Some information may be outdated.

Trails to historic hauling equipment to open this summer

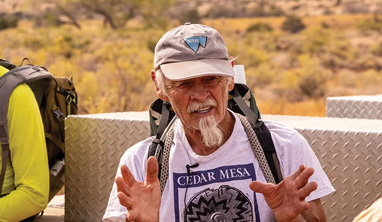

Jim Wells first worked at Dead Horse Point State Park as a ranger in 2016. That season, a proposed project would have placed an interpretive sign near a piece of historic hauling infrastructure above a spectacular viewpoint. The project didn’t end up happening that year, but the vista made an impression on Wells. When he returned to Dead Horse Point this summer as park manager, one of his top priorities was opening that viewpoint to visitors.

“As a ranger, I always wanted to open up that landscape,” Wells said. “No one’s been there since the 50s.”

A new system of hiking and biking trails, totaling between 5 and 6 miles, will open access to that landscape. The trails will be moderate; bike routes will follow old roads. Wells hopes the trails will be ready to open by summer of 2024, and give visitors a chance to explore local history and enjoy the dramatic scenery of the park.

Oil’s heyday

Wells contacted the Moab Museum for information about the historic infrastructure, and received a report summarizing research compiled by Moab archaeologist Jody Patterson.

According to the report, in the early 1950s, Colorado-based company Americol Petroleum struck a profitable oil deposit near the Colorado River, close to the current location of the Intrepid Potash Mine. Speculation and media excitement about oil prospects in Southeast Utah rose in the early 20th century, but it wasn’t until mid-century that Utah’s oil industry took off. According to the Utah Division of State History, Utah went from producing half a million barrels of crude oil a year in 1949 to producing 40.1 million barrels in 1959. (For comparison, a chart from the Utah Department of Natural Resources indicates that the state produced about 45.4 million barrels of crude oil in 2022 and 35.8 million in 2021.)

Americol Petroleum’s well, called Mason No. 1, was one of the first in the area that was commercially viable. However, at the time, there were no roads to the well site; Potash Road hadn’t yet been built. Supplies and equipment were brought to the well site by boat on the Colorado River, but that was a risky endeavor: two such boats sank in 1951.

The company needed a way to get its product to buyers. While the well was still being developed, Americol Petroleum was busy establishing roads to connect the extraction site to transportation routes; the company also made plans to pump the oil up from the canyon bottom to storage tanks on Big Flat Mesa, to a site that is now within Dead Horse Point State Park. Four 2,500-barrel capacity tanks once stood at a spot now called Miner’s Point, which was recently reopened to Dead Horse Point visitors and can be reached on foot or by bike via an old road. No trace of the tanks exists now aside from the dirt road that led to them.

Trucks could reach the tanks on Big Flat Mesa by road, load the oil and transport it to refineries. To get the crude oil from the well site to the storage tanks, Americol Petroleum built a flow line: 16,000 feet of 3 ½ inch metal pipe that would pump the oil from the well site to the storage tanks, 3 miles away and 1,760 feet higher in elevation. Metal tripods, pulleys and 900 feet of braided-metal cable were used to help haul materials up the cliff to construct the flow line.

The flow line was completed by the spring of 1951; that same year, the Potash Road was completed on the canyon bottom. The flow line was shortly obsolete. The Mason No. 1 well was out of service by 1953; the 3 ½ inch pipe was removed, but the tripods and remnants of the cable remained rusting in place along the mesa top through the years.

Dead Horse Point State Park was designated in 1959, just two years after the Utah Division of State Parks and Recreation was established. (The Utah legislature created the Utah Division of Outdoor Recreation as its own entity in 2022, separating it from Utah State Parks, which is now its own division.) The site of the flow line infrastructure has been determined as eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, according to Patterson’s report.

The site

On a sunny November day, patches of snow from the previous night sparkled between shrubs clustered along the rough, sandy road toward Miner’s Point. Throughout a moderate walk following red survey flags, a thick, braided-metal cable poked in and out of the sand. The hike led to the edge of the mesa, where a rusted metal tripod perched hundreds of feet above the river canyon and the Intrepid Potash evaporation ponds, a heavy-duty pulley hanging from its peak.

The La Sal, Abajo, and Henry mountains were all visible in the far distance, each at their own point of the compass. The view is like others at Dead Horse Point State Park in that it is sweeping and impressive; at the same time, it’s a unique perspective not available from any other point in the park. Aside from the historical artifacts, the view is another reason Wells wanted visitors to be able to reach what park officials are calling Potash Point. Park officials will design and install an interpretive sign there, explaining the history of the infrastructure.

Trail system

Dead Horse Point’s existing Intrepid Trail System, which includes over 16 miles of singletrack mountain biking trails ranging in difficulty from beginner to expert, was built in 2014 by the volunteer Trail Mix Committee (which continues to maintain it) with financial support from the Intrepid Potash mine. There are also over 7 miles of hiking-only trails in the park. Biking has become a popular activity at Dead Horse Point; in recent years, local bike rental company Bighorn Mountain Biking opened a location at the park’s mountain biking trailhead.

The trail miles to be added this year aren’t designed with technical riding in mind; instead, they’re meant to provide access to a beautiful area of the park for both cyclists and hikers while minimizing disturbance.

“The bike trails I want to open are just old roads,” Wells said. “My goal is to have as little impact as possible.”

The proposed trails have been surveyed and must be approved by the State Historic Preservation Office and go through a public comment period. If approved, the new trails will be built by volunteers—they shouldn’t need too much technical expertise, Wells said, because the trails either follow existing roads or traverse moderate grades with little vegetation. Wells said volunteer groups such as boy scout troops often contact the park looking for potential service projects; He estimates they’ll need about 20 people to work full-time for three weeks to get it done. Park staff will also contribute to building the trails.

While tourism has become the dominant economic driver in the Moab area, it still exists alongside other industries like ranching and mining. Potash Point is one place where visitors can ponder how these activities overlap in place and time.

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.