Some information may be outdated.

The 94-million-year-old fossil also provides clues to reptile evolution

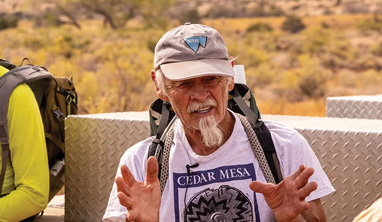

In 2012, Scott Richardson traveled to the site of the Tropic Shale, a geologic formation that stretches across Kane and Garfield counties and through a large swath of the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument.

The shale is made up of mud deposited from an ancient sea (the Western Interior Seaway) active during the latter half Mesozoic era (251.9 to 66 million years ago), which is now called the “Age of Reptiles.” Richardson, a volunteer for numerous paleontology museums and organizations, had been fossil hunting in the Tropic Shale before—but that year, he found something special.

When he called Dr. Barry Albright, a professor at the University of Florida with a Ph.D. in vertebrate paleontology, to inquire about looking for more fossils, it was winter, and he didn’t have a lot going on. Might as well have a look around the Tropic Shale, he thought; at the very least, he’d probably find a shark tooth. Maybe a plesiosaur!

Paleontologists started poking around in the Tropic Shale in the early 2000s—until 2012, they had only found fossils of sea turtles, sharks, fish, and plesiosaurs, swimming reptiles that lived from 208 million years ago until their extinction 66 million years ago. Fossils found in the Tropic Shale are deposited from animals that lived and died in the ancient sea: throughout the early 2000s, Albright and Dr. Alan Titus, a paleontologist for the Bureau of Land Management’s Paria River District, discovered and named a number of new plesiosaur species found in the Tropic Shale, plus fossils from a handful of known species.

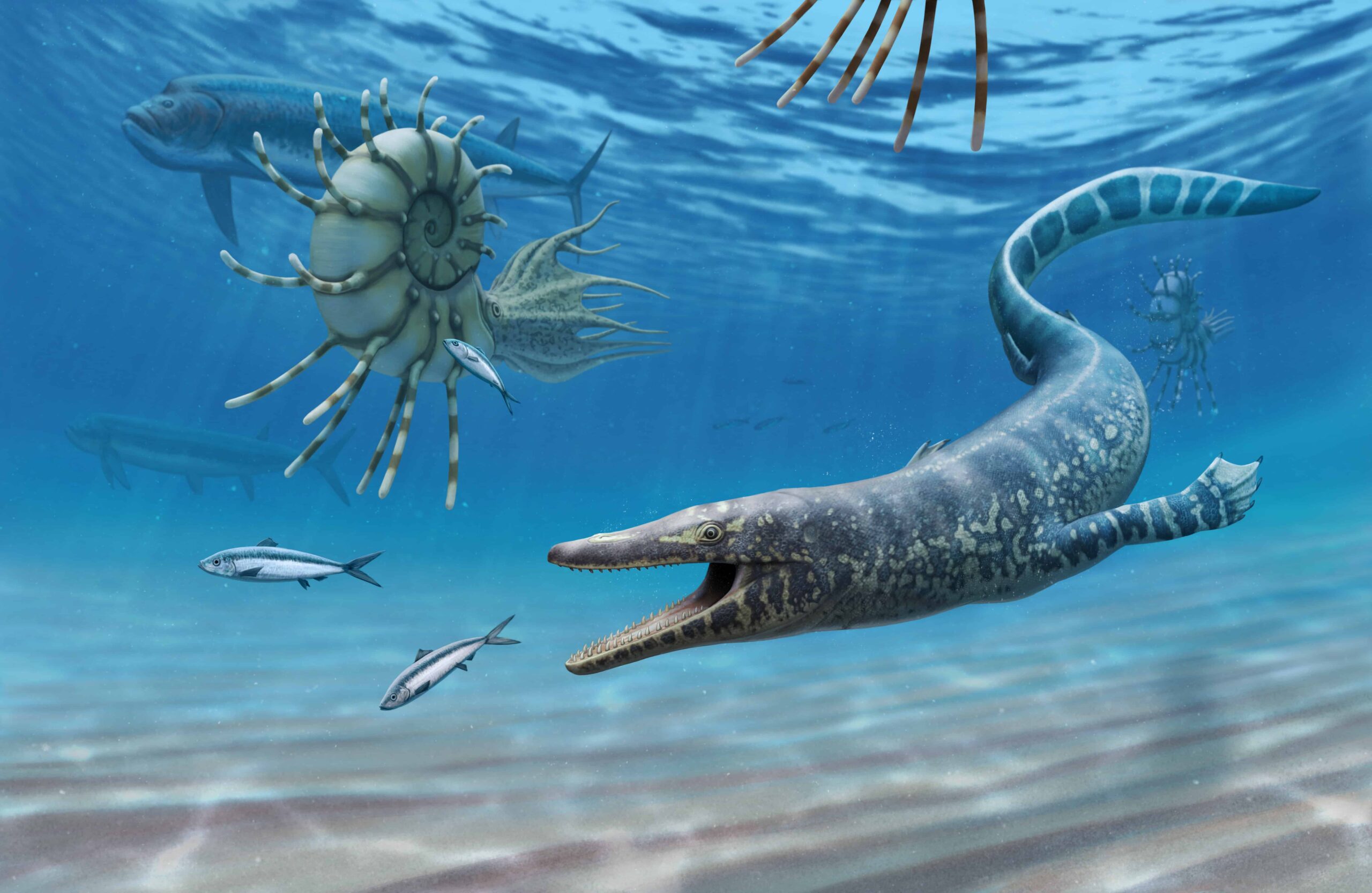

But the plesiosaurs were getting boring. Too many plesiosaurs! Where were the mosasaurs, the land-dwelling reptiles who slunk into the ocean to later rule the waters as massive, 50-foot predators? Mosasaurs first started appearing in the fossil record in the same timescale as the Tropic Shale, meaning any mosasaur fossils found there would be some of the oldest specimens on record, and would help paleontologists piece together the species’ evolution.

“I jokingly told Scott, if he was going to go back into the Tropic Shale, please don’t find any more plesiosaurs,” Albright said. “I said, how about you become a hero, and find us a mosasaur?”

Three weeks later, Albright was delivering a lecture—he’s an Earth Science lecturer at the University of North Florida. His phone chimed: once, twice, three times. He usually ignored it—he’s a good teacher—but this time, he plucked his phone out of his pocket. It was Scott Richardson, sending photos of a fossil—skull fragments and vertebrae—he found in the Tropic Shale.

“I immediately say out loud to my class, ‘holy shit,’ because I realize, these are mosasaur vertebrae,” Albright said. “The dude delivered.”

•••

That was back in 2012. Over the next two field seasons, a BLM and National Park Service team recovered 50% of the mosasaur specimen—the research team members consisted of Albright; Titus; Michael Polcyn, a paleontologist and mosasaur expert at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas; and Nathalie Bardet, a paleontologist at the French National Museum of Natural History in Paris, France. Their research paper discussing the finding was published in Cretaceous Research in June.

The team had to screen thousands of pounds—“maybe tons,” Titus said—of soft sediment to recover tiny bits of bone fragments. They worked with a number of volunteers to do so, including Steve Dahl, one of the longest-serving paleontology park service volunteers.

The specimen had been weathering on the surface for years, according to Polcyn, which is why it took the team so long to identify and sort through the fossil’s anatomy. They ended up with portions of the skull, jaw, and vertebrae; Polcyn also identified that the specimen was three or four years old when it died, meaning for an early mosasaur it was a mature individual.

Their finding is significant in two major ways. First, the fossil is the oldest mosasaur fossil found in North America, at 93.7 million years old: the second oldest mosasaur fossil found in North America is 93.6 million years old (a difference of 0.1 million years, you may scoff, forgetting that’s 100,000 years). 95 million years ago, mosasaur ancestors had just crawled into the ocean from land.

“At this time, they were really peripheral players in the major ecosystem here—they’re just getting started,” Titus said. “[Fossils this old] are rare, because they haven’t come to dominate the environment yet.”

Second, the fossil is from an entirely new species of mosasaur. During lab work, the team discovered this specimen had a novel blood supply to the brain—the primary blood supply was shifted from a branch of the internal carotid arteries to arteries entering the brain below the brain stem.

Paleontologists only know a few things about mosasaur evolution: that they were once land-dwelling lizards, and that by 92 million years ago, a specimen called the Dallasaurus showed that mosasaurs had evolved into an obligate marine form (Polcyn described its form saying, “This thing was not going back on land.”) By 90 million years ago, mosasaurs started to spread across the world. By 75 million years ago, mosasaurs were giants that dominated the ocean food chain.

Paleontologists know this element of the cranial blood supply was seen in future mosasaur evolution, but they didn’t know exactly when it happened. Now they have a better idea.

“Remarkable details of anatomy were present in this specimen,” Polcyn said. “It really gives us a lot of clues as to how these things evolved and the timing of these characteristics.”

The team named the fossil specimen “Sarabosaurus dahli,” from the Arabic “sarab,” meaning desert mirage (a homage to the vanished seaway that left behind the Tropic Shale), the Greek “sauros,” meaning lizard, and “Dahl,” honoring volunteer Steve Dahl. Dinosaur naming has evolved from alluding to anatomical features of the animal—Triceratops, for example, meaning three-horned face—to pop culture references or anecdotes from the field, Titus said.

“We actually have several BLM employees now, myself included, that have had new things named after them from this area—this area is so rich with fossils, and we’re finding so many species,” Titus said. “If you want to come down and find me a new fossil or something, I’ll be happy to name it after you.”

Southern Utah, then, is now on the map as a place of distinction in the field of early mosasaur evolution. But the Tropic Shale is a goldmine for discovery in general, and one that paleontologists have only begun to comb through.

Albright said they expect to find more mosasaur fossils within the Tropic Shale now that they know what to look for. The Tropic Shale is a “dream come true,” he said, for finding early mosasaur fossils; Titus added that just last year paleontologists recovered nearly 15% of another mosasaur specimen.

“It’s a very unique corner of the world,” Titus said. “We’ve found 14 new species of dinosaurs from Grand Staircase since 2005, and it’s a very hopping place for looking for evidence of the past to reconstruct these ancient ecosystems. It gives us a very continuous look at ecology and ecosystem evolution through tens of millions of years of the late Cretaceous, leading up to the big extinction at 66 million years ago—the Tropic Shale is definitely taking a bigger role on the world stage in terms of understanding the Cretaceous in general and events leading up to the extinction.”

“All the pages in Earth’s history book are in this region,” Albright said: all within a few thousand meters are the remnants of the deepwater sea, the shallow beaches, and the inland swamps.

“I’ve worked in Mongolia and Antarctica, and I’ll tell you that you don’t need to travel hard to do some incredible, groundbreaking science: you can head to Southern Utah, and there are several lifetimes of paleo work right there,” he said. “It’s a wonderful part of the world, and we love what we do.”

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.