Some information may be outdated.

Public lands users will never agree on every issue.

But if they sit down and get to know each other, they can begin to build working relationships and potentially find common ground on the areas where they do see eye to eye.

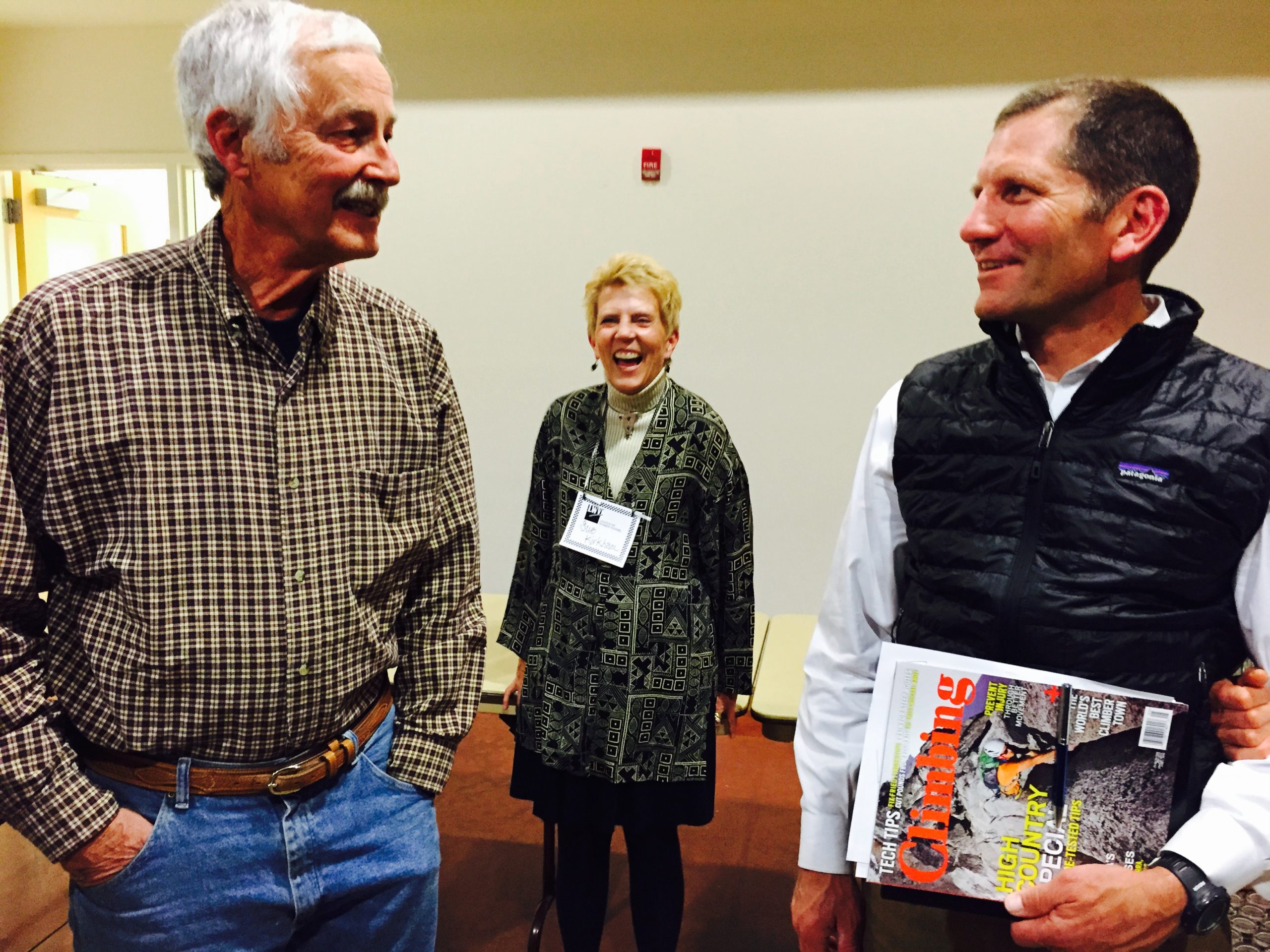

Take it from the four keynote speakers who addressed the Grand County League of Women Voters and 130 guests during a May 15 forum at the Grand Center: They reflected on their own experiences and other success stories in reaching consensus on sometimes-difficult issues.

The League of Women Voters organized the forum with the hope that it can move the discussion on public lands beyond the recent divisions in the community. Those disagreements centered around everything from Grand County’s brief involvement with a regional infrastructure development coalition, to a now-defunct proposal to build an “enhanced transportation corridor” through the Book Cliffs.

Sara Baldwin Auck, who directs the Interstate Renewable Energy Council’s regulatory program, urged audience members to get to know their elected officials, from the local level to the state and national political scenes.

In her case, Baldwin Auck has worked with state Rep. Mike Noel, R-Kanab, on clean energy policy.

Similar kinds of unlikely yet successful alliances are possible, she suggested, if citizens remain engaged in the policy-making process long beyond Election Day.

“That extends across the board to other senators and representatives, and council members and mayors,” she said. “It’s not enough to just show up and vote. It’s not enough to just show up to one single council meeting.”

Baldwin Auck recounted another experience where she worked on a legislative bill in support of energy efficiency that influential lobbyists had a hand in killing.

After her defeat, she wrote to the groups and asked them to help her understand their objections, with the hope that they could work together to find a solution they could both support.

“In going through that process, we addressed their concerns,” she said. “We added a few provisions, and what we got out of the deal was a new financing mechanism for commercial properties to access low-cost financing for energy-efficiency retrofits … that now the state Office of Energy Development is championing.”

When the bill finally passed, Baldwin Auck joined representatives from the bankers’ and builders’ associations arm in arm to say, “This is a great deal.”

“It can happen; it does happen,” she said.

In another instance, a diverse group of interests worked together to identify prime solar development zones on public lands in Utah that would have minimal impacts on wildlife and wildlife habitat. Those same zones now appear on official government maps that have streamlined the regulatory process for renewable energy developers, she said.

Closer to home, Public Land Solutions founder and director Ashley Korenblat touted Grand County Trail Mix as a local model that created a platform for citizens to shape the decisions that state and federal land management agencies make.

“There is this great opportunity to have a lot of say over what happens on your lands,” she said.

Brad Petersen, who heads Utah’s Office of Outdoor Recreation, encouraged stakeholders to make sure they have a clear sense of where someone with a differing viewpoint stands on an issue.

“You have to understand what their true feelings are and what they’re looking for,” he said.

One of the most legendary figures in Moab’s history had the ability to do just that.

Former Arches and Canyonlands National Park Superintendent Bates Wilson was a master in building bridges on public lands issues, due in no small part to the power of his personality.

Author Jen Jackson Quintano, who wrote the acclaimed biography “Blow Sand in His Soul: Bates Wilson, the Heart of Canyonlands,” described Wilson as a man of contradictions: He grew up on a ranch in New Mexico, yet he attended an elite prep school in New Jersey.

Throughout his life, he transitioned seamlessly between different social worlds and classes, and he respected people and the natural environment alike.

“He fell in love with the canyons and the characters,” she said.

Utah’s governor at the time opposed efforts to create Canyonlands National Park, suggesting that society might need to make use of the Needles District’s stone pillars for building materials some day.

“Yet Bates still got his park,” Jackson Quintano said, recalling his experiences building support for the idea – often by reaching out to one influential person at a time.

Over the years, Wilson’s legacy grew to the point that the Utah Legislature passed a memorial resolution in his honor after his death.

Korenblat said that public lands stakeholders can forge alliances based on shared values, instead of focusing on individual group mission statements and values.

When they choose the latter approach, she said, they build boxes around themselves.

Baldwin Auck said those boxes do not allow people to see issues from different perspectives.

“I challenge you all to look at your own boxes,” she said. “Don’t be a cave person.”

A cave person could refer to someone who spends his or her time in the dark, although Baldwin Auck used it as an acronym that stands for “Citizens Against Virtually Everything.”

Korenblat ultimately reminded everyone in the audience that no matter how they feel about a particular issue, they all have a shared love of the surrounding landscape.

“Many of us could live anywhere,” she said. “We chose this place.”

Grand County League of Women Voters member Barbara Browning echoed those comments.

“All of us love this land, and there are ways that we can and should and will come together and discuss the possibilities,” she said.

As the forum drew to a close, Browning said she hopes that it will be just the first chapter of an ongoing dialogue in the community.

“Let’s do this again,” she said. “This can’t just be a one-time thing.”

League of Women Voters forum guests share success stories

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep local news alive.

Chip in to support the Moab Sun News.