Some information may be outdated.

How La Sal pika population trends compare nationwide

The pika is an outrageously cute alpine mammal. Picture a russet-potato-sized mouse, but with no tail, then cross it with a guinea-pig, then give it a rabbit face, but with chubbier cheeks and no long ears. Their distinct call—a quick little, eep!—is almost cartoonish, and can also, research showed in 1985, be individually recognized by other pikas.

But their habitats in talus slopes across the Rocky Mountains make them particularly vulnerable to climate change: being alpine mammals, researchers are looking into whether or not they can tolerate rising temperatures. In 2016, research from the U.S. Geological Survey found that pika populations across the Great Basin, northeastern California, and Zion National Park near St. George, have declined to below historic numbers, apparently due to temperature increases. Johanna Varner, a professor at Colorado Mesa University who studies pikas, said earlier this year the animals have become “a poster child for climate change in a lot of ways.”

So what’s happening with the pika population in the La Sal mountains?

Scott Gibson, a wildlife conservation biologist with the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, said the agency has been conducting statewide pika surveys since 2008. In 2007, the Center for Biological Diversity petitioned the Department of the Interior to list pikas under the Endangered Species Act. The petition recommended that the entire American Pika species be listed as threatened, and that the five subspecies in the Great Basin be listed as endangered due to “their small population size, declining population trend, declining range extent, and the substantial long-term threat that global warming poses to their persistence.”

But in 2010, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service rejected the bid, saying pikas can tolerate warmer temperatures in the summer by hiding beneath rock crevices. At the time, Larry Crist, a Utah field supervisor for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, told the Los Angeles Times that the agency saw “no danger of extinction through 2050,” and said there were no reliable estimates of the pika’s total population across the nation.

Despite the rejected bid, the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources saw the listing movement as a reason to begin surveys. Having reliable data on pika population can help drive land management practices, and add context to the debate.

“Oftentimes, when a species is petitioned, that’s a really strong driver for us to go out and get as much information as we can,” Gibson said. “We really wanted to get a good feel for population trends on pika within the state—as a species, they’re fairly visible because they squeak and run around above treeline … We wanted to get good baseline data in 2008 to inform our monitoring going forward.”

Surveys occurred every three years, in 2008, 2011, 2014, and 2017, and then every six: the latest survey began last month. So far, Gibson said, the pika population in the La Sals has stayed strong; statewide, both pika populations and range increased from 2008 survey data to 2017 data. According to a 2017 survey summary, pika habitats statewide were found in lower elevations than biologists expected; pikas had also recolonized previously abandoned and distant habitats.

Data from this year’s survey won’t be tallied for another few months as researchers finish up their observations through the fall. Pikas live for seven years, so in theory, the animals observed this year would be the offspring of pikas observed in the last survey.

“It’s a species that’s very charismatic, that everyone really likes,” Gibson said. “I think there’s a lot of attention on pikas—we want to make sure we have the data to back up whatever decisions are being made.”

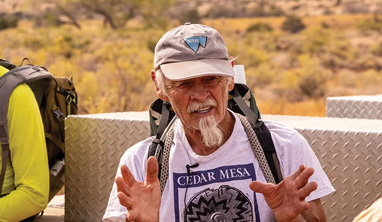

On a chilly day in September, I accompanied Lisa Horzepa and David Steward, seasonal DWR technicians, to a pika survey location between Medicine Lake and South Mountain. Surveying all the La Sal locations took Horzepa and Steward about 10 days worth of work, they said. Survey locations were spread randomly on any talus slopes within the La Sals.

When we arrived at the exact survey location by using a GPS device (after a bit of bushwhacking), Horzepa went first: she had half an hour to try to spot or hear a pika within 100 meters of the spot. The La Sal pikas have their own dialect, Horzepa said—they make a two note call.

“I think it makes them sound cuter,” she said.

When her survey was over, Steward waited another half hour, then went out for his turn. The surveys look for a “minimum number of individuals,” Horzepa said; essentially, they track whether or not pikas live in the area, not how many total there are. Surveyors also take data on tree and shrub cover, to track if vegetation is encroaching on talus slopes.

The surveys aren’t perfect. No pikas were found at this location, but just a few yards outside of the boundary, a pika had made its home on a small talus patch surrounded by a meadow. Pikas like areas like that, Horzepa said—areas where they can find food and have the safety and cool temperatures provided by talus.

If the 2023 data does show a decline in pika population, there are a few experimental treatments the DWR could do, Gibson said. Maybe removing trees and shrubs would help, or limiting human activity, like timber harvesting, in known pika habitats. Ultimately, Gibson said, the data collected during those surveys will guide land management practices.

“We now have a dataset that dates back 15 years,” Gibson said. “It’s a great project.”

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.