Grand County is officially a safe haven for wild and feral honey bees.

The Grand County Council voted unanimously on Tuesday, June 2, to pass one of the country’s first ordinances designed to curb the spread of diseases and other stresses by limiting commercial migratory beekeeping activities. Under the ordinance, large-scale, traveling beekeepers are prohibited from operating in Grand County south of Interstate 70, and all the way to the San Juan County line.

Council member Rory Paxman was not present for the vote, but Grand County Council chair Elizabeth Tubbs said that he fully supports the measure.

“I think he told us that he does have a couple of hives,” she noted.

The council passed the ordinance with minimal discussion, following a low-key public comment period on the proposal.

“I think that the council was all in favor of keeping our bee population as healthy as possible, without having a non-localized population in here and potentially bringing in diseases or other problems,” Tubbs said. “Our population is very healthy and unique, and we want to keep it that way.”

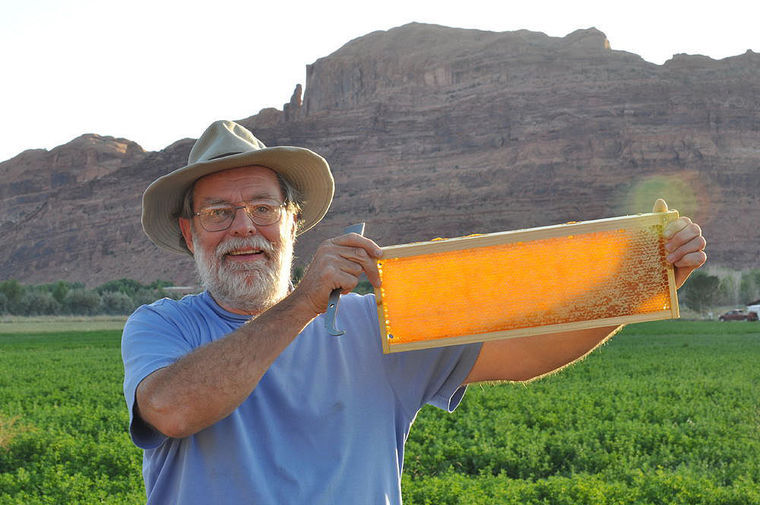

It’s a different story across much of the country, where beekeeping operations are fraught with problems, according to Grand County Honey Bee Inspector Jerry Shue.

There are half as many managed honey bee colonies in the U.S. today as there were in the 1940s, even though demand for pollinator services is constantly on the rise, since bees are essential to the production of almonds and many other crops.

No single factor can be blamed for the nationwide drop in honey bee populations, which are linked to a complex array of factors, including parasitic mites, disease, household pesticide use, and agricultural and residential development.

“It’s a multitude of issues that are causing bee health problems,” Shue told the county council last month.

A bacterial disease called American foulbrood is one of the most concerning problems out there, but according to Shue, it’s one problem that Moab-area beekeepers don’t have to contend with.

The town’s relative isolation, along with its smaller-scale agricultural development, could be serving as natural and artificial barriers to diseases and parasites that decimate bee populations elsewhere.

“It’s largely geographic; it’s partly economic,” Shue said. “We don’t have a need for big migratory pollinating operations, so I think we’re lucky.”

Migratory beekeepers disrupt the insects’ natural life cycles, he said, by waking them up in the dead of winter. To get them going, they pump them up with high-fructose corn syrup, antibiotics and synthetic pollen.

Eventually, they proceed to ship them off in extremely tight quarters: A single tractor-trailer load may contain as many as 400 colonies. Commercial populations then travel from place to place, where they’re potentially exposed to unhealthy conditions.

“It’s like sending all of your kids to day care, and they pick up what the kid who’s just been to New York City has,” Shue said.

According to Shue, the nearest commercial beekeeping operations are in the town of Green River and Grand Junction, Colorado. Draw a 50-mile radius around a map of the Moab area, however, and Shue will point out that only wild and feral bee populations live inside it.

“And within that circle, we are unto ourselves,” he said.

Shue decided to pursue the ordinance after he read a local newspaper ad that a Wyoming man placed for a part-time seasonal helper. According to Shue, the man wanted to winter his migratory bees in milder Grand County in order to cut down on his seasonal feeding costs.

The man’s proposal never went anywhere, but Shue feared that any bees the man brought to the area would intermix with local bee populations, potentially exposing them to viruses and diseases.

“That’s what scared me,” he said.

Shue assured the county council last month that it isn’t stepping on any toes by adopting the ordinance to restrict such operations.

Local agricultural areas are nothing like California’s vast agricultural lands, he said, where bee-dependent almond growers pollinate orchards that spread out for miles in all directions.

“There’s nobody in Grand County interested in doing that,” he said.

What the county does have, he said, is like-minded beekeepers who want to raise healthy populations of bees, without the use of antibiotics.

At last count, there were about 41 beekeepers and around 120 hives in the county, including a couple of hives at the U.S Department of Energy’s Moab Uranium Mill Tailings Remedial Action (UMTRA) Project site.

“There’s a groundswell of interest in beekeeping,” he said.

Moab beekeepers Tim Walsh and Roy Vaughn tend to several of those hives off 500 West that are home to hardy Russian bees.

They hoped to split them up into “baby colonies” that others could use for their own hives.

“We were going to make smaller hives available to aspiring beekeepers,” Walsh said.

Unfortunately, their bees had a rough winter, despite the milder-than-average temperatures.

To stay warm, the bees rotate around in balls, and as their numbers dwindled, Walsh said the hives suffered.

“By splitting them up, we didn’t have a critical mass,” he said.

However, their latest project should be a boon to bees far beyond their hives: They worked with local landowner Ray Alger to plant a pollinator-friendly legume on a full acre of nearby land. (Please see related story in this week’s Moab Sun News.)

Overall, populations of wild and feral honey bees in Grand and San Juan counties seem to be resilient, with estimated losses of 15 to 20 percent last year, according to Shue.

“The norm for the nation is that most wild honey bees have died out,” he said.

During a trip down to the Navajo Nation, Shue and others found a colony of bees inside a camper trailer.

“We took them out of there and got very nice honey from something out in the middle of the desert,” he said.

They later traced those bees to a genetic strain that came from the Middle East about 120 years ago. Surprisingly, they found that strain does not exist in commercial populations elsewhere in the U.S.

“We have genetic reservoir here,” he said.

Not to alarm anyone, but Shue also found two colonies of Africanized bees – which some media outlets dub “killer bees” due to their feistiness – along the Green River in Grand County.

Researchers previously confirmed that the species reached the Bluff area several years ago, although the new colonies did come as a surprise to one expert in the field, according to Shue.

“I had one professor say he was pretty surprised to find Africanized bees at 4,000 feet (above sea level),” he said. “It’s one of the higher elevations and further north than they were expected to be.”

However, none of those Africanized bees have caused any problems whatsoever.

“And so the last thing we should perceive is that it’s some kind of invasion or threat or an emergency,” Shue said.

“The very best thing we can do in this kind of situation is monitor it to find out where are wild bees are and where they’re coming from (and) have them tested,” he added. “Having healthy, managed bees by beekeepers is one of the best defenses, because that dilutes any influence (the Africanized bees) might have.”

New ordinance aims to promote health of local honey bee populations

Our (bee) population is very healthy and unique, and we want to keep it that way.