Aside from its practical uses, jiu-jitsu is good for the ego, according to Noonan: “It’s extremely humbling—to be submitted by a 130-pound girl is pretty humbling.”

He said this happens to him often at his training school in Brooklyn.

While jiu-jitsu can help keep one’s ego in check, Noonan said it can also build a healthy sense of confidence. Awareness of skill and ability can help a person remain calm in moments of stress, and presenting an assured demeanor can diffuse an intense or confrontational situation.

“A lot of what I’m trying to do, as an EMT and as a person, is be calm and make good decisions,” Noonan said. “In order to make good decisions, I need to be calm.”

Jiu-jitsu requires analyzing and strategizing in the midst of immediate stress. Noonan believes this can be helpful for anyone, not just people who respond to emergencies for work.

Noonan preps for jiu-jitsu sessions by spreading out padded workout mats on the floor of the ambulance bay at the station. He starts out with a light warm up—some jogging, rolls and repetition of some fundamental jiu-jitsu movements. Then he explains and demonstrates different positions and techniques, and lines out a sequence for the group to practice in pairs. The session ends with live grappling. In five-minute rounds, participants pair up and try to get their partner to “tap out.” Experienced grapplers meet beginners at their level, allowing them to practice and learn.

There’s no requirement for participants to have any previous knowledge or experience. Noonan said he comes up with a couple of “lesson plans” ahead of time, and chooses one based on who shows up, aiming to teach to the lowest experience level.

All participants must sign a waiver; those under 18 must have a parent sign. Noonan is willing to teach older teens, but said he’s not prepared to teach classes for kids.

Participants should show up clean, with trimmed finger- and toenails, and ready to be barefoot, in socks, or have wrestling shoes—regular shoes aren’t allowed on the mats. Also recommended are an open mind and a readiness to learn—and maybe be humbled.

To get notified about training sessions, contact Pat Noonan at pnoon1@gmail.com.

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.