Some information may be outdated.

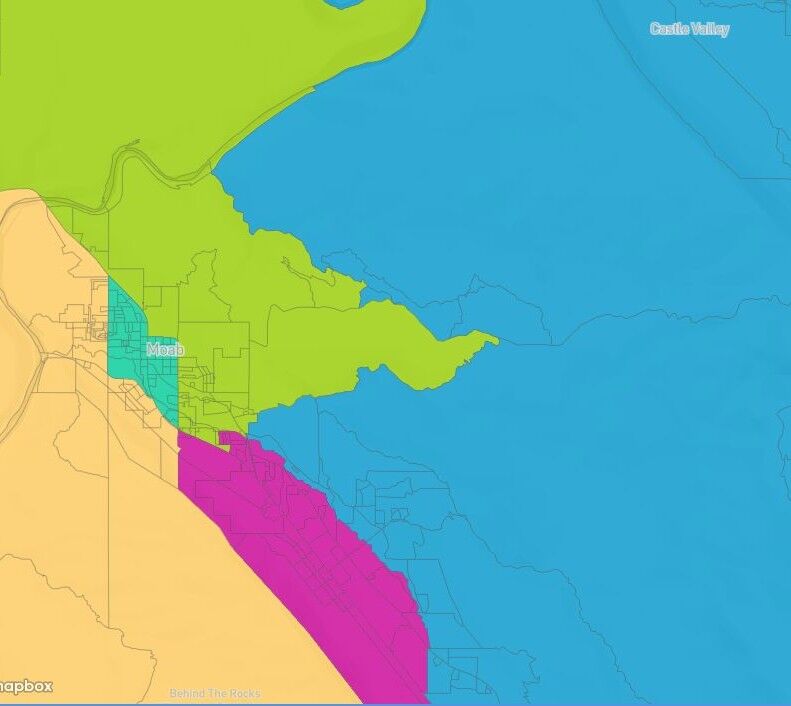

The Grand County Commission hopes to select the final boundaries of new county commissioner districts by mid-December. At a Nov. 30 workshop, commissioners narrowed map options down to two possible choices, and will look at them again at their next meeting. The body has been working on the process of redrawing voter districts in the county for months, parallel to the state process that recently produced new districts for the state legislature and school board as well as for Utah congressional representatives. Commission Chair Mary McGann was absent from the workshop.

Redistricting is supposed to happen every 10 years, after the national census. For unclear reasons, Grand County districts haven’t been redrawn since the early 1990s. Shifts in population distribution mean the districts are now very unbalanced; also, District 3 is broken into two non-contiguous parts, which is counter to a guiding principle of drawing reasonable and fair district boundaries.

The responsibility of defining new boundaries falls on the commission, but county leaders wanted to ensure they heard views from the public. This summer, the county launched an online portal for community comments and map submissions. Anyone can use the platform’s map-drawing tool to create a map for consideration, or submit written comments or suggest “communities of interest” that should be kept together within a district. The portal is still open and can be reached by clicking the “Redistricting 2021” tab at the top of the county’s main webpage, grandcountyutah.net.

Several rules and guiding principles direct the making of voting districts. Populations within each district must be close to equal, varying by no more than 5%. Districts should be contiguous and compact, respect neighborhood boundaries and communities of interest, and not be drawn in a way advantageous to one political party. Five of Grand County’s seven-member commission seats are elected by district, and two are at-large seats, so commissioners must create five districts that will be used for commissioner seats, school board districts, and voter participation areas for county referendums.

On Nov. 15, the commission held a workshop to evaluate the few dozen maps that had been submitted through the portal. Specific questions surfaced as commissioners looked through the maps: Should all the rural, ‘outlying’ areas of the county be grouped together, or put into different districts? How should incorporated and unincorporated parts of the county be combined or split? The neighborhood around Holyoak Lane, at the south end of Moab, proved difficult to conveniently place in one district or another. The commission narrowed the map options down to nine candidates to consider at the Nov. 30 workshop.

“There’s a lot of different things you can try to accomplish with a district map, and it’s impossible to get an ‘A plus’ on all of those,” Commissioner Kevin Walker said at the workshop. Walker has taken a lead role in advancing the redistricting process. He explained that some of the desired qualities of district boundaries may conflict with each other: clean lines following logical features (like streets or creeks) for divisions, keeping neighborhoods and communities of interest together, and maintaining population balances.

“There’s lots of ways of slicing up the population of Grand County, and one can assess a district map from all those different points of view and you’re never going to be perfect by all those different yardsticks,” Walker said.

Walker also pointed out that the population numbers used to balance the districts are those given by the US Census Bureau following the 2020 census, which is standard practice in creating district boundaries. Those numbers count people, not registered voters, so even if the districts are perfectly balanced by population, the number of voters in each district could be very different. Another issue with balancing populations is the potential for growth in each district. The Spanish Valley area is poised for substantial growth in the near future, with the Arroyo Crossing subdivision planning almost 300 new housing units and several developments planned under the county’s High Density Housing Overlay located in Spanish Valley.

Commissioners discussed the issues that had been identified at the previous workshop. Regarding areas of the county that aren’t part of the Moab population center—Castle Valley, Castleton, Thompson Springs, and suburbs of Green River—commissioners were split on whether those areas should all fall into the same district or be separated. Walker referred to comments from Castle Valley citizens who said they felt more in common with rural areas of Spanish Valley, south of Moab, than with the other outlying areas of the county. Commissioner Gabriel Woytek said it made more sense to him to keep the rural areas in one district. Commissioner Evan Clapper said he was neutral on the issue, but added,

“I know there’s been times when there’s been a strong ‘rural’ voice on the commission… I don’t want that voice to be lost.”

Commissioners agreed on another issue in question: whether Spanish Valley should be divided on a north/south or east/west boundary. All at the workshop agreed that an east/west boundary made more sense.

The Holyoak neighborhood was a sticking point in discussions. It lies south of Moab; it’s outside the incorporated city, but has a different character and feel than the Spanish Valley area just to its south. It’s densely populated and is at the intersection of districts in most of the maps that were submitted.

Walker highlighted the difference between incorporated areas, like Moab City and Castle Valley, and the unincorporated county: unincorporated areas are subject to the planning and zoning decisions of the commission. Those decisions can affect things like housing density and commercial activity in neighborhoods. Castle Valley and Moab make their own planning and zoning decisions.

In being unincorporated, the Holyoak neighborhood is similar to Spanish Valley to its south; however, some commissioners noted that with its high density and proximity to town, in character the neighborhood is more similar to districts to its north. Because the neighborhood is populous and lies on a logical break between districts, it’s hard to keep it all together without prompting a need to split neighborhoods elsewhere on the map.

In other areas, census block boundaries split neighborhoods in awkward ways. Census blocks are the smallest units used by the United States Census Bureau in recording population data. They may be delineated by features such as roads, streams, and railroad tracks, or by boundaries such as property lines, cities, county lines, or school districts. Census blocks are used in the mapping portal tool, but they don’t have to be used for the final district boundaries. For example, on 200 North, the census block boundaries split the north and south sides of the street, but as a neighborhood it makes sense for the houses on the north and south sides of that street to be in the same district. The commission may tweak the district boundaries to bring those residences into the same district.

The commission agreed on two maps to consider further, called “Contiguous neighborhood plan” and “Rural zones divided plans-variant 1.” They can be viewed and commented on through the portal tool. The commission may make further alterations to the maps and will choose a final map at their regular meeting on Dec. 7.

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.