Some information may be outdated.

Public comment will be open until Aug. 26

Late last month, the Bureau of Land Management opened a 30-day public comment period for a lithium exploration project that had been postponed in April, pending further environmental analysis.

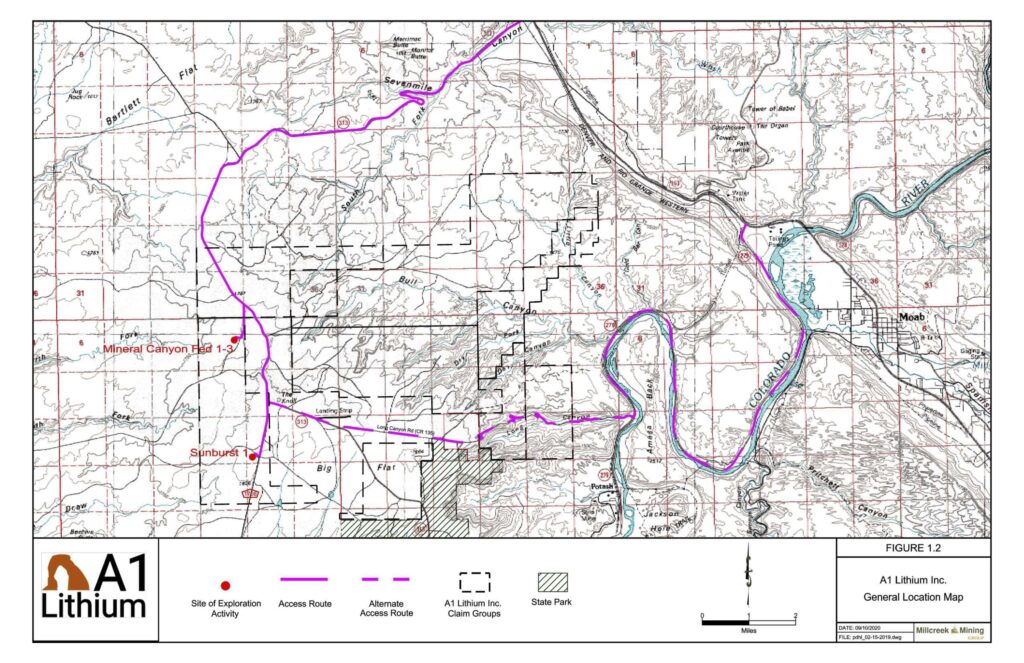

The 30-day comment period opened on July 26 (and will end on August 26). The project, led by A1 Lithium Incorporated (a subsidiary of the Australian company Anson Resources), proposes to reenter two abandoned well bores, Sunburst #1 and Mineral Canyon #1-3, to test brine solutions for lithium. The wells are located eight miles west of Moab off Highway 313—the Sunburst well will be clearly visible from the entrance road to Canyonlands National Park, and the company plans to use 313 to access the wells, according to its initial plan of operations submitted to the BLM in March 2021.

The project was originally approved in September 2022, when the BLM finished an environmental assessment of A1 Lithium’s “Plan of Exploration.” But in December, the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance appealed the decision, arguing the BLM hadn’t considered “a reasonable range of alternatives,” and “failed to consider, analyze, and disclose the impacts of water quantity in this arid redrock landscape—impacts made worse by a decades-long drought and ongoing climate crisis.”

The project was suspended in April 2023 pending further review. In July, the BLM released an updated environmental assessment that “has included updated review of alternatives considered and cumulative impacts on water quantity from potential future fluid and solid mineral development in the analysis area,” according to a press release. According to the revised plan, the project will use a total of roughly 25,000 gallons of water sourced from “local municipalities that have specifically allocated a certain amount of the waters for industrial sale and use.”

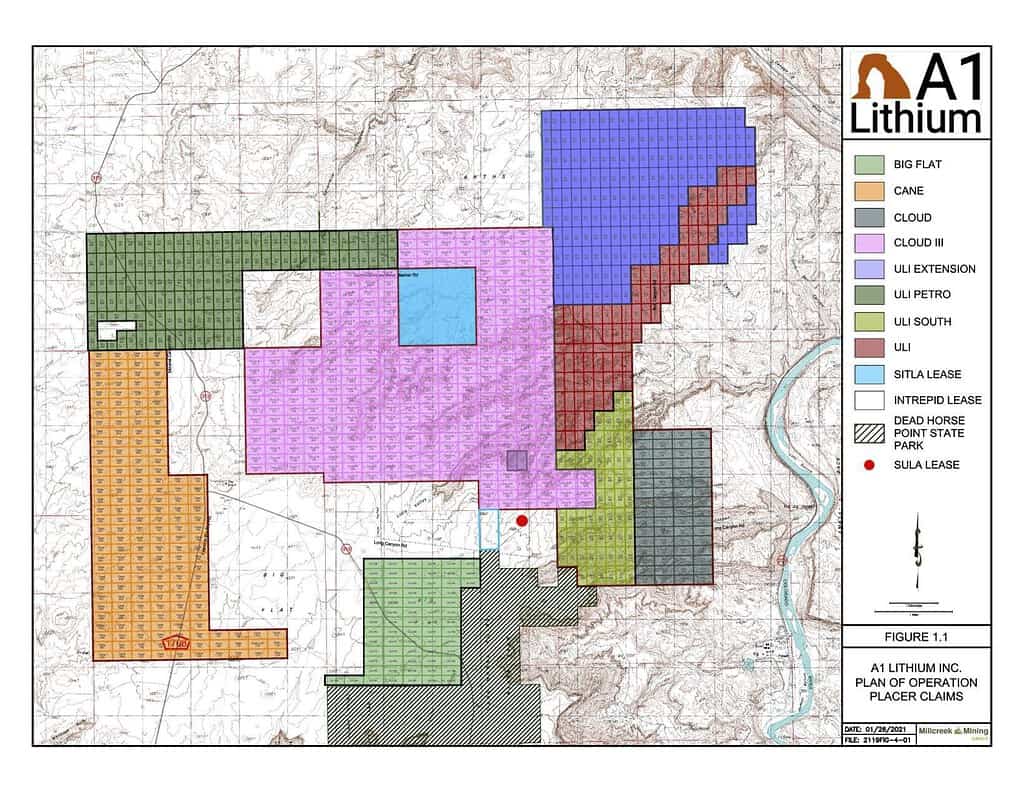

Anson Resources has over 2,000 claims in Southeast Utah, according to Proactive Investors; many of those are in Green River, where in May the company purchased another 0.4 square miles of private land alongside the river with plans to eventually build a lithium mining production facility.

Lithium is a valuable mineral used in batteries, and specifically in electric vehicle batteries, due to its light weight and ability to store energy. According to the Institute for Energy Research (IER), extracting lithium can be “incredibly difficult,” because the mineral is often deposited in other metals and minerals deep below the surface of the earth. The value of lithium has skyrocketed since 2021; most lithium used in batteries is sourced from Australia, Chile, and China.

Dave Pals, the Moab Field Manager for the BLM, said that he’s seen an uptick in requests for lithium exploration. According to IER, the U.S. has over 3% of the world’s lithium reserves, but only one producing lithium mine: the Silver Peak mine in Nevada.

The process to mine on BLM land works like this: companies first submit a request for their exploratory project, submitting a “Plan of Operations” to the BLM. The BLM doesn’t look or ask for those requests, Pals said; it doesn’t have to hit a certain number of approved mining or exploration projects.

The Plan of Operations then goes through a number of assessments, such as an environmental assessment and a visual assessment, which determine if there will be “unnecessary degradation or significant impacts,” Pals said. The public comment period opens, and the BLM addresses “all substantive comments” it receives during that period, according to Public Affairs Specialist Rachel Wootton.

For the A1 Lithium exploration project, for example, a substantive comment would bring up an aspect of the environmental assessment that hadn’t been mentioned—“maybe there’s a recreational use that we don’t know about,” Wootton said.

“Sometimes people want to voice opinions in their comments, which is great, and it’s really good to know those opinions,” she said. “But the substantive comments are new information that we might not know already.”

If approved, the lithium exploration project at the two wells near 313 would take two to four years and directly impact six acres of land. The company thus far has only asked to conduct lithium exploration: if exploration is approved, and then the company finds viable lithium deposits, it would have to present a new plan of operations for mining to the BLM. The mining project would then go through a similar, but entirely separate, approval process. Environmental reviews for mining are much more in-depth, Wootton said.

The BLM would receive no royalties from the mined resource: mining hard rock minerals on public lands like lithium, uranium, copper, gold, and silver, is governed by the General Mining Law of 1872, Pals said, which declares that all valuable mineral deposits in public lands are “free and open to exploration.”

How to comment

Written comments should be submitted by 11:59 p.m. on August 26 and can be submitted through the BLM’s National NEPA register (https://eplanning.blm.gov/eplanning-ui/project/2014014/510) or emailed to BLM_UT_MB_Comments@blm.gov. Comments should reference “A1 Lithium Mineral Exploration Project.”

“Comments on the cumulative impacts on water quantity from potential future fluid and solid mineral development will be especially helpful,” a press release reads.

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.