Some information may be outdated.

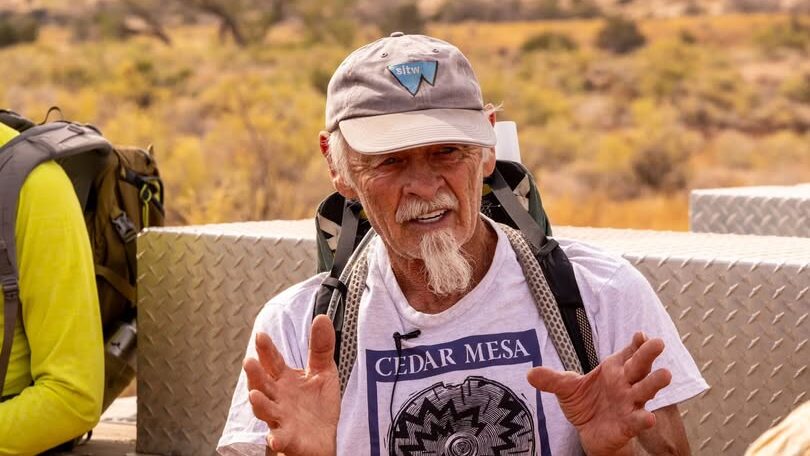

“Nights of Grief and Mystery,” a performance that explores life and death through music, storytelling, poetry, and ceremony, is coming to Moab on Saturday, Sept. 17 at 7 p.m. at Star Hall. The performance is created by author and activist Stephen Jenkinson and musician Gregory Hoskins.

The Moab Sun News chatted with Jenkinson further about what makes grief, especially in tight-knit communities, so important to talk about.

Moab Sun News: What differences have you seen in grief in small towns versus larger cities, if any? How have you seen communities grieve together?

Stephen Jenkinson: This is a bit of a generalization, but like so many generalizations, there’s a gem of absolute utter and merciless truth about it: Cities are places where there’s a degree of suffering that comes from the impersonal nature of the way of life. There’s too much of everything, and humans are not good at having too much of everything. Even grief is an impersonal kind in a large population center.

And again, this is a bit of a generalization, but I think it’s true that the kind of poetic and mythic fundamentals of citizenship are somehow more manifest and legible in a small population place. I live way out in the country myself, and so I’m not talking out of my hat here—I’ve really seen the kind of stuff I’m saying.

Moab Sun: In the past few years as a society, we’ve dealt with both cultural reckonings and COVID-19. Has your performance changed at all to reflect this new world we’re living in?

Jenkinson: I’ve been off the road about 36 hours—we just got home from 10 cities in 11 nights, doing a tour of England, Scotland, and Ireland. And the people there gave us a chance to find out what we know—I mean, the last time we played together as a band was in 2019. It’s one thing if you’re 25, and a couple of years skip past and then you’re 28. But I turned 68 years old in the time since I was last with the band, and 68-year-olds are not famous for being onstage and rocking out, as they say.

So we had the chance to watch ourselves in action and to find out whether or not the case that we were prepared to make, the pleas that we were prepared to issue, could lay claim to the attention span of a brutally overwrought people. I’m not saying everybody is in bad shape. But I am saying this: there’s no question whatsoever that the last few years have exacted a savage toll on people’s sense of well-being.

If you’re required to do something live in real-time, something that people can’t press pause, then you want to make sure that the times are recognizable in what you’re doing. Not that you’re somehow offering an alternative to, or a distraction from, the times. I think that is fundamentally irresponsible in a time as troubled as ours is.

We’re talking about the function of art here. And it seems to me that art is fundamentally prismatic, meaning, you know how a prism works—it takes something that’s allegedly transparent, like light, and when passed through a prism out the other side, its constituent parts become available to you in a spectrum of colors. So if you think of cultural life as that light, when you pass it through the filter of art making, what will come out the other side is not telling you everything’s going to be okay. Instead, you can begin to recognize the culture in all of its dynamics. You’ll want to know the rest of the story, not just the part that benefits you. That’s the mark of citizenship.

So you could say the Nights of Grief and Mystery are acts of a kind of radicalized citizenship. An artist’s fundamental responsibility is to be accountable to the times, not to reassure people that the times aren’t really as bad as they are.

Moab Sun: How do you think portraying the mysteries of life and death as a performance helps the audience to better receive the message?

Jenkinson: I don’t know if those two things go together necessarily. The word “helps” suggests that there’s this considerable upside that’s instantly recognizable and available. But the nature of art, as we were saying, is not linking arms and saying, “we shall overcome.” That’s political movements or religious movements, and I guess they have their place. The artistic obligation functions at the level of citizenship, not at the level of belief.

If you respect an audience, you treat them like grownups. You don’t pre-digest their food, which is what so much entertainment does—people feel reassured, but they haven’t been respected. I think respect is a more fundamental social responsibility than reassurances.

I’m not trying to quietly get anybody on my side. I’m not sure that I have a side. What I’m trying to do is to say, when finally there’s no hope, then what some people do is leave a little scent in the air of what they were willing to do in a time of trouble. The people to come, they’re going to need that: they’re going to need to know that they come from people who are worthy of coming from. You don’t try and hope to be worthy. You get worthy now.

I have a sense of urgency about this. Not desperation, but certainly urgency, for which I make no apology. And I don’t back off on it either. So is this for everybody? It should be. I mean, the questions about accountability and citizenship should be for everyone. But is that the same thing as saying that everybody’s gonna like it? Hell no. Everybody’s not gonna like it, just like a lot of people don’t like the mirror. What we do with this project is provide an opportunity for reflection.

Moab Sun: What about this performance or this message gives you, specifically, that sense of urgency?

Jenkinson: It’s an encounter of sorts—it’s an unexpected kind of encounter. It’s not a distraction, and so it’s not a commonly understood function or form of entertainment.

What we’re doing is so old that it’s unrecognizable to contemporary people. That’s why you can’t make a genre allocation for Nights of Grief and Mystery. What is it? Is it a musical? Is it poetry? Is it word slamming? Is it gospel? The answer is no, you’re wrong on all counts. Those things are relatively recent phenomena, but this thing that we’re doing, it’s fundamentally ceremonial.

If you’re engaged in ceremony, there are no audience members, and there’s no such thing as people sitting with their arms crossed waiting to find out what happens. The nature of a ceremony is everybody who’s there, the ceremony rests on their shoulders jointly. The tone of your participation determines the outcome as much as anything else.

If you believe that certain fundamental things are at stake in a time like this, and you’re willing to understand that the outcome of an event like this is a shared one, suddenly, we’re in something that’s much closer to a village than we are in a pseudo, “me first” democracy like the one that currently prevails.

You asked me where my sense of urgency comes from. Partly it’s that I’m not a kid, so I’m a little captivated by the understanding that time is rapidly slipping through my fingers. I should say that this makes it sound like there’s no humor in the show, or there’s no sense of camaraderie, which is completely wrong—there’s tons of that kind of thing, but there’s also a place for it, and that place is an attempt to articulate the notion of what a village-minded approach to a very troubled time could possibly be.

Nights of Grief and Mystery is a child of its time. It’s not a grandfather wagging its finger—it’s a child of its time, and it belongs to this time. So yes, I have a sense of urgency, and it compels me. But I’m not stupid and think that everybody is similarly compelled. This is why you have a guy on stage behind a microphone who’s making noise: not everybody’s doing it. It’s not a party. It’s not a democracy. It’s something else. It’s an old ritual of conjuring, simply through the consequence of the word, the gesture, and the rhythm.

MSN: Is there anything else you want to add?

Jenkinson: We, the band, consider ourselves several things at the same time: responsible; lucky; charged with a sense of purpose; non-tyrannical; treating people with genuine regard, but at the same time, not leaving them alone.

I used to work in what I call the death trade, and I did that for long enough to have learned some gruesome lessons about what people are willing to ignore for the sake of just getting by. But when you’re in a time when death is now your companion and not your enemy, then you have a different orientation to these kinds of challenges.

So is it not possible, then, that the time we’re in is some kind of early stage announcement of the proper and necessary undoing of our way of life? Aren’t there enough indications that our consuming way of life is utterly unsustainable? Of course. Un-sustaining, too. If we don’t course correct in a radical fashion, what will your kids’ generation possibly see when they look back on this very time? That’s the filter, the lens, that the Nights of Grief and Mystery is proceeding with: what will this look like in two scant generations from now?

We’re in a time of short strokes and details, not broad masterplans. We have to earn our keep in a time like this. We have to earn whatever regard we might get when we become ancestors, when we’re no longer alive, when we join the ancestral parade. Will anybody claim us? Will anybody want to be from us?

The audiences we’ve performed to already, they’re absolutely rapturous. So how do you explain rapture as a response to very firmly delivered sense of foreboding? I think the answer is that if you treat people with genuine respect in your performance, and you don’t lie to them, it’s such an unusual experience for an audience now. They don’t know what to make of it at first—they’re used to filtering, they’re used to being jaded. So when somebody stands in front of them and is not trying to sell them, they don’t know what to do with it initially. But by two hours later, at the end of that, they feel recognized, and they’re immensely grateful for the recognition. So I’m proud of the Nights of Grief and Mystery that seven years down the pestilential road, we’re better at this than we’ve ever been.

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.