Some information may be outdated.

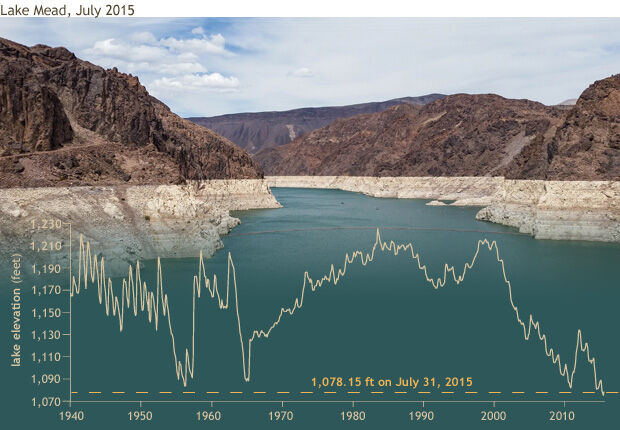

The two largest reservoirs in the country, Lake Mead and Lake Powell, have dropped to historic lows this summer. Boat ramps are dry and huge “bathtub rings” circle the canyons of the reservoirs. Managers fear the water in Lake Mead could drop low enough to force the shut-down of the hydroelectric power plant powered by the reservoir, which serves close to 8 million people in Nevada, Arizona and California.

Those low reservoir levels are one indicator of a major problem: the Colorado River, which feeds those lakes, is overallocated. On Aug. 16, the Bureau of Reclamation announced that recent lake measurements have reached thresholds that trigger conservation measures outlined in management agreements reached in previous years. Those cuts may be only the first of many if drought conditions continue; water activists say the cuts are too little, too late, and they’re calling for more drastic action.

Background

Powell and Mead are fed by the Colorado River, called “the hardest-working river in the west” because it serves the needs of over 40 million people. Agriculture, urban use, and river ecosystems rely on its flow. Allocation of Colorado River water is governed by “the Law of the River,” a complex set of laws and agreements among the seven Colorado Basin States: Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, Arizona and California. Drought, climate change, growth and development, and inflated estimates of the Colorado River’s flow used in early agreements have strained the parameters of the Colorado River Compact, the central element of the Law of the River.

Managers, scientists, activists and users have anticipated the need for adjustments to the agreement and increased conservation measures. In 2007, a set of “interim guidelines” were drafted to direct the allocation of Colorado River water in the event of a shortage. In the following years, it became clear that plans would be needed for even drier conditions than provided for in the interim guidelines; in 2019, stakeholders agreed to a Drought Contingency Plan that outlined steps for even lower thresholds.

On Aug. 16, the Bureau of Reclamation announced the results of the August 2021 24-month study of the Colorado River. The bureau’s 24-month studies, updated monthly, use past and current data and computer modeling to predict future reservoir conditions, dam operations, and inflows and outflows. This information is used to guide operational policies.

The August 2021 24-month update triggered a set of actions defined in the 2007 interim guidelines and the 2019 Drought Contingency Plan: extra water will be released into Lake Powell and Lake Mead from upstream reservoirs, and Colorado River allocations to Lower Basin states will be cut.

Dire numbers

The Aug. 16 Bureau of Reclamation press release outlines the current extreme conditions of the Colorado River system.

“The Upper Basin experienced an exceptionally dry spring in 2021, with April to July runoff into Lake Powell totaling just 26% of average despite near-average snowfall last winter,” it reads. “The projected water year 2021 unregulated inflow into Lake Powell—the amount that would have flowed to Lake Mead without the benefit of storage behind Glen Canyon Dam—is approximately 32% of average. Total Colorado River system storage today is 40% of capacity, down from 49% at this time last year.”

Representatives from the Bureau of Reclamation, along with representatives from water authorities in the Colorado River Basin states, held a virtual press conference on Aug. 16 outlining the new conservation measures. Bureau officials acknowledged the hardship of reduced river water allocations being shouldered by the Lower Basin states, and reviewed the careful monitoring and collaborative agreements that shaped the conservation measures. They emphasized their reliance on the best available science and their commitment to sustainable management of the river.

“The announcement today is a recognition that the hydrology that was planned for years ago, but we hoped we would never see, is here,” said Deputy Commissioner for the Bureau of Reclamation Camille Touton at the start of the press conference.

“At the heart of today’s announcement is also the acknowledgement of the hardship that the drought has brought to people across the basin states, to our tribal communities, and to Mexico,” Touton went on. “The impacts of this drought are to our colleagues, to our neighbors, to our friends—but it doesn’t just impact the communities that we serve. It impacts the community that we call home. My hometown is in the basin.” She recalled visiting the Hoover Dam around the turn of the millennium, and seeing the water level so high it seemed as though she could reach down and touch it—a stark contrast from today’s conditions.

The cuts

According to the 2007 interim guidelines and the Drought Contingency Plan, the reservoir levels identified in the August 2021 24-month study trigger the “mid-elevation release tier” for Lake Powell, meaning that in 2021, Lake Powell will release 7.48 million acre-feet in water year 2022, down from 8.23 million acre-feet released in water year 2021. Lower Basin states will receive reduced Colorado River allocations: Arizona will take an approximately 18% cut of 512,000 acre-feet; Nevada will take a 7% cut of 21,000 acre-feet, and Mexico will take a 5% cut of 80,000 acre-feet.

The agreements don’t specify where or how states will cut or make up for those reduced allocations. Representatives from Arizona and Nevada discussed some of the preparations and measures their states have taken or are considering. Mexico did not have a representative at the press briefing.

John Entsminger of the Southern Nevada Water Authority said Nevada has been preparing for water shortages for decades.

“Nevada has invested nearly $1.5 billion in new infrastructure to protect access to our primary water supply,” he said. “We’re managing one of the nation’s largest and most comprehensive water conservation programs. At the forefront of that program is our ability to sustainably recycle all of our indoor water use.” He added that Nevada had recently entered into a partnership with California to develop a large-scale water recycling program.

“We must adapt to the reality of a warmer, drier future,” Entsminger said, enjoining all Colorado River users to use creativity and collaboration to face that future.

Thomas Buschatzke, chair of the Arizona Water Banking Authority, said the cuts in his state will largely affect farmers. Arizona has programs to help farmers drill wells to access groundwater to make up for some of the cuts, but Buschatzke acknowledged it will be a significant burden on those people. He said the state also has a robust water recycling program, and is developing ways to expand the uses of reclaimed water.

Upstream reservoirs release extra

Reservoirs in the Upper Basin will release extra water to ensure safe levels are maintained in Lake Powell and Lake Mead. Flaming Gorge Reservoir, which straddles Utah and Wyoming, will release an extra 125,000 acre-feet. Blue Mesa Reservoir in Colorado west of Gunnison will contribute 36,000 acre-feet. Navajo Reservoir, on the border between Colorado and New Mexico, will release an additional 20,000 acre-feet.

Increased releases from reservoirs upstream will have impacts at those sites as well. According to a July 30 news release from the Curecanti National Recreation Area, which contains Blue Mesa reservoir, the lake will drop about two feet per week through August, September and October.

“As a reminder, Blue Mesa’s full pool elevation is 7519’. On July 29, the reservoir elevation was 7457’. This is 62’ below full pool,” reads the press release. “By the end of October, it is predicted that Blue Mesa will be at 7423’ or 96’ below full pool.”

The news bulletin warns visitors to use caution at the edge of the reduced reservoir.

“Muddy and unstable banks may create hazards,” it says. “Do not drive or park near the mudline and be aware that there may be hidden soft spots throughout the area. If you get your vehicle stuck out there, you are responsible for your own recovery.”

The press release gave thresholds for when boat ramps in various locations would be closed. On Aug. 17, Curecanti announced that Elk Creek marina concessions would close on Aug. 22, and ramps at Elk Creek and another section of shoreline would temporarily close on Aug. 23 while docks are moved and anchored in deeper water.

The news release also warns of the potential for cyanotoxins, which are produced by algae and can be poisonous to animals and humans.

Activists respond

Later on Aug. 16, the same day as the Bureau of Reclamation’s press briefing, a coalition of water activists led by Kyle Roerink of the nonprofit Great Basin Water Network held their own virtual press conference in response. Activists on the call said the bureau is using outdated science to make its predictions, and therefore getting surprised by foreseeable conditions. They said the bureau is being reactive rather than proactive; they called for water managers to use the most current science to model expected river conditions and plan based on those numbers; and pushed for a moratorium on water development infrastructure projects like the contentious Lake Powell Pipeline slated to be built to draw water from Lake Powell to serve rapid growth in Washington County in Utah.

Roerink called the bureau’s remarks “predictable,” and admonished, “We need actions that speak louder than words.”

“This is not the time for small steps, this is the time for large ones,” agreed J.B. Hamby, vice president of the board of directors for the Imperial Irrigation District in California. He said urban development was proceeding in a reckless manner at the expense of rural and agricultural communities.

“Rural agricultural communities are not reservoirs of water to be drained to continue relentless, reckless, and unsustainable sprawl in large urban centers throughout the desert southwest,” Hamby said. “They’re communities that have worth and value and need to be able to survive and thrive too.” Participants on the call derided plans for large developments in southern Nevada and other urban centers in the Southwest, saying they haven’t adequately planned for water to serve those developments.

The Lake Powell Pipeline, in particular, is an object of frustration for water activists, who say it makes no sense in consideration of current conditions in the Colorado River Basin. They fear pipeline proponents will continue to push the project through in spite of objections. Earlier in August, Roerink drew attention to amendments to a federal infrastructure bill proposed by Utah Senator Mike Lee that would have allowed federal regulatory agencies to authorize states to take on oversight of large-scale water projects like the Lake Powell Pipeline. The amendments failed, but water watch-dogs are on the alert for efforts to push through the project without transparency and honesty.

Moab’s John Weisheit, founder of the nonprofit Living Rivers and Colorado River Keeper, weighed in on the idea of a moratorium on new water development projects.

“More projects like the Lake Powell Pipeline is not how you solve this crisis,” Weisheit said. “You do it with green infrastructure, you do it by working with nature, rehabilitating nature to improve the yield of the Colorado River, not only for surface water but for aquifers.” He noted that aquifer water, once depleted, takes millenia to be renewed.

While the bureau repeated its reliance on the best available science, activists said that’s not how the bureau is actually operating. Zack Frankel, executive director of the Utah Rivers Council, said robust science predicted a much greater drop in Colorado River flows by today than the Bureau of Reclamation predicted, and the bureau’s estimates indeed turned out to be too conservative.

“The Bureau of Reclamation’s been in denial,” said Frankel. “And that needs to end, because they’re just sitting back and using ten-year-old climate forecasts that were way off.” He said current plans don’t address the extent of decreased flows that’s predicted by reliable models.

“The federal government has no plan to deal with these dropping levels,” said Frankel. “The drought contingency plan is only a reservoir management plan; it is not a climate adaptation plan.” Frankel compared the reservoirs to a savings account. Managers are making changes to how those “savings accounts” are used, Frankel said, but ignoring the fact that income—that is, natural inflow to the river system—is dropping.

“If one loses their job they can run around to every bank in town and create a new savings account, but they’re not going to get rich,” said Frankel. “What we have is a problem of reduced income as a function of climate change shrinking our snowpacks.”

In closing the press conference, Roerink echoed Frankel’s point.

“Back when the 2007 interim guidelines were being developed, the Bureau of Reclamation was predicting that Lake Powell’s elevation would be 100 feet higher than it is today,” Roerink said. “That’s how screwed up things are.”

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.