Some information may be outdated.

The Moab Mosquito Abatement District recently secured funds to support a citizen science project to monitor mosquitoes, and the district is inviting interested Moabites to a workshop on June 22 at the Grand Center from 5 to 6 p.m. to learn how to participate.

“The date of the training actually coincides with National Mosquito Control Awareness Week (June 19-25) so I thought that was good timing,” said Michele Rehbein, who is leading the project. Rehbein was until recently the manager of the Moab Mosquito Abatement District; she accepted a position with another mosquito abatement organization in the Salt Lake City area, but has arranged to continue managing the grant, and will travel to Moab as needed to facilitate the citizen science project as well as other outreach efforts.

The funding—$49,990 for outreach, education, and the citizen science project—comes from the Western Integrated Pest Management Center, which is funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture “to promote smart, safe and sustainable pest management to protect the people, environment and economy of the American West,” according to the organization’s website. In addition to the citizen science project, Rehbein hopes to use some of the funding to expand the district’s website and potentially create an educational video about mosquito protection and prevention.

The citizen science project will focus on monitoring for the Aedes aegypti species, which can carry viruses and diseases including West Nile, dengue fever, chikungunya, and Zika virus. The species was identified for the first time in Moab in 2019, and was detected again in 2021. Because the species poses a serious public health risk, the district wants to be proactive in detecting and reducing or eliminating them locally, and preventing them from spreading elsewhere. If a breeding habitat is identified, larvicide can be used to treat a small area to prevent immature mosquitoes from growing into biting adults. Fogging with chemicals to reduce adult mosquito populations is a last resort: it can have undesirable effects on nontarget species and is unpopular with residents, but mosquito managers see it as the lesser of two evils: better to fog when the species is detected and before it’s well-established, than to have to deal with an entrenched population that could carry serious diseases. [See “Mosquito season winds down,” Oct. 7, 2021 edition. -ed.]

Early detection is key to avoiding fogging, and that’s one reason Rehbein is excited to get the community engaged in monitoring and understanding the life cycles of mosquitoes.

“We have such a small crew,” Rehbein said of the MMAD. It’s hard for technicians to regularly check all the possible places that mosquitoes can breed. Having property owners monitor their own yards will allow the district to gather more data, some of it from sites where they haven’t had traps in the past.

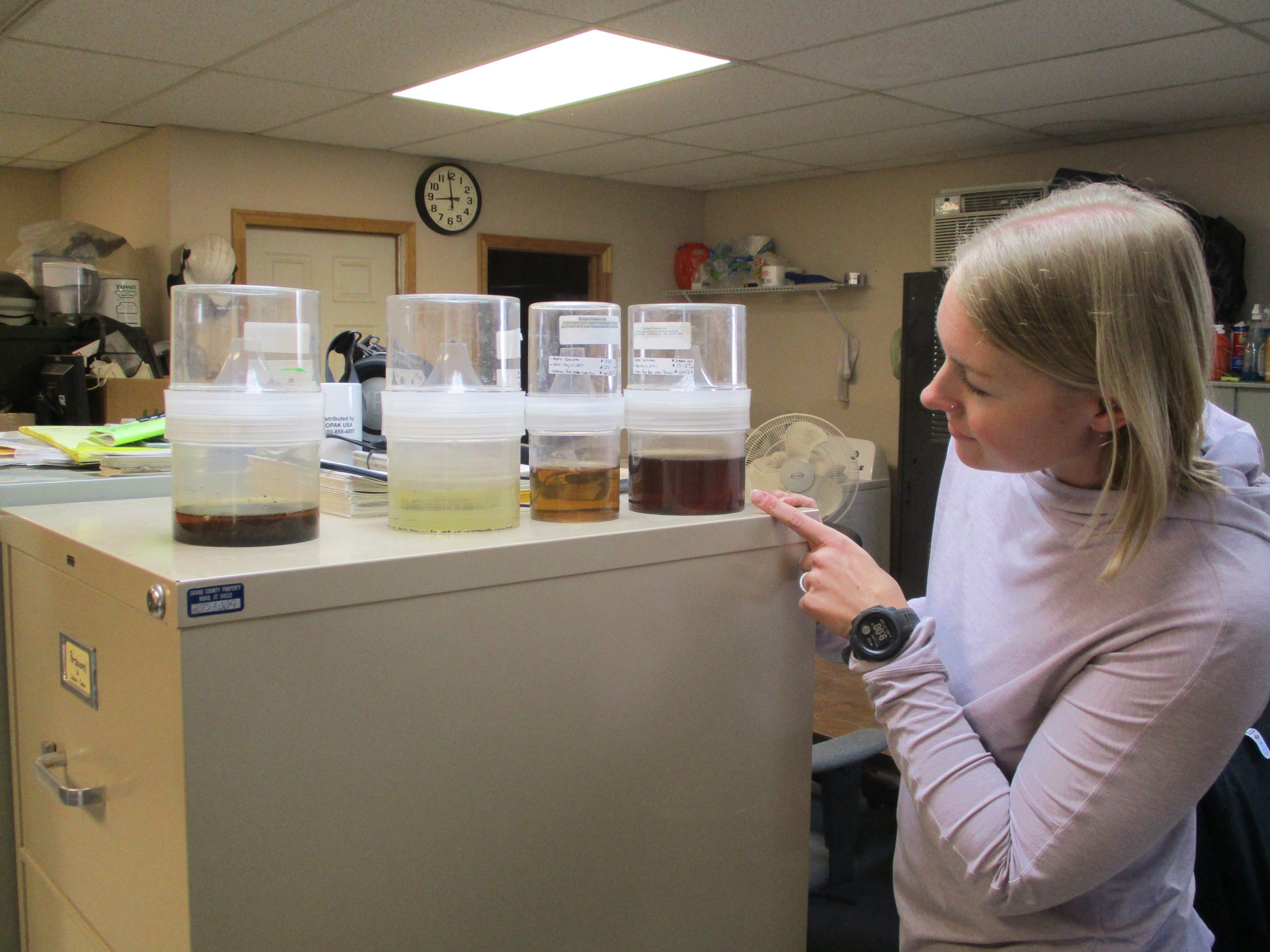

Participants in the citizen science project—called the Moab Mosquito Project—will use a device called an ovitrap to monitor mosquitoes. It’s a simple trap: a plastic cup painted black, filled partway with water, and garnished with a popsicle stick or other substrate where mosquitoes might lay their eggs. Aedes aegypti are a container mosquito, meaning they like to lay their eggs in small pockets of standing water: environments like the ovitraps. MMAD staff will collect any mosquito eggs found in the traps and identify them in the lab.

Rehbein hopes that in addition to helping the district and reducing mosquito populations, the Moab Mosquito Project will also get people interested in science and management practices.

“I want people to enjoy themselves and have fun while also learning and being involved,” she said.

Aedes aegypti will breed in any small container: a birdbath, pet dish, or old tire after a rainstorm. Another focus of Rehbein’s project is to spread awareness of how to prevent mosquito infestations. Pet dishes, drain trays for plants, and birdbaths should be regularly emptied, scrubbed, and refreshed, and other containers that might hold standing water should be emptied and cleaned frequently, removed, or covered. Indoor containers should be monitored as well, as Aedes aegypti has adapted to thrive inside in the right conditions. These steps can help keep Aedes aegypti populations low, to prevent the district from having to consider spraying insecticide.

Rehbein has already been engaged in community outreach in Moab over the past couple of years. She partnered with the School to Science program of nonprofit Science Moab to get high school students into the field, learning about scientific research and mosquito management practices. [See “High school students collect valuable data and explore careers,” May 12 edition. -ed.] She has also participated in the Moab Festival of Science to connect with residents and visitors and explain the district’s mission, and presented through Science Moab’s Science on Tap. [See “Local mosquito researcher will present at last Science Moab on Tap,” Feb. 4 edition. -ed.]

Rehbein said the workshop will include some background on the district, a primer on mosquito biology and the species that are found in Moab, information on mosquito prevention, and how to make and monitor an ovitrap. Materials will be provided and the workshop is free.

“This can be a fun family friendly project and all ages can be involved,” Rehbein said.

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.