Some information may be outdated.

Jeff Gutierrez bought five acres in the foothills of the La Sals about five years ago and built an off-grid yurt where he often stays during some parts of the year. The risk of fire was one initial consideration in the project, but as the worsening drought made itself apparent about a year after he bought the property, his concern heightened.

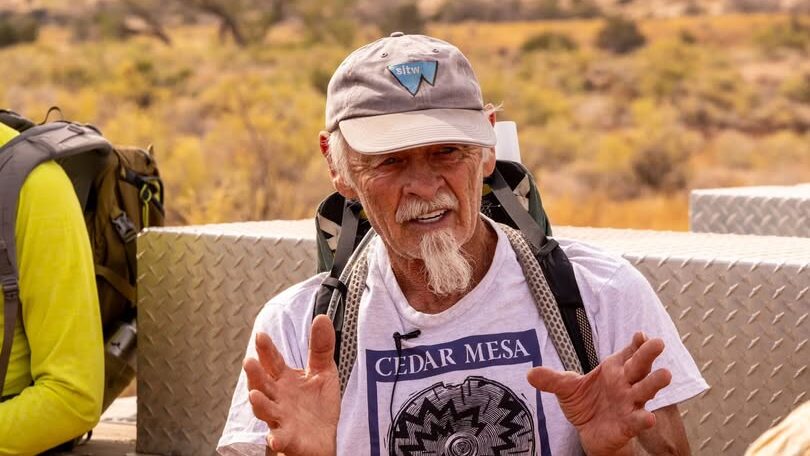

“I noticed all the piñon trees were dying off on the hillside,” he said. “Ever since then I’ve been really aware of the fire danger up there.”

That risk manifested last month when the Pack Creek Fire ignited less than two miles south of his property, quickly intensifying to a crown fire that destroyed 10 buildings in the Pack Creek subdivision and went on to burn thousands more acres higher up in the mountains. Gutierrez recounted his experience preparing for the possibility of fire and watching it become a reality so close to the structure he’d built himself.

The day the fire began, Gutierrez was enjoying a few hours cooling off by the river after finishing a day of work with a local landscaping company. He had to get back to town in the late afternoon to teach a saxophone lesson, and when he got into cell service, he saw several texts and a missed call, and the phone was ringing with a call from a friend. He answered.

“Dude, Gutierrez, is your yurt on fire?” the friend asked. The smoke plume was visible from most places in town, though not from the River Road, and people familiar with the La Sals could see that it looked close to homes.

Gutierrez began an apprehensive drive toward town.

“It felt like it took forever,” he remembered. As he drove he mentally searched his property for anything that could have somehow ignited the fire, a possibility that has often given him anxiety. Could wiring on his solar panels, or a random bit of glass focusing the sun, have been the cause?

“That’s what I was freaked out most about,” he said. The cause of the fire, officials later reported, was an abandoned campfire in the Pack Creek picnic area.

As he neared Ken’s Lake he could see that the fire was mostly in Pack Creek, south of his property. The wind was blowing hard towards the yurt. He followed the loop road towards his place and discovered that the fire had not reached his land, so he took the rugged access road to the yurt and collected some important items from inside: a laptop, some journals and documents, and two saxophones.

“The smoke was just billowing over the ridge one over from me,” he said, remembering the view from outside the yurt. He couldn’t see flames, but he could see the smoke spreading, indicating the fire was growing.

A sheriff, who was in radio contact with fire personnel, arrived and helped Gutierrez gauge how much time he had. For the next hour or so, Gutierrez and some friends filled up his 130 gallon water system and gathered other items, like tools and a bike, to carry back down.

Gutierrez remembers feeling unexpectedly calm while preparing for disaster. When the sheriff said it was time to leave, Gutierrez went back into the yurt to say goodbye, realizing it might be the last time he saw it. He looked over his shoulder from the doorway and saw the smoke advancing toward him, and felt sure the fire would soon follow.

He and his friends watched the fire and emergency responders from a safer spot along the loop road. Planes made laps around the fire, dropping retardant, but the smoke got bigger, the flames got brighter, and as evening fell, sheriff officers told spectators it was time to clear the loop road.

After noticing the piñon die-off in previous years, Gutierrez had started cutting down the dead ones close to the yurt, around 40 of them. He oriented the felled trunks along the contours of the slopes from which they grew and buried them into the hillsides. The practice serves three purposes: it removes the dry, dead trees from a position that would carry a fast, damaging crown fire; it creates berms that can help retain water and reduce erosion; and burying the wood creates an oxygen-free enclosure, making it difficult to ignite. The technique follows the permaculture principle of keeping all materials in a system within that system—a fourth outcome of the technique is that the nutrients from the wood eventually return to the soil.

“That was my first big COVID project,” Gutierrez said. “I spent weeks just cutting trees down with a handsaw or an axe.”

Even having done that work, Gutierrez knew when the fire began that there wasn’t a lot of “defensible space” around the yurt, which is surrounded by brush and trees.

“I knew if the fire was coming up to my zone, the yurt was toast, there’s no way that it could be saved,” said Gutierrez.

After later talking with firefighters, Gutierrez learned that defensible space isn’t only for the sake of the structure, but for the safety of the firefighters trying to protect it. He’s been more thorough in clearing trees and shrubs near the yurt since returning to it after an evacuation order for his area was lifted, even though some of those trees offer wind protection on the gusty ridge where the yurt stands.

After a restless night spent at a friend’s house Gutierrez went back to the loop road the next day and was surprised to see the yurt was untouched. With intense conditions and continuing fire growth, the next few days were a rollercoaster of worry and relief for Gutierrez, but eventually the evacuation order that applied to his property was lifted and he was able to check on the yurt. He found it unchanged, without even an odor of smoke—except for the view, which now includes a vast hillside of burned forest in the distance.

Gutierrez is luckier than several residents of Pack Creek who lost their homes or saw significant property damage. Property owners in the Dark Canyon and Holyoak areas are still under evacuation orders.

Gutierrez is grateful for that luck, and for generous community support. The Element hotel offered to house anyone displaced by the fire, and Gutierrez bonded there with others who had been evacuated from their homes and with the hotel staff, who, he said, showed exceptional hospitality and compassion.

“It makes me feel better about big new fancy hotels,” Gutierrez said. “It makes me realize there are good locals working at these places.”

The Element was also housing out-of-town firefighters assigned to the Pack Creek Fire, and talking with some of them raised Gutierrez’s optimism about the aftermath of the fire. He spoke with one crewmember from Colorado who had recently watched a beloved group of mountains burn outside his hometown—and afterwards, enjoyed watching the ecosystem revive, more quickly than he expected.

“He was talking about after the fire,” Gutierrez recalled, “and how cool and exciting and refreshing it was to explore. The thing that really stuck out to me was the look in his eyes, and the amazement and awe he had that he and his community were finding fulfillment and joy and resiliency.”

Gutierrez hopes that Moabites, who are deeply grieving for the mountains, will find similar unexpected joy in watching the La Sals regenerate.

“It’s not going to be a moonscape up there forever,” he said. “This is part of the whole natural cycle; these mountains have probably burned thousands of times on a long timeline.” He compared the forest to a family reunion: as time goes on, the older generation passes away, and a younger generation is born and develops.

“It’s painful to lose those elders, but it’s also part of life,” said Gutierrez. “There’s going to be a lot of grief—we have so many deep memories tied to these places.” He hopes that there will also be opportunities to discover new places, and to appreciate the renewal of the ecosystem.

For now Gutierrez is grateful for the strength of the Moab community and the relationships that have deepened as a result of the Pack Creek Fire, as well as for the firefighters who have achieved, as of June 30, 85% containment of the 8,952 acre Pack Creek Fire.

“They are heroes,” he said. “I have complete gratitude and awe for those people.”

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.