In the coming months many of the abandoned uranium mines in Grand County, and across America, will be identified, reviewed and categorized by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE).

The directive for the Abandoned Uranium Mines Report to Congress comes as part of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2013.

The act directs the DOE’s Office of Legacy Management to work in conjunction with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) in compiling the report.

“The report is to identify abandoned uranium mines that provided uranium ore for the Atomic Energy Defense Act activities. It’s not to try to identify every abandoned uranium mine,” said Ray Plieness, a senior advisor for Legacy Management.

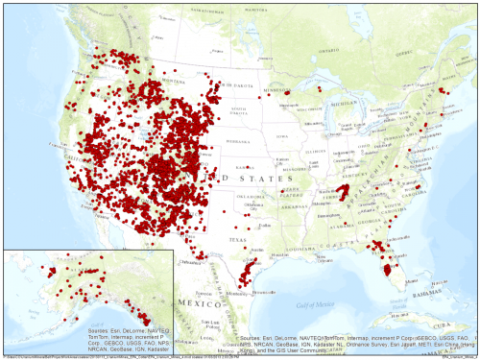

There are thousands of abandoned uranium mines across the western U.S. on federal, state, private and tribal lands. The early uranium mines were permitted until about 1971 by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, the predecessor to the DOE, said Sarah Fields, the director of Uranium Watch, a Moab-based non-profit that works to educate the public on uranium mining issues and to advocate remediation and safe mining practices.

“The Atomic Energy Commission was more interested in making sure they had a steady supply of ore,” Fields said. “There were no requirements for a plan of operations or reclamation.”

Though these mines were permitted across the country, the majority of the ore came from mines in the Four Corners region, with over 250 abandoned uranium mines in Utah’s Grand, Emery and San Juan counties alone. Fields believes that these abandoned mines are a danger to human and environmental health.

“It’s hazardous to have open portals and shafts. It’s hazardous to have high levels of radiation, especially when we have a desert climate and dust is blown around and spread throughout the community,” she said.

Fields also noted that there is the issue of both grazing and wild animals being exposed to radiation through drinking from old uranium mine holding ponds.

Many of the abandoned mines that supplied ore for the Atomic Energy Defense Act are located on tribal land. The communities and government programs in these areas have been struggling to deal with the environmental and public health consequences caused by these mines, said Nicole Moutoux, a Navajo Nation abandoned uranium mine coordinator for the EPA.

“(There has been a) huge impact for every community near a mining area. The abandoned mine areas are wide spread across the entire nation,” she said. “Health effects can range from cancer to neurological issues when you have high or chronic exposure. The lasting impacts are that these mine areas are just out there and abandoned and sometimes people will build homes on top of them or take materials from them to build their homes.”

Moutoux believes that the EPA’s work with abandoned uranium mines, along with that of other organizations, may have led congress to request the Abandoned Uranium Mines report.

The Abandoned Uranium Mine report was introduced into the National Defense Authorization Act by Senator Mark Udall (D), from Colorado.

Colorado is home to approximately 1,300 of the uranium mines that were used to produce ore for nuclear weapons, according to the senator’s website.

The DOE, DOI and EPA will be working with state, local and tribal agencies, as well as organizations like Uranium Watch, to locate the mines. The report will also rank the danger posed by each mine, its priority level for remediation, the potential cost of that remediation, and the status of any efforts to remediate or reclaim the mines.

“We will try to analyze the risks and different factors, like the proximity to populations and the availability of a receptor (for ore), and what can we do for a certain amount of cost,” Plieness said.

One of the primary challenges will be to find all of the mines. As it stands there is no centralized database of abandoned uranium mines in many of the effected states.

In Utah different agencies, including the Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management, and the Utah Division of Oil, Gas and Mining, all have there own lists. However, there is doubt as to how comprehensive any of them are, as there was very little oversight during that time, Fields said.

“Rules and regulation and oversight were limited back then,” agreed Plieness. “A lot of these were Mom and Pop operations. When the economy of the uranium industry dropped off, they walked away.”

There are currently around 4,100 known abandoned uranium mines across the country that fall under the purview of the Abandoned Uranium Mine report, but Plieness expects that number to grow.

In order to inform the public and get public input, Legacy Management is in the process of holding five public, stakeholders forums around the country for interested individuals. The first forum was March 27 and 28 in Salt Lake City.

The Abandoned Uranium Mine report is to be delivered to Congress by July 2014.

Though identifying and appraising these mines will be a step in the right direction, Fields believes that there is still a great deal more that needs to be done.

“The DOE would assess one subset of (abandoned uranium) mines, and then they would have to get funding for the clean up,” she said. “They need funding for the clean up program. They need a full assessment for all the uranium mines.”

Several agencies in Utah have done work to remediate abandoned uranium mines, but a dearth of funding has meant that there are still many abandoned mines in need of reclamation.

One of the difficulties, said Fields, has been that once agencies get beyond removing hazards like sink holes or open shafts, costly assessments are needed to determine the next step in addressing issues like radiation.

“There needs to be federal assistance for cleaning up the mines. This should not take an additional 40 or 50 years, on top of the decades it has already taken, to address,” Fields said. “(The Abandoned Uranium Mine report) should be a stepping stone for federal funding for clean up projects not just in Utah but in states throughout the west. And it would provide jobs, that’s for sure.”