Some information may be outdated.

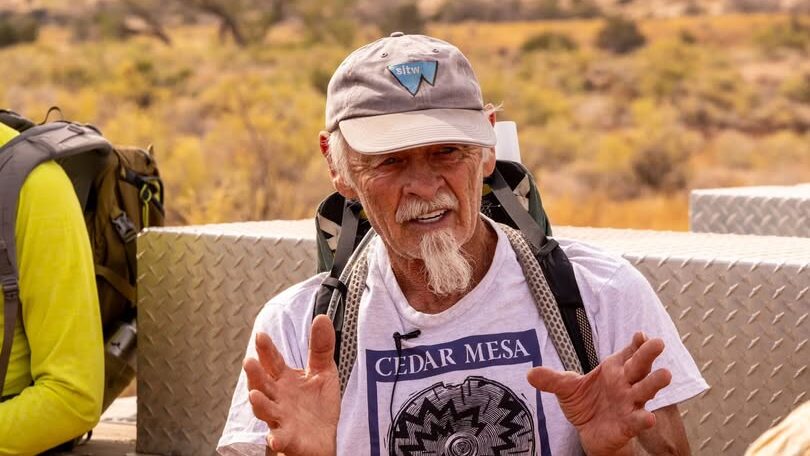

As a nationally- and internationally-renowned climbing spot, the Indian Creek area outside of Moab is home to stellar natural beauty, world-class crags…and increasing recreational use. This week, Science Moab speaks with David Carter, an avid climber and assistant professor of public policy and administration at the University of Utah. We discuss the beauty of Indian Creek, its role within the climbing community, and some sociological tools for encouraging the conservation of climbing areas.

Science Moab: What are you seeing in how people are interacting with popular climbing areas? What are you studying?

Carter: We’re seeing a lot of dispersed recreation these days and increasing user numbers. It’s a general trend towards more and more folks visiting climbing areas and recreating in areas that are environmentally vulnerable and ecologically rich. We’re seeing a lot of impacts from those increasing user numbers.

Perception is often reality for these climbers: if they don’t think that there are a lot of impacts in the climbing area, they’re not going to see them, even if the impacts are there and measurable.

So we try to understand, what are climbers’ perceptions of the areas they recreate in? What did they say they’re more or less likely to be moved by when it comes to adhering to certain rules? We use those data to develop palatable management systems that climbers can rally behind. We need to understand the best ways to encourage self-regulation within the community.

Science Moab: What makes climbing areas different from busy hiking or biking trails?

Carter: For climbers, you can’t just put in more crags in climbing areas; there has to be the rock to do it. So one difference is the nature of the resource limitation compared to other outdoor dispersed recreation amenities.

Another difference comes back to the nature of the climbing community itself. It’s changing, and changing rapidly, in some good ways and some not-so-good ways. But historically, climbing is what sociologists refer to as a lifestyle sport. There’s a heavy tradition of self-regulation in the community. That tradition carries over as we try to sustainably manage these areas, in some good ways and in some bad ways. Part of that culture has also been this idea that climbers are rebels, which is not helpful when we’re trying to institute rules to protect a resource. So there are some aspects of that culture we’re trying to change.

Science Moab: Your paper described something called “common pool resource theory.” What is that and how is it used?

Carter: “Common pool resource theory” is a theoretical framework that lots of social scientists will use to understand what we refer to as collective action problems. The basic idea is that a common pool resource is an open-access resource. But it’s depletable, so when people use that resource, there’s less of it to go around for other users. It’s a basic governance issue.

For folks misusing an area, the cost to them individually is small or nothing. But it’s a cost borne by everybody who uses and cares about the area. So how do we get folks to behave in ways that may be costlier to them, but that will benefit everybody?

Science Moab: What sort of data do you collect?

Carter: I mostly do surveys and studies of climbers themselves, their perceptions, and their perceived behaviours, their reasons for doing things. For me, this takes the form of surveys on what climbers do, what they perceive, and what they care about. I want to understand what I think of as the institutional landscape of the community. What does the community care about? What did they pay attention to? How much variation is there? Where is their agreement within the community?

Collectively, we should be combining that with data from the natural sciences, understanding the landscapes, to ensure sustainable use. Both data sources are needed to have any kind of effective management system.

Science Moab is a nonprofit dedicated to engaging community members and visitors with the science happening in Southeast Utah and the Colorado Plateau. To learn more and listen to the rest of David Carter’s interview, visit www.sciencemoab.org/radio. This interview has been edited for clarity.

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.