Some information may be outdated.

Evan Smiley, the Grand County Active Transportation and Trails (GCATT) operations coordinator, often hears the comment that his job maintaining the single-track trails around Moab must be easy: the trails are so in tune with the environment, so perfectly placed on rock ramps and between trees, that all the trail crew must do to maintain them is paint a few dots on the rocks. And maybe rake.

But no—what makes the trails so seamless is the skilled crew of trail builders GCATT hires each spring, summer, and fall. Grand County’s crew, today called the “Moab Trail Team,” has been developing and maintaining some of the most exciting, scenic, and challenging trails in the country—think Captain Ahab, or the Whole Enchilada—for years. Trails in this area are used by people all around the world, and GCATT cares for them through hiring the Moab Trail Team and Moab Trail Ambassadors, and through volunteer programs like “Maintenance Mondays.”

This past spring, one of the trail-building team’s main goals was to build trails for adaptive mountain bikes, bikes designed for riders with disabilities. Adaptive trails must have a three-foot wide clearance throughout the entire trail; according to Trailforks, six trails in Moab, mostly in the Navajo Rocks and Mag 7 areas, are fully adaptive.

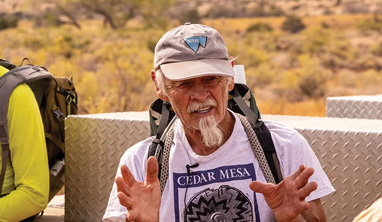

The spring team consisted of Smiley, Alex Mudler, Hannah Aguirre, Fred Wilkinson, John Sevier, Jane Pfaff, and Erik Johnson; many members of the team have worked on trails for years.

On a pleasant, cloudy day in May, the crew got to work developing Rowdy, a trail in the Horsethief area, as an adaptive trail. Many features of the trail, such as the ramps, didn’t meet the three-foot-wide threshold.

The team started with a ramp just a few hundred yards into the trail. They took apart the old ramp, then took stock of rocks in the area they could feasibly use to build a new feature. The team stayed close to the trail, finding rocks within a few feet of it to lighten their impact.

They try to be as minimally invasive as possible: they follow each other’s footsteps when going off-trail, move lizards out of harm’s way, and carefully position rock pulleys so as to not harm tree roots. In addition to maintaining the rockwork of the trail, the team also takes time to rake off-trail tracks.

“That’s part of our responsibility,” Smiley said. “If a trail user who doesn’t know the sensitive nature of the landscape sees tracks off-trail, maybe they’ll think, ‘Oh, that person did it, I can do it.’ Then it creates this group mentality. So [raking] is a big part of our job—it’s not glamorous, but it’s important.”

But most of the job is rock work, and specifically, working with sandstone. Sandstone can be tricky—it smashes more easily than other rock types, such as granite—but also satisfying—its relative softness means the team can sometimes chisel it into a proper shape, Smiley said. Putting ramps together is a mesmerizing puzzle, one that the team perfects down to the inch. They rely on each other’s ideas: the team will split apart to search for rocks, to plan out the ramp, and then come together again to slowly and carefully move rocks into place using a system of pulleys.

“This is a highly skilled crew,” Smiley said, “not to flex. But it takes skill to be able to learn all of this so quickly, to put rocks into place, to look at a trail and know what it needs.”

Another thing the team takes into consideration is how new features will hold up in the future: How will erosion in the area impact the ramp? Will it remain at the intended challenge level (green, blue, or black)? How often will a crew need to return to maintain it? Many members of the team this spring were mountain bikers themselves—Smiley joked that he has to stop himself from inspecting every rock feature on trails he bikes recreationally.

The team is off during June, but will return to work in the La Sal Mountains starting in July.

When a biker comes by, the team pauses the ramp-building to allow the biker to pass.

“Thanks for all that you do!” the cyclist says, biking happily away.

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.