Some information may be outdated.

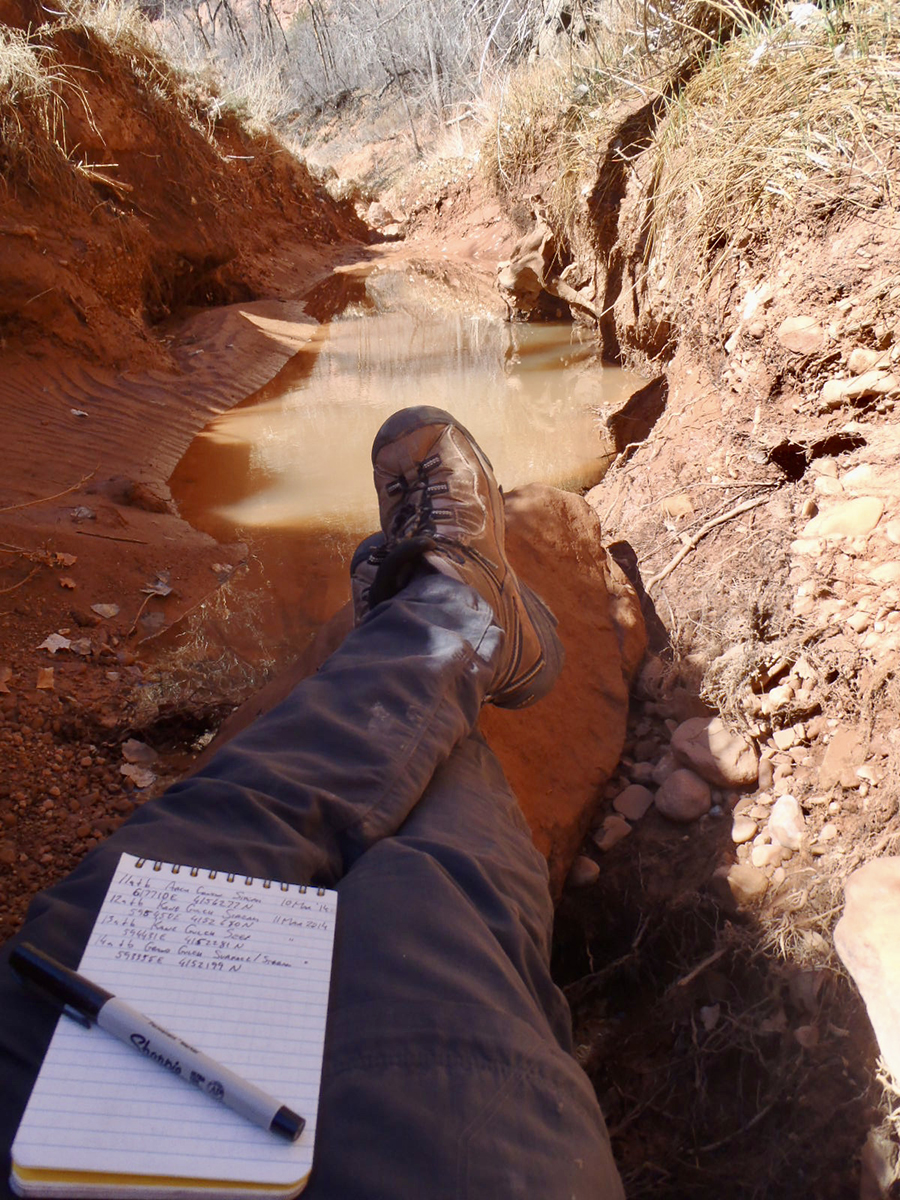

When R.E. Burrillo, an archaeologist and author with a focus on the Bears Ears region, was 18, he left his home in upstate New York with dreams to become a writer. He found himself in New Orleans, Glacier National Park and eventually, the Grand Canyon and Zion National Park. It was in those two places where he discovered the wonder and glory of Colorado Plateau archaeology for himself.

“We’re not really raised in the northeast to think that exploration is even a thing you can do anymore,” he said.

“In the Grand Canyon region, you just go hike, slip down some cliff as safely as possible and come around a corner and there’s something that’s 800 years old and it’s intact,” said Burrillo. “There’s no signs, there’s very little damage from looters, and it’s just there as part of the landscape. That’s not even conceivable where I’m from.”

Burrillo said he found his true calling in Bears Ears, an area he was drawn to in 2006. He’ll give a presentation called “Farming High & Dry: What Chemistry and Collaborative Archaeology Reveal about Agriculture in Ancient Bears Ears” on Tuesday, Jan. 11 at the next “Science Moab on Tap” event at Spitfire Smokehouse (2 S. 100 W).

So, what do chemistry and collaborative archaeology reveal about agriculture in Ancient Bears Ears? What the chemistry aspect gives us, Burrillo said, is a minimally invasive, non-destructive way to reconstruct past actions and past behaviors.

“Traditional archaeology is a very destructive practice,” he said. The question of “how are people living here?” was answered by digging everything up and running it through a mass spectrometer.

“And of course, that dissolves it into dust,” Burrillo said. The way forward for archaeologists who want to continue their research ethically is to find these non-destructive ways to interact with historical objects.

In his talk, Burrillo will discuss the importance of water chemistry, which allows archaeologists to rebuild what was going on in the surrounding environment at the time—“we’re not going out and digging up really anything, not monkeying with anyone’s ancestor’s skeletal materials or anything like that. We’re just looking at plants and drawing a picture,” he said.

The second aspect of Burrillo’s talk is his use of “collaborative archaeology” in his research, which he describes as simply talking to people, especially when his research concerns Indigenous cultures. An issue that the archaeology field has historically suffered from, especially in the United States, is that it’s a science conducted almost exclusively by Euro-American people who are looking at, investigating, and trying to interpret the material records of almost exclusively Indigenous people, Burrillo said.

“Even with the best you can do to be as nice and moralistic and ethical, that’s going to be problematic right out of the gate,” he said. “The two ways around that are to one, stop doing it and just investigate something else; or two, start breaking down that demographic makeup.”

Instead of talking about the “vanished peoples,” and trying to reconstruct their history “as if they had somehow gotten into a rocket ship and disappeared,” Burrillo said, archaeologists should push themselves to find the living relatives of those populations and talk to them.

“It’s supposed to be a humanistic science,” he said. “Talk to people. Involve Indigenous perspectives. You’ll get some good answers that way.”

Kristina Young, the founder of Science Moab, said the “on tap” events are meant to bring together the Moab community with scientists who work in the landscape that Moabites call home. There is a lot of fantastic science being done here, she said, but too often that science is locked behind the paywall of a science journal, or is hard to understand. Science Moab’s goal is to make that science accessible.

“I’m really excited to hear what [Burrillo’s] learned about farming in Bears Ears, and how and where farming was happening and what that landscape looked like in the past,” she said.

As for what’s next for Burrillo: he’s working on another book.

Burrillo’s book, “Behind the Bears Ears: Exploring the Cultural and Natural Histories of a Sacred Landscape,” came out in October 2020, in the midst of the pandemic and of the U.S. presidential election. The book did “remarkably well” despite those distractions, Burrillo said, but it left him wanting more: the book was streamlined, meaning there were important sections that had to be cut from it, and most importantly, Burrillo didn’t have the chance to connect with the people who wanted to read his work.

“So that just immediately boiled straight over into this idea of, ‘why don’t we put out basically a B-side album?’” he said.

His second book will be published sometime this summer, and will discuss more of Burrillo’s personal connections to Bears Ears—including a chapter on why he left upstate New York—and will be “a little bit more behind the scenes,” he said.

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.