The Bureau of Reclamation should be abolished and Glen Canyon Dam should be torn down, former agency head Daniel P. Beard says in his new book, “Deadbeat Dams.”

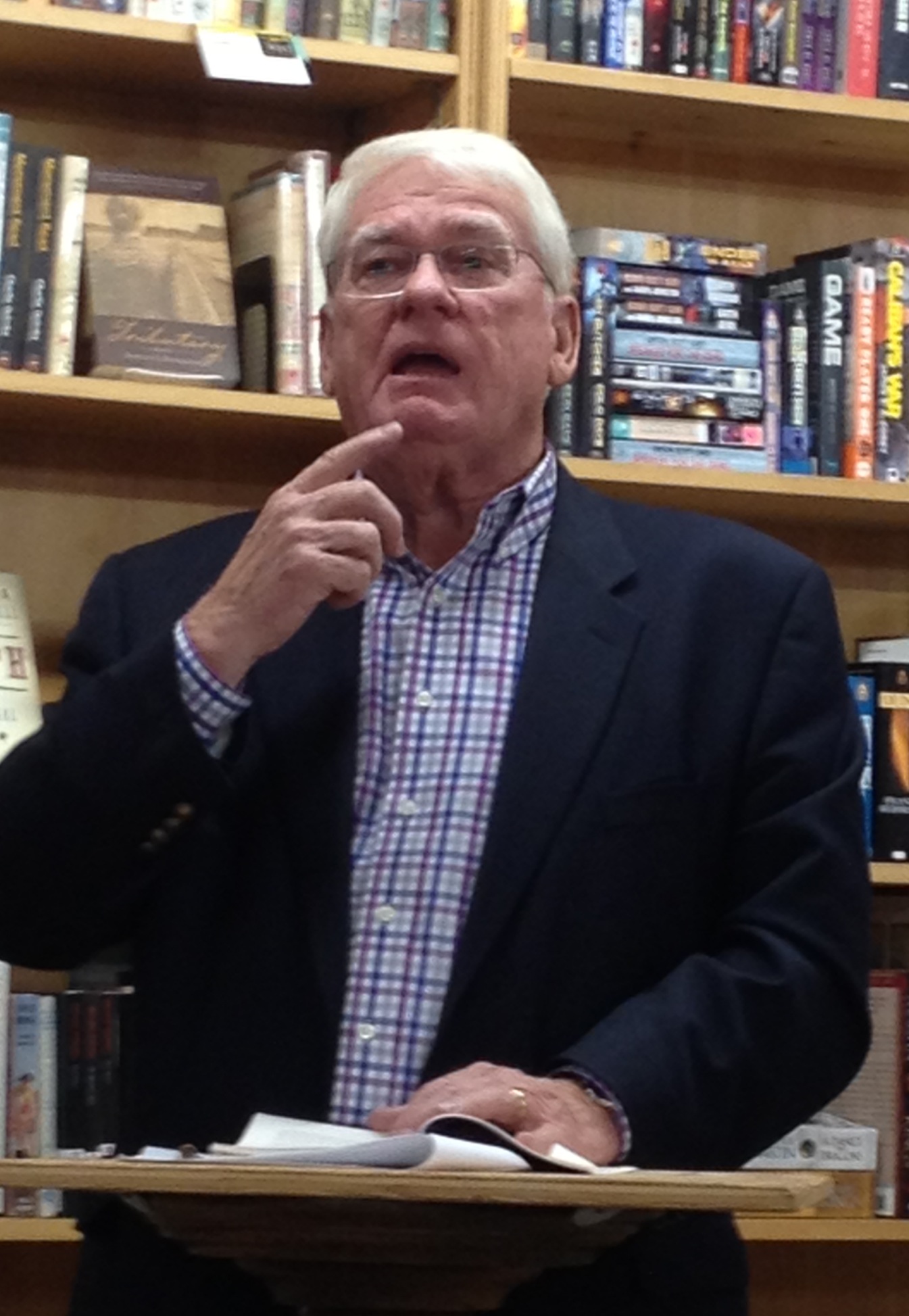

Beard discussed his book on Thursday, April 2 at Back of Beyond Books with a crowd of around 50. He told the audience that the bureau was an outdated, ineffective and hugely inefficient agency beholden to special interests at the expense of billions of dollars to the taxpayer. He referred to the agency as “deadbeat.”

“A deadbeat is someone who avoids paying their bills,” Beard said. “They are a loafer and a sponge who wring other people dry.”

He said the agency was ill-prepared to manage water through the current drought, and that construction of Glen Canyon Dam was a misguided political decision based on false assumptions about the availability of Colorado River water in a dynamic climate.

“It was an historic blunder of monumental proportions,” he said.

Glen Canyon Dam was authorized as part of the Colorado River Storage Project Act and construction was completed in 1963. It was hailed as a monumental achievement and its purpose was said to be threefold: flood control, water storage as a hedge against drought and the generation of hydroelectric power, the sale of which was supposed to help finance other water projects in the West.

The project faced little opposition at the time. But Glen Canyon Dam has since become the bane of environmentalists, who say the flooding of Glen Canyon by Lake Powell was one of the greatest environmental tragedies of all time.

The 200-mile-plus-long canyon was a scenic wonder rich with riparian life, twisting tributary canyons, natural arches and hundreds of archaeological sites from the Anasazi and Fremont cultures.

Beard said that just because politicians made poor decisions in the past doesn’t mean that society is bound to live with them indefinitely. He cited more than 1,100 dam removal projects currently in place in the U.S. He said that dams are being removed for a variety of reasons, including the restoration of native salmon fisheries, deterioration, or that they have simply outlived their usefulness.

“We all make mistakes and we all understand that an object can become obsolete,” Beard said. “Times and conditions change.”

Beard also said that policy decisions surrounding the use and effectiveness of Glen Canyon Dam need to take into account the “elephant in the room” of climate change.

“We’re in the middle of a megadrought, the worst in 1,000 years.” Beard said. “There is growing scientific evidence that the entire premise on which we’ve built our water supply system is undergoing radical change.”

U.S. Bureau of Reclamation spokesperson Mathew Allen told the Moab Sun News that Lake Powell has been “one of the heroes of the current drought.”

“The past 15 years are the driest in the historical record which dates back over a century,” Allen said. “Even now, during one of the driest periods in recorded history, the value of Glen Canyon Dam and power plant cannot be understated.”

Allen said that Lake Powell, when full, holds a two-year supply of the Colorado River’s average flow, and that this has significantly reduced the impact of current drought conditions.

“More than 30 million people rely on water from the Colorado River Storage Project of which, Glen Canyon Dam is the cornerstone feature,” he said. “Additionally, nearly 5.8 million people are provided clean, renewable power from the Glen Canyon power plant.”

Beard said that there is no longer any surplus water available in Lake Powell to provide for drought, and that the year 2000 was a tipping point in which demand on the Colorado River exceeded supply. He said that it is unlikely that Lake Powell will ever be filled again.

Lake Powell, and Lake Mead further downstream, are currently at 45 percent of capacity as the region moves into its 16th year of drought. As of April 1, the upper Colorado River Basin snowpack was at 69 percent of normal, and bureau officials predict that even after the spring run off, Lake Powell will drop to at least 44 percent capacity or less.

Beard advocates draining Lake Powell and filling Lake Mead downstream. He said that would save an enormous amount of water in the long run due to the huge amounts that are lost to evaporation off the surface of Lake Powell, and through seepage into the porous Navajo Sandstone. He said that under current conditions, both reservoirs are in danger of dropping below the level necessary to produce power.

Allen said that there is a low probability that Lake Powell will reach levels where power production won’t be possible.

“There is very little to no risk that we are going to reach this point in the next decade,” he said. “It’s not a gloom and doom scenario by any means.”

Living Rivers Executive Director John Weisheit said that even though the reservoir is at 45 percent capacity, power production stops at 20 percent.

“That means the reservoir has only 25 percent of usable capacity,” he said. “The glass is way more than half empty.”

Allen said that the bureau is in a unique management position in that it can’t create the supply, nor can it dictate a “be all end all” policy. He said the bureau is taking a “collaborative adaptive management approach” to work with various stakeholders including Native American tribes, states and federal partners to develop “interim guidelines” in the event of extended drought or impacts from climate change.

“When you are dealing with policy at that level, one agency can’t make the decision,” Allen said. “It takes a collaborative approach.”

Beard said that serious reforms are needed, and that our water needs can be met through “conservation, efficiency and reuse,” but that the political will is lacking to make the necessary changes.

“Politics is at the heart of every Western water decision,” he said. “We need to encourage solutions to water problems using innovative, low-cost solutions that promote conservation and more efficient use of water.”

Daniel P. Beard spoke during Moab visit; Current Reclamation officials say Lake Powell is more important than ever

It was an historic blunder of monumental proportions